The Outdoor Girls at Bluff Point, by Laura Lee Hope

CONTENTS

| chapter | page | |

| I | To the Front | 1 |

| II | Bad News | 11 |

| III | Making Plans | 17 |

| IV | Grace Surprises Her Chums | 27 |

| V | A Problem Solved | 37 |

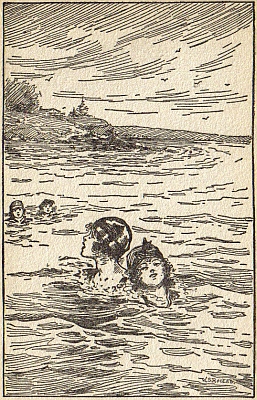

| VI | Life and Death | 47 |

| VII | The Race | 56 |

| VIII | Red Rags | 65 |

| IX | Thunder and Mud | 75 |

| X | The Knight of the Wayside | 85 |

| XI | Mystery | 95 |

| XII | Nearly an Accident | 104 |

| XIII | Outwitting a Crank | 114 |

| XIV | Bluff Point at Last | 123 |

| XV | The Telegram | 132 |

| XVI | The Shadow of Disaster | 142 |

| XVII | Joe Barnes Again | 152 |

| XVIII | Seriously Wounded | 162 |

| XIX | Betty Confesses | 170 |

| XX | Missing | 180 |

| XXI | A Narrow Escape | 187 |

| XXII | Darkness Before the Dawn | 197 |

| XXIII | The Shadow Lifts | 207 |

| XXIV | His Three Sweethearts | 217 |

| XXV | Joy | 227 |

THE OUTDOOR GIRLS

AT BLUFF POINT

CHAPTER I

TO THE FRONT

“I know it’s utterly foolish and unreasonable,” sighed Amy Blackford, laying down the novel she had been reading and looking wistfully out of the window, “but I simply can’t help it.”

“I know it’s utterly foolish and unreasonable,” sighed Amy Blackford, laying down the novel she had been reading and looking wistfully out of the window, “but I simply can’t help it.”

“What’s the matter?” asked Mollie Billette, raising her eyes reluctantly from a book she was devouring and looking vaguely at Amy’s profile. “Did you say something?”

“What’s the matter?” asked Mollie Billette, raising her eyes reluctantly from a book she was devouring and looking vaguely at Amy’s profile. “Did you say something?”

“No, she only spoke,” drawled Grace Ford, extricating herself from a mass of bright colored cushions on the divan, preparatory to joining in the conversation. “I ask you, Mollie, did you ever know Amy to say anything important?”

“No, she only spoke,” drawled Grace Ford, extricating herself from a mass of bright colored cushions on the divan, preparatory to joining in the conversation. “I ask you, Mollie, did you ever know Amy to say anything important?”

“Why yes, I have,” said Mollie unexpectedly. “In fact, she is about the only one of us Outdoor Girls who ever does say anything important—except Betty, perhaps.” [2]

“Why yes, I have,” said Mollie unexpectedly. “In fact, she is about the only one of us Outdoor Girls who ever does say anything important—except Betty, perhaps.” [2]

Amy withdrew her gaze from the landscape and looked at the speaker with a twinkle in her eyes.

Amy withdrew her gaze from the landscape and looked at the speaker with a twinkle in her eyes.

“What will you have, Mollie?” she asked whimsically. “When you become complimentary, you are apt to rouse my suspicions.”

“What will you have, Mollie?” she asked whimsically. “When you become complimentary, you are apt to rouse my suspicions.”

“Well, whatever you were going to say, please say it, and let me get back to my book,” returned Mollie, ignoring the imputation. “I was in the most interesting part—”

“Well, whatever you were going to say, please say it, and let me get back to my book,” returned Mollie, ignoring the imputation. “I was in the most interesting part—”

“Why, I’m just plain homesick,” said Amy, adding quickly, as the girls looked at her in surprise. “For Camp Liberty and the Hostess House, you know. I miss the work and the long hours of entertaining and cheering people up. I feel,” she looked around at them as though finding it hard to explain just what she meant, “sort of—lost.”

“Why, I’m just plain homesick,” said Amy, adding quickly, as the girls looked at her in surprise. “For Camp Liberty and the Hostess House, you know. I miss the work and the long hours of entertaining and cheering people up. I feel,” she looked around at them as though finding it hard to explain just what she meant, “sort of—lost.”

The three chums, Mollie Billette, Grace Ford, and Amy Blackford were gathered in the comfortable library of Betty Nelson’s home—Betty being the fourth of the merry quartette, dubbed the “Outdoor Girls” by the people of Deepdale, because of their love of the open and of outdoor sports.

The three chums, Mollie Billette, Grace Ford, and Amy Blackford were gathered in the comfortable library of Betty Nelson’s home—Betty being the fourth of the merry quartette, dubbed the “Outdoor Girls” by the people of Deepdale, because of their love of the open and of outdoor sports.

The girls, as my old readers will doubtless remember, had helped establish a Hostess House at Camp Liberty, and since then had given all their strength and time and youthful enthusiasm to the great work of cheering our young fighters, entertaining their loved ones, and, in the end, sending them with fresh courage and happy memories to the “other side” for the great adventure.

The girls, as my old readers will doubtless remember, had helped establish a Hostess House at Camp Liberty, and since then had given all their strength and time and youthful enthusiasm to the great work of cheering our young fighters, entertaining their loved ones, and, in the end, sending them with fresh courage and happy memories to the “other side” for the great adventure.

And now the girls, completely worn out in their loving service to others, had been sent, much against their will, home to Deepdale for a rest that they sorely needed.

And now the girls, completely worn out in their loving service to others, had been sent, much against their will, home to Deepdale for a rest that they sorely needed.

To-day they had gathered in Betty’s house to discuss the rather hazy plans for their brief vacation. And Amy had simply voiced what was in the thoughts of all the girls. They were, undeniably and heartily, homesick for Camp Liberty and their work at the Hostess House.

To-day they had gathered in Betty’s house to discuss the rather hazy plans for their brief vacation. And Amy had simply voiced what was in the thoughts of all the girls. They were, undeniably and heartily, homesick for Camp Liberty and their work at the Hostess House.

“Lost?” Mollie repeated Amy’s expression thoughtfully. “Yes, I guess that would pretty well describe the feeling I’ve had for the last few days. Sort of restless and aimless—wondering what to do next.”

“Lost?” Mollie repeated Amy’s expression thoughtfully. “Yes, I guess that would pretty well describe the feeling I’ve had for the last few days. Sort of restless and aimless—wondering what to do next.”

“Goodness!” cried Grace whimsically, stretching her arms above her head and smothering a yawn, “this is terrible, you know. If we don’t look out, we’ll be forgetting how to enjoy ourselves.”

“Goodness!” cried Grace whimsically, stretching her arms above her head and smothering a yawn, “this is terrible, you know. If we don’t look out, we’ll be forgetting how to enjoy ourselves.”

“That would be queer, wouldn’t it?” agreed Mollie, with a chuckle as she started to resume her reading. “Especially for the Outdoor Girls, who used to know how to enjoy themselves remarkably well.”

“That would be queer, wouldn’t it?” agreed Mollie, with a chuckle as she started to resume her reading. “Especially for the Outdoor Girls, who used to know how to enjoy themselves remarkably well.”

A brief silence followed, broken only by the rustle of paper as one of the girls turned a page. Then, so suddenly that Mollie jumped nervously and Grace almost upset a box of chocolates at her elbow, Amy threw down her book and sprang to her feet.

A brief silence followed, broken only by the rustle of paper as one of the girls turned a page. Then, so suddenly that Mollie jumped nervously and Grace almost upset a box of chocolates at her elbow, Amy threw down her book and sprang to her feet.

“I can’t stand it another minute!” she exclaimed desperately. “Girls, I must get out and do something—this loafing is getting on my nerves.”

“I can’t stand it another minute!” she exclaimed desperately. “Girls, I must get out and do something—this loafing is getting on my nerves.”

“Goodness, the child’s mad,” declared Mollie, looking at her chum with a mixture of amusement and sympathy in her eyes. “What do you want to do, Amy, start a fight, or set the town on fire? Whatever it is, I’m for you, as Roy would say.”

“Goodness, the child’s mad,” declared Mollie, looking at her chum with a mixture of amusement and sympathy in her eyes. “What do you want to do, Amy, start a fight, or set the town on fire? Whatever it is, I’m for you, as Roy would say.”

“Oh, I guess I must be crazy,” said Amy, subsiding and seeming a little ashamed of her outburst. “Only, after so much band music and parades and bugle calls—everything in Deepdale seems so quiet.”

“Oh, I guess I must be crazy,” said Amy, subsiding and seeming a little ashamed of her outburst. “Only, after so much band music and parades and bugle calls—everything in Deepdale seems so quiet.”

“Well, if all you want is noise, we’ll easily fix that,” said Mollie briskly, running to the piano and gathering in Grace and Amy on the way. “Sing,” she commanded, “and I’ll make as much noise as I can on the piano. “[5]

“Well, if all you want is noise, we’ll easily fix that,” said Mollie briskly, running to the piano and gathering in Grace and Amy on the way. “Sing,” she commanded, “and I’ll make as much noise as I can on the piano. “[5]

Half laughing, half protesting, the girls obeyed while Mollie conscientiously made good her threat with the piano, and it was into this uproar that Betty Nelson stepped a moment later.

Half laughing, half protesting, the girls obeyed while Mollie conscientiously made good her threat with the piano, and it was into this uproar that Betty Nelson stepped a moment later.

“Have mercy!” she screamed above the noise, both hands clapped over her ears while she laughed at them. “I thought they had turned the house into a lunatic asylum or something.”

“Have mercy!” she screamed above the noise, both hands clapped over her ears while she laughed at them. “I thought they had turned the house into a lunatic asylum or something.”

The music, if such it can be called, stopped so suddenly that Betty’s last words rang out with absurd distinctness.

The music, if such it can be called, stopped so suddenly that Betty’s last words rang out with absurd distinctness.

“Or something,” Mollie mimicked, whirling around and catching the newcomer in a bear’s embrace. “Come over to the couch, Betty Nelson, and explain yourself. Where have you been and why did you keep us waiting?”

“Or something,” Mollie mimicked, whirling around and catching the newcomer in a bear’s embrace. “Come over to the couch, Betty Nelson, and explain yourself. Where have you been and why did you keep us waiting?”

Laughingly the Little Captain, as she was often called by the girls because of her talent for leadership, permitted herself to be dragged over to the couch by the impulsive Mollie, while Amy and Grace seated themselves on the arms.

Laughingly the Little Captain, as she was often called by the girls because of her talent for leadership, permitted herself to be dragged over to the couch by the impulsive Mollie, while Amy and Grace seated themselves on the arms.

“What would you?” protested Betty, looking from one accusing face to another. “I said I would meet you here at two-thirty, and it is only quarter past now.”

“What would you?” protested Betty, looking from one accusing face to another. “I said I would meet you here at two-thirty, and it is only quarter past now.”

“Only quarter past!” exclaimed Amy.

“Only quarter past!” exclaimed Amy.

“Oh, is that all?” asked Mollie, in astonishment, adding, as Betty lifted her wrist watch for[6] inspection: “Goodness, I thought we had been waiting ages.”

“Oh, is that all?” asked Mollie, in astonishment, adding, as Betty lifted her wrist watch for[6] inspection: “Goodness, I thought we had been waiting ages.”

“I’m glad you wanted to see me so much,” chuckled the Little Captain, adding, with a mischievous twinkle in her eyes: “I imagine you would have been still more impatient if you had known—” she paused wickedly and just looked at them.

“I’m glad you wanted to see me so much,” chuckled the Little Captain, adding, with a mischievous twinkle in her eyes: “I imagine you would have been still more impatient if you had known—” she paused wickedly and just looked at them.

“Don’t tease, Betty! What is it?” they implored in chorus, fairly pouncing upon her, while Grace added, eagerly:

“Don’t tease, Betty! What is it?” they implored in chorus, fairly pouncing upon her, while Grace added, eagerly:

“Is it possible you have anything really interesting to tell us?”

“Is it possible you have anything really interesting to tell us?”

“I shouldn’t wonder if you would think so,” Betty teased, adding quickly to forestall the outburst she saw was coming, “It really isn’t anything at all—only—I met the postman on my way—”

“I shouldn’t wonder if you would think so,” Betty teased, adding quickly to forestall the outburst she saw was coming, “It really isn’t anything at all—only—I met the postman on my way—”

“Betty!” they cried, unable to contain their impatience another moment. “You have letters! Letters from our soldier boys!”

“Betty!” they cried, unable to contain their impatience another moment. “You have letters! Letters from our soldier boys!”

“How did you guess it?” said Betty, her eyes dancing as she brought from a convenient pocket three—yes, three—fat letters, each containing the longed-for foreign postmark.

“How did you guess it?” said Betty, her eyes dancing as she brought from a convenient pocket three—yes, three—fat letters, each containing the longed-for foreign postmark.

“How much will you give me?” teased Betty, holding the precious missives behind her back.

“How much will you give me?” teased Betty, holding the precious missives behind her back.

“Not one other word, Betty Nelson!” they cried, and after a merry but brief struggle the letters were seized and delivered to their rightful owners.

“Not one other word, Betty Nelson!” they cried, and after a merry but brief struggle the letters were seized and delivered to their rightful owners.

“Now I wonder,” drawled Grace with a twinkle, as she hastily tore open her envelope, “who could possibly be writing to us from the other side?”

“Now I wonder,” drawled Grace with a twinkle, as she hastily tore open her envelope, “who could possibly be writing to us from the other side?”

“Now I wonder,” chuckled Betty, as she happily drew from the convenient pocket the last, but in her estimation decidedly not the least, fat letter and proceeded to devour its contents without delay.

“Now I wonder,” chuckled Betty, as she happily drew from the convenient pocket the last, but in her estimation decidedly not the least, fat letter and proceeded to devour its contents without delay.

And indeed the Outdoor Girls had little reason to wonder who their correspondents might be, for as regularly as clockwork those precious letters with the strange foreign postmarks were delivered to their eager hands.

And indeed the Outdoor Girls had little reason to wonder who their correspondents might be, for as regularly as clockwork those precious letters with the strange foreign postmarks were delivered to their eager hands.

There were other letters with that foreign postmark, too, for in addition to their work at the Hostess House, the girls had faithfully kept up a large correspondence with the brave boys who had already crossed the water and were waiting impatiently for their chance “at the Huns.”

There were other letters with that foreign postmark, too, for in addition to their work at the Hostess House, the girls had faithfully kept up a large correspondence with the brave boys who had already crossed the water and were waiting impatiently for their chance “at the Huns.”

But the four special letters were from their closest friends—boys who had lived in Deepdale before the war and were now in France preparing for the last stage of their journey.

But the four special letters were from their closest friends—boys who had lived in Deepdale before the war and were now in France preparing for the last stage of their journey.

Allen Washburn, on his way to make a great name for himself in the law before the war put a temporary check upon his ambitions, had been in love with the Little Captain for—oh, yes, ever since he could remember, while Betty—but Betty would never really admit anything, not even to herself.

Allen Washburn, on his way to make a great name for himself in the law before the war put a temporary check upon his ambitions, had been in love with the Little Captain for—oh, yes, ever since he could remember, while Betty—but Betty would never really admit anything, not even to herself.

Then there was Will Ford, Grace Ford’s brother, who was not only devoted to his pretty sister, but, in spite of Amy’s flushed protestations to the contrary, to Amy Blackford, also—although in quite a different manner!

Then there was Will Ford, Grace Ford’s brother, who was not only devoted to his pretty sister, but, in spite of Amy’s flushed protestations to the contrary, to Amy Blackford, also—although in quite a different manner!

Frank Haley was a high school chum of Will’s, who from the time of his first meeting with Mollie Billette had seemed inclined to become her shadow, to the latter’s secret gratification and outward indifference.

Frank Haley was a high school chum of Will’s, who from the time of his first meeting with Mollie Billette had seemed inclined to become her shadow, to the latter’s secret gratification and outward indifference.

The last of the quartette was Roy Anderson, one of the Deepdale boys, who was chiefly distinguished by his very open admiration for Grace.

The last of the quartette was Roy Anderson, one of the Deepdale boys, who was chiefly distinguished by his very open admiration for Grace.

The boys had shared in many of the adventures of the Outdoor Girls, and of course had been among the very first to volunteer to help “lick the Boche” as they slangily but ardently put it. The girls had gloried in their patriotism, and it was their assignment to Camp Liberty that had first given Betty the idea of working in the Hostess House there.

The boys had shared in many of the adventures of the Outdoor Girls, and of course had been among the very first to volunteer to help “lick the Boche” as they slangily but ardently put it. The girls had gloried in their patriotism, and it was their assignment to Camp Liberty that had first given Betty the idea of working in the Hostess House there.

They had been very happy, fired as they were by enthusiastic patriotism, until the fateful day[9] had come when the boys had entrained for Philadelphia and from there to the Great Adventure. Then for the first time the girls had had the real and terrible meaning of war brought home to them. And the boys, so merry and care-free when they had first entered the service, had seemed suddenly older, more important, more manly, only the fire of enthusiasm in their eyes showing their indomitable youth.

They had been very happy, fired as they were by enthusiastic patriotism, until the fateful day[9] had come when the boys had entrained for Philadelphia and from there to the Great Adventure. Then for the first time the girls had had the real and terrible meaning of war brought home to them. And the boys, so merry and care-free when they had first entered the service, had seemed suddenly older, more important, more manly, only the fire of enthusiasm in their eyes showing their indomitable youth.

Several months had passed since that day of mingled tears and pride and heartache, and the girls had had time to get used to the separation a little—a very little. And now Betty had brought them the letters they were always hungry for, anxiously eager, yet always, at the very back of their hearts, a little haunting fear of what they might contain.

Several months had passed since that day of mingled tears and pride and heartache, and the girls had had time to get used to the separation a little—a very little. And now Betty had brought them the letters they were always hungry for, anxiously eager, yet always, at the very back of their hearts, a little haunting fear of what they might contain.

For several minutes they sat engrossed while occasionally one of them read a funny or characteristic extract over which they laughed happily.

For several minutes they sat engrossed while occasionally one of them read a funny or characteristic extract over which they laughed happily.

“Listen to this,” chuckled Mollie, while the girls looked up expectantly. “Frank says that Roy is getting terribly fat in spite of all the exercise—”

“Listen to this,” chuckled Mollie, while the girls looked up expectantly. “Frank says that Roy is getting terribly fat in spite of all the exercise—”

“Horrors!” interjected Grace.

“Horrors!” interjected Grace.

“And when he, Frank, ventured to remonstrate with him the other day and advised him to cut[10] down on his chow, Roy said: ‘Nothing doing! I’ve got a definite end in view, old man. This khaki outfit has acquired so much terra firma it’s beginning to stand alone, but if I get so fat I can’t wear it they’ll have to give me another one—see?'”

“And when he, Frank, ventured to remonstrate with him the other day and advised him to cut[10] down on his chow, Roy said: ‘Nothing doing! I’ve got a definite end in view, old man. This khaki outfit has acquired so much terra firma it’s beginning to stand alone, but if I get so fat I can’t wear it they’ll have to give me another one—see?'”

The girls laughed, but there was just a shade of wistfulness in their laughter, for they knew that the boys were only skirting the outer edge of the hardships they would be called upon to encounter later on.

The girls laughed, but there was just a shade of wistfulness in their laughter, for they knew that the boys were only skirting the outer edge of the hardships they would be called upon to encounter later on.

Then suddenly Betty gave a little cry of dismay.

Then suddenly Betty gave a little cry of dismay.

“Oh, girls,” she cried when they looked up at her fearfully, “it’s come! What we’ve been dreading so long! The boys have been ordered to the front!” [11]

“Oh, girls,” she cried when they looked up at her fearfully, “it’s come! What we’ve been dreading so long! The boys have been ordered to the front!” [11]

You got this now! Just click on words that don’t pop to mind!

CHAPTER II

BAD NEWS

The girls stared wide-eyed at Betty while slowly the color drained from their faces. It was true they had been dreading just this news for a long, long time, yet now that it had come they felt strangely quiet and numb. They had much the same feeling as one who had received a stunning blow. Until the paralysis had passed there could be no pain. That would come later.

“How do you know?” asked Mollie at last, in a voice that sounded strange even to herself. “Frank hasn’t mentioned it.”

“He will probably, toward the end,” Betty explained, while slowly her heart contracted and the tears welled to her eyes. “Allen didn’t—not till the last sentence. It’s only a line, but th-that’s enough. He says not to be alarmed if his letters are delayed—it may be hard to get them through.”

“They are going to the front,” Amy repeated dazedly, as if she found it hard to really believe. “When—did he say when, Betty?”[12]

“No, he didn’t,” said Betty slowly. “But you know Allen. He wouldn’t have said anything about it if the time hadn’t been pretty close at hand.”

“Why,” cried Grace, catching her breath as though the thought had just occurred to her, “they may be in the front line trenches now! They may be—they may be—”

And while the girls gazed at her in tragic silence, imagining terrible, unbelievable things, a moment will be taken to sketch briefly for the benefit of new readers the various exciting or amusing adventures which had befallen the Outdoor Girls in the days before the grim shadow of war had spread itself over the land.

In the first volume of the series, entitled “The Outdoor Girls of Deepdale,” the girls had formed a camping and tramping club and had tramped for miles over the country, meeting with many interesting adventures on the way.

After this, one good time had followed hard on the heels of another, first at Rainbow Lake, then at a winter camp where they had novel and interesting experience on skates and ice-boats.

At Ocean View some time later the Outdoor Girls had cleared up a mystery centering about a strange box they had found in the sand. Then had followed that splendid summer at Pine Island,[13] when the girls had accidentally discovered a gypsy cave and had succeeded not only in rounding up the band of gypsies but in recovering several valuable articles that had been stolen from them. The four boys who were now facing the enemy in France had shared in their fun that summer, pitching camp near the bungalow of the girls.

Their next adventure found the girls and boys again at Pine Island, but under greatly altered circumstances. America had just entered the great war, and the four boys had responded eagerly to the bugle call. Later they were sent to Camp Liberty for training, to which the girls soon followed them to work in the Hostess House.

Will Ford, the brother of Grace, had caused the girls, and especially his sister, anxiety and uneasiness because of his failure to enlist with the other boys. In the end he justified himself, however, by delivering a German spy to justice and enlisting in the service of his country immediately afterward. The girls also recovered some valuable jewelry that the spy had stolen from them.

Then in the volume directly preceding this, entitled “The Outdoor Girls at the Hostess House,” the girls had befriended an old woman who had[14] been knocked down by an unscrupulous motorcyclist. They later learned the secret tragedy in the life of their little old lady.

Now the girls had come home to Deepdale for a much needed rest, only to be confronted with the terrible, though, naturally, expected, news that the boys had been ordered to the front.

“Yes they may be, probably are, facing death at this minute,” said Mollie slowly, finishing the broken sentence. “Perhaps at the very minute we were playing and singing and enjoying ourselves—”

“Mollie, don’t!” cried Amy brokenly. “I don’t feel as if I could ever enjoy myself again.”

“Well, we’ve got to, whether we can or not,” said Betty, striving to control her quivering lips and tilting her little chin at a brave angle. “We can’t just lie down at the very first shot, you know.”

“You talk as if we were on the firing line,” said Grace hysterically.

“I suppose in a way we are,” returned the Little Captain slowly, wishing desperately that those troublesome tears would stay where they belonged—her eyes were so misty she could hardly see Grace! “Only ours is a harder kind of battle, because it’s made up mostly of waiting and working without any of the thrill and excite[15]ment of the real fight to help us. But I’d like to know,” and there was a little ring of pride and renewed courage in her voice, “what the real fighters would do without us anyway. We’re just as much soldiers as they are, and if we don’t do our share, they can’t do theirs.”

“Of course you are right, Betty dear, you always are!” cried Mollie, taking heart and even smiling a little. “We can’t do anybody good by moping.”

“No,” added Grace with a philosophy unusual in her. “That’s why we have the hardest share, I guess—because we have to keep gay and bright, no matter how we feel.”

“And we still have our work at the Hostess House,” Amy reminded them. “Maybe,” she added, a little wistfully, “if we work hard enough we’ll be able to forget—”

“What’s all this about working and forgetting?” cried Mrs. Nelson, coming gayly into the room. “I thought you had come home for a vacation.”

The girls explained, and Mrs. Nelson looked pityingly at their grave young faces.

“So that is it,” she was beginning, when Mollie sprang to her feet with a cry. She was staring at the paper that Mrs. Nelson had carelessly thrown on the table.[16]

“What is it?” they cried, as she snatched it up and read the glaring headlines.

“The Hostess House!” gasped Mollie. “Gone! Burnt up! Read this!”

Dazedly the girls obeyed, the big type seeming to strike them in the face as they read:

“Great Fire at Camp Liberty! Hostess House and Several Barracks Buildings Burned to the Ground!”[17]

CHAPTER III

MAKING PLANS

“I can’t seem to get used to it,” sighed Mollie several days later, as she ran up the steps of her porch and opened the screen door for the girls. “To think that no matter how much we want to go back to the Hostess House—”

“There is no Hostess House to go back to,” finished Grace, sinking down in a luxurious porch swing and plumping the cushion behind her back. Grace always had a gift for finding the soft places. “It is rather discouraging.”

“Just as we were going to work hard and forget how unhappy we were, too,” added Amy plaintively.

“Goodness, but we’re not going to be unhappy,” put in Betty, rocking vigorously. “I thought we decided that three days ago.”

“I know. But when we think—”

“But we musn’t think,” Betty interrupted quickly, adding with a little twinkle: “About being unhappy, that is. All we have to do is just hold on to the belief that the boys are coming[18] back a year from now, maybe less—coming back without a hair less than they had when they went away.”

“We didn’t count ’em,” said Mollie drolly. “The hairs, that is, so how can we tell?”

“Isn’t she funny?” drawled Grace, catching the pillow Mollie threw at her and depositing it calmly behind her back. “Thanks, old dear,” she said. “I just needed another one.”

“I thought we came to talk over the plans for our vacation,” Amy put in mildly, adding with a little laugh: “We have to take one now whether we want it or not.”

“But we haven’t the slightest idea what we’re going to do,” protested Grace. “I guess we’d just better stay at home and do nothing.”

“My, aren’t you encouraging?” cried Mollie, looking up indignantly from the pair of socks she was knitting. “You might at least suggest something.”

“Ooh, there you are!”

They turned suddenly to see a mischievous little face peeping at them from around the corner of the porch.

“Dodo, you little wretch, come here,” cried Mollie, trying to look severe and failing utterly.

“Now what mischief have you been up to?”

“No,” protested Dodo, shaking her curly head[19] vigorously, as she reluctantly abandoned her vantage point and came slowly toward Mollie. “No mischief ‘tall. Me an’ Paul jus’ playin’.”

This was Dora, nicknamed Dodo, and Paul, Mollie Billette’s small brother and sister, who were nearly always getting into some sort of mischief from the time they stepped their little feet out of bed in the morning till the time they slipped the same little feet, tired out with getting into trouble, into bed at night.

“You darling!” cried Betty, catching the little figure to her and administering a bear’s hug. “You’re terribly bad, but we can’t help loving you.”

“Uh-uh,” denied Dodo, wriggling free of Betty’s embrace and looking at her earnestly. “Me’s never bad—only Paul.”

“Ooh, Dodo Billette!” cried Paul, bursting in upon them from no one could quite tell where. “You’s a big story teller!”

“You’s the big ‘tory teller,” cried Dodo, coming sturdily to the rescue of her reputation. “You just go ‘way. Mol—lie, oh, Mollie, make him go ‘way!”

“Oh, dear!” cried Mollie, half amused and half vexed as she put aside her knitting and took Dodo on her lap. “I thought you and Paul promised to play with the bunnies all the after[20]noon and not bother sister. Can’t you see she has company?”

“Yes,” smiled the little girl, reaching up to pat Mollie’s cheek ingratiatingly. “Me an’ Paul got tired playin’ wiv bunnies an’ came to see you. We want,” she added succinctly, “tandies!”

“Well, you won’t get any, not this time,” said Mollie definitely, trying not to smile, while the other girls were not even trying. It was always hard not to laugh at the twins, naughty as they often were.

“Why?” demanded Dodo severely.

“Never mind why,” returned Mollie, putting the little girl down and taking up her knitting again. “Now run off, both of you, we want to talk.”

“But we want tandies,” repeated Dodo, looking surprised that Mollie had not understood the first time. “Dive Paul an’ me tandies—lots of tandies—an’ we’ll go ‘long. Shan’t we, Paul? Ooh—” the question ended in an anguished wail as Dora’s eyes rested on her faithless twin.

The latter had extracted Grace’s half-filled candy box from under a cushion where she had hastily hidden it at the first threat of invasion by the insatiable twins and was at the moment busily engaged in devouring its contents. Grace had been too busy watching Dodo to notice him.[21]

“Ooh, you bad boy! You bad boy!” wailed the little girl, making a dash for Paul, who deftly evaded her and took refuge behind Betty’s chair, “Div me dos tandies—dive ’em to me.”

“Can’t,” mumbled Paul, his mouth full, adding by way of explanation a convincing: “All gone.”

“Paul Billette, come here this minute,” commanded Mollie sternly, while Betty and Amy tried hard to check their rising mirth and Grace looked bereft. “Come here I say.”

“Make Dodo go ‘way then,” bargained Paul, adding in an explanatory tone: “Last time she pulled my hair.”

“An’ me’s goin’ do it ‘dain,” declared Dodo vengefully, when Betty reached over suddenly and pulled the little girl into her lap.

“Stay here a minute, Honey,” she coaxed, and as Dodo tried vainly to wriggle loose added: “Sister wants to speak to Paul.”

“An’ I,” said Dodo soberly, “want to pull his hair.”

Again the girls had to strangle their mirth while Mollie reiterated her command to Paul. The latter, after regarding the wriggling Dodo for a minute uncertainly, reluctantly left his refuge and stood before Mollie, head hanging.

“I’se sorry,” he said in a small voice, trying to[22] forestall the scolding he knew was coming. “Me never do it any more!”

“That,” said Mollie sternly, though the corners of her mouth twitched and there was a twinkle in her eye, “is just exactly what you say every time you’re a bad naughty boy. Now, just to make you remember how naughty you were, you shan’t have another piece of candy for a whole week.”

Paul’s protest was drowned in a wail from Dora.

“But me wants some tandies,” she cried. “Me didn’t take any.”

“She would, if Paul hadn’t seem them first,” murmured Grace, but Mollie shot her a warning glance.

“No,” she said, “and just for being such a good girl, sister’s going to give you six big chocolates all for yourself.”

Dodo gave a shout of glee and disengaging herself with one last frantic wriggle from Betty’s embrace, precipitated herself upon Mollie like a young cyclone.

“Ooh dive ’em to me, dive ’em to me quick,” she demanded, then as Mollie made good her promise the little girl turned upon the erring Paul a look of conscious virtue and said gravely; “If you were a dood boy I would div you one,[23] but now me’s goin’ eat ’em up, every one till dey’s all gone.”

Then she took to her heels, scurrying down the steps and around the corner of the house with Paul in hot pursuit.

“Dodo,” they heard him crying plaintively, “I’ll let you play wiv my best bunny if you will div me one candy, just one—”

“I wouldn’t give much for his chances,” chuckled Mollie, adding with a sigh that was a mixture of exasperation and amusement. “Aren’t they perfectly terrible? There isn’t a minute of the day when they’re not in some mischief.”

“No, they’re adorable,” cried Betty fondly. “I wouldn’t give two cents for children that didn’t get into mischief all the time.”

“I don’t care so much about the mischief,” said Grace, eyeing her empty chocolate box ruefully, “if they would only leave my candies alone.”

“Never mind, Gracie,” replied Mollie, laughing at her, “you shall have a whole box of mine, so you shall.”

“Fine,” agreed Grace, adding with a chuckle as Mollie handed over the almost full box: “Since my candies were more than half gone, I don’t call it such a bad bargain at that.”

“I’ll say it wasn’t,” dimpled Betty.

“Just the same,” said Mollie, after a little pause,[24] “even though the twins are a great deal of trouble, Mother said she just wouldn’t have known what to do without them—especially after I went to Camp Liberty—the house would have been so frightfully dull.”

“I should think so,” said Grace, adding suddenly, as though she had thought of it for the first time: “Why she would have been all alone, wouldn’t she? How awful!” For Mollie had no father, he having died several years before.

“And the other day she said the strangest thing,” Mollie continued, suddenly earnest. “You know how she adores Paul. Well, I caught her looking at him with the most wistful expression, and when I asked her what the matter was she looked up at me and I saw there were tears in her eyes.

“‘It’s Paul,’ she said softly. ‘Of course I’m thankful he is so little that I can keep him safe at home with me, but sometimes when I think of my dear country and the terrible wrongs she has suffered, I almost wish that my little son were old enough to bring retribution upon those hideous Germans. Sometimes I feel cheated—yes, you needn’t stare—that I have not a son “over there”.'”

“Oh, Mollie!” cried the Little Captain softly, “what a wonderful thing to say. And yet I think[25] she would die if anything happened to either of the twins.”

“That’s just it,” said Mollie, her eyes glowing with pride. “Loving them as she does, she almost wishes it were possible to make the supreme sacrifice for her country.”

“It was that spirit,” said Grace thoughtfully, “that won the battle of the Marne.”

For a long time after that the girls worked quietly, each busy with her own thoughts. It was Amy who finally broke the silence.

“And here we are,” she said plaintively, “letting another whole afternoon slip by without deciding what we are going to do on our vacation. Can’t somebody suggest something?”

“I have already suggested half a dozen things, only to be laughed to scorn,” said Mollie, adding decidedly: “I’m through.”

“And nothing I can say seems to meet with approval,” added Betty plaintively.

“Well,” said Grace, stretching herself, sitting up in the swing, and looking important, “nobody asks me whether I have anything to suggest,” adding as they turned a battery of surprised and eager glances her way: “I don’t know whether I can be persuaded to tell you now or not.”

“Tell us!” they cried, piling into the swing till the supporting ropes creaked with the strain.[26]

“Can’t we bribe you with candy?” pleaded Amy.

“No. I just made an advantageous trade in that article, you will remember,” was the answer.

“Anyway, we don’t bribe, we command,” put in Betty. “Grace, we refuse to be trifled with. What have you to suggest? Out with it!”

“You’d better hurry,” added Mollie, raising her knitting needle threateningly, “before I spit thee like a pig!”[27]

CHAPTER IV

GRACE SURPRISES HER CHUMS

“I’m not a pig,” cried Grace, striving to look dignified, which is a rather difficult procedure when one is being hugged by three pairs of arms at once. “I don’t care how many times you spit me, whatever that is, Mollie, but you shan’t call me a pig.”

“Of course she shan’t,” said Betty soothingly. “If she does it again, we’ll try our hand at this spitting business—”

“Goodness, sounds like a cat fight,” chuckled Grace, but Mollie unceremoniously shook her into attention.

“Grace, behave and tell us,” she ordered.

“What?” asked Grace aggravatingly, but added hastily as Mollie again raised the knitting needle at a threatening angle: “All right, if you’ll just give me space enough to breathe I’ll do any little thing you ask.”

With that the three jumped from the swing so suddenly that Grace, the only occupant left,[28] bounced into the air and landed with a thump on the cushions.

They laughed and drew up three chairs in a semi-circle in front of her to make escape impossible. Then three pairs of merry eyes focused commandingly upon her.

“I didn’t know it myself till last night,” she said in response to the tacit order. “Then it was patriotic Aunt Mary who proposed it.”

“Proposed what?” they cried.

“Well, that’s what I’m going to tell you if you give me half a chance. She said she felt as if she owed something to us girls for having stood so loyally behind Uncle Sam, and had decided to offer us her cottage at Bluff Point to use as long as we wanted it.”

“Bluff Point!” cried Betty, while her eyes began to sparkle. “Why Grace! isn’t that the place you were telling us about—”

“Where the quaint little house stands on a bluff—” added Amy eagerly.

“Overlooking a sparkling white beach that leads down to the ocean?” went on Betty.

“The very same,” nodded Grace, and they heaved a sigh of pure excitement and happiness.

“Isn’t it wonderful,” cried Mollie joyfully, “how somebody is always doing something to make us happy?”[29]

“Yes, but when I said that to Aunt Mary last night she smiled and looked wise—you know how sweet she is—and said that that was the way happiness always came to us—by helping others to be happy.”

“But we haven’t done anything to make anybody happy—particularly that is,” said Mollie wondering.

“I said that too,” nodded Grace. “But she only went on smiling, and I realized she must have meant our work at the Hostess House.”

“It’s strange how everybody persists in calling it work and giving us so much credit when it was all such fun,” said Betty. “But girls,” she added, laughing breathlessly, “the great fact is that we are going to have another adventure in the open. The very thought of it makes me want to roll in the buttercups.”

“Goodness, there’s one open in the back meadow,” suggested Mollie. “You can roll in it, if you want to.”

“Well, I don’t—I want a whole patch of them!” cried Betty, while the rest laughed at Mollie’s picture. “My, I feel younger already.”

“Well of course you need to,” drawled Grace, adding with a fond glance at the glowing Little Captain: “You look so terribly like a dried-up ancient, dear.”[30]

“But when shall we start?” cried Mollie, coming back to the all-absorbing topic at hand. “Goodness, I’d like to throw a few clothes in a suitcase and start right away—quick—this minute—I can’t wait!”

“Do you think it’s catching?” asked Grace, anxiously.

“From the way I feel I should say it was already caught,” twinkled Betty, adding eagerly: “How long do you suppose we will have to wait, Grace? Did your Aunt Mary say when we could have the cottage?”

“As soon as we want it,” replied Grace, looking surprised. “Didn’t I tell you?”

“No you didn’t,” mimicked Mollie, adding as she sprang to her feet impatiently: “I’d like to know what we’re waiting for anyway! Why don’t we get started?”

“Now I know she’s crazy,” cried Betty, seizing her chum and pulling her down upon the arm of her chair. “Why we haven’t decided anything yet.”

“What is there to decide?” cried Mollie, trying to be patient and looking like a martyr.

“Why we don’t even know how we’re going to get there yet,” explained Betty soothingly.

“In the automobile, of course,” cried Mollie, jumping up again.[31]

“Oh, can we?” cried Grace, forgetting to be languid and bouncing eagerly in the swing. “Mollie, that would be wonderful.”

“Why of course we’ll go in the car!” it was Mollie’s turn to look surprised. “What did you think we were going to do—walk?”

“There are railroads, you know,” Grace reminded her, relapsing into irony. “And as to walking—well, we did that too before you got your car, Mollie.”

“Yes, and got sore feet,” added Mollie.

“Well, now that we’ve decided not to go on the railroad or walk,” Amy broke in unexpectedly, “I really don’t see what we are waiting for.”

“My goodness, there’s another lunatic,” cried Grace, looking despairingly at the Little Captain, whose eyes twinkled merrily. “What do you expect us to do—go just as we are?”

“No, but we can throw some things into a suitcase—”

“How long do you suppose it will take us to get there?” asked the Little Captain, coming to Grace’s rescue.

“Why, even in Mollie’s car it will take two days,” said Grace, turning to Betty with the relief of one who at last had a sane person to reckon with. “Mollie and Amy evidently expect to make it in a couple of hours.”[32]

“Oh well, I didn’t know it was so far away,” murmured Mollie, somewhat taken aback. “Of course, then, we can’t go until to-morrow.”

The girls laughed merrily, and Betty hugged her.

“We might,” chuckled the latter, “even be forced to wait till day after to-morrow.”

“I won’t do it!” cried Mollie, jumping up again. “There’s no reason in the world why we can’t start to-morrow.”

“But, Mollie dear,” insisted Betty mildly, “we haven’t even asked our folks whether we may go or not—”

“As if we didn’t know what they will say,” broke in Mollie, but Betty went on without heeding her.

“And we must have a chaperone, you know.”

“Oh, I suppose so,” sighed Mollie sinking down in her chair resignedly, “but it’s horribly tiresome. I want to go now.”

“You sound like Dodo with her candies,” remarked Grace, amiably helping herself to a luscious milk chocolate filled with nuts. “Have one, Mollie—it may make you feel better.”

“It won’t, but I will,” said Mollie rather enigmatically, reaching out a hand for the proffered sweet. “Thank you, dear.”

“But whom shall we have for a chaperone?”[33] cried Amy impatiently. “I’m almost as bad as Mollie—I can hardly wait till to-morrow.”

“Why,” said Grace, nibbling daintily, “I thought maybe you girls wouldn’t mind if I asked mother to go with us.”

“Mind!” echoed Betty, while the others looked at her in surprise. “Why of course we’d love to have her! You know that. But I never imagined she would care to go, she is so interested in Red Cross work and her clubs—”

“That’s just it,” said Grace, sitting up quickly. “She’s entirely worn out with work and worry about Will, and I thought a little vacation with us girls would help her out wonderfully. I’m not sure she will go—I haven’t asked her yet.”

“Well, let’s,” cried Betty impulsively, jumping to her feet. “She simply can’t refuse if we all ask her at once.”

“Now you’re saying something!” cried Mollie fervently, albeit slangily, as she flung her arm about the Little Captain and dragged her down the steps. “Action is what we need—action, and plenty of it.”

The girls fairly ran the short distance from Mollie’s home to Grace’s, and the people they met on the way, greeted them heartily, musing as he or she turned to go on: “There’s probably something interesting in the air—the Outdoor Girls[34] always look like that when they have some new adventure in tow.” For Deepdale was very proud and fond of its Outdoor Girls.

Mrs. Ford was just coming down the stairs dressed to go out when the quartette burst in upon her. She did look very tired and worn, as Grace had said, but the smile that lighted her face at sight of the girls made her appear ten years younger.

“Mother,” said Grace, taking one of her mother’s carefully gloved hands in her own and leading her gently but firmly into the library, “we have something very important to say to you.”

“Will it take long?” queried Mrs. Ford, smiling at the other girls over her shoulder. “Because, if it will, I’m very much afraid I can’t wait. I’m a little late now.”

“That,” said Grace decidedly, as her mother sank into a chair and the other girls grouped themselves about her, “is exactly what we have come to talk about. We think you need a little vacation.”

“Vacation!” cried the lady, half rising from her chair. “Why, my dear! how can I take a vacation when my hands are so full of work now that I am—”

“You don’t have to take it,” Grace interrupted argumentatively, “we’ll just give it to you.”[35]

Mrs. Ford laughed helplessly and regarded the eager young faces with amusement.

“Out with it, girls,” she commanded. “I know you are plotting some terrible thing. What do you intend to do, kidnap me?”

“No, we’re keeping that for a last resort,” returned Betty, and Mrs. Ford laughed outright at the confession.

“We want,” explained Grace, speaking fast for fear of being interrupted, “to have you go with us to Bluff Point. We need a chaperone, you know.”

“I’ve no doubt of it,” retorted her mother, laughing, adding, with another anxious glance at the clock: “But I’m afraid you will have to get someone else, Honey. If I were free, I should like nothing better, but you see how rushed I am—”

“But you’re terribly tired, Mother, you know you are,” said Grace with unusual gentleness, adding diplomatically: “What good will you be to the Red Cross or to anyone else, I’d like to know, if you let yourself get sick?”

“But I’m not sick,” protested her mother, then added with a sudden longing as the wild solitude of Bluff Point rose before her eyes suggesting utter peace and quiet, a chance to rest tired nerves and gather strength for the last great drive:

“You’re right, I am tired, terribly tired,” and[36] the lines of weariness returning to her face. “I’d love it, girls, but there’s my work!”

It took the girls about five minutes of the hardest work they had ever done in their lives. But they did what they had set out to do. At the end of that time Mrs. Ford consented to start with them whenever they were ready.

“Day after to-morrow?” asked Mollie, her eyes shining.

“I don’t know why not,” said Mrs. Ford, then sprang to her feet with a cry of dismay. “Girls, I completely forgot to telephone the Red Cross. What will they think of me?”[37]

CHAPTER V

A PROBLEM SOLVED

“I wish,” said Mollie, sitting back to view approvingly the shining black hood of her car, “that we had another machine. I’m afraid by the time we’ve packed our bags and things into the tonneau we’ll find it rather crowded. And for such a long trip we ought to have plenty of room.”

“That’s what I was thinking,” agreed Amy, rubbing a bit of nickel to a gleaming polish, for the girls had gathered at Mollie’s to help her put the car in shape for the anticipated trip to Bluff Point. And they had gone to their work with a will, rubbing and polishing the big machine as they would have groomed a well-loved horse. “We will have our trunks sent, of course, but we shall have to take our nighties and combs and brushes and such things. We might put ’em on the roof,” she added hopefully.

“Yes, and we might wear ’em,” said Grace scornfully. “That is a brilliant idea.”

“Well, I have one worth two of that,” said Betty, trying not to look mysterious.[38]

“Betty, are you going to spring anything on us?” cried Mollie, while the other two paused with dust cloths uplifted.

“Not if you don’t want me to,” returned the Little Captain demurely.

“Betty, dear, I love you so,” crooned Mollie, running around the car and putting a rather oily hand about Betty’s waist. “You wouldn’t want such an ardent admirer to drop dead at your feet, would you, now?”

“It would have the charm of novelty,” chuckled Betty, only to add quickly as Mollie made a threatening gesture: “No, please don’t kill me yet. Come over here on the steps and I’ll tell you all about it.”

“Yes, yes, go on,” they cried, obediently ranging themselves on the steps of the back porch and fixing eager eyes upon her.

“Shoot!” Mollie commanded inelegantly.

“Well,” said Betty speaking slowly to add to the effect of her announcement, “I have a car!”

“A car!” they echoed, and Grace added: “Now I know she’s crazy!”

“When?” demanded Mollie, her eyes round and black, as they always were under excitement.

“If you mean, when did I get it,” answered Betty, enjoying their surprise to the full, “I might tell you that up to six o’clock last evening I had[39] no more idea of owning a car than you did. However, at six-fifteen, I owned it,” and her eyes danced with the pride of ownership.

Then the girls fell upon her, all demanding explanation of the miracle, till she raised her hand pleadingly.

“Give me a chance,” she begged. “How can I tell you anything when you’re making such a noise?”

The girls seemed impressed with the common sense of this. At any rate, they stopped talking for the space of a half a minute.

“It was last night at dinner,” explained Betty hurriedly, seizing her opportunity. “Dad came in a little late, and as he sat down he laughingly asked us how we would like a racing car in the family.”

“A racing car!” they echoed.

“Of course we thought he was joking,” continued Betty, “but when we found he was very much in earnest of course we went wild with excitement.”

“I should think so,” breathed Amy.

“But, Betty darling, how—” Mollie was beginning when Betty cut her short by hurrying on with her story.

“That’s what we wanted to know, of course,” she said. “It seems that one of Dad’s clients owed[40] him a good deal of money, and although he, the client, that is, had plenty of money, it was all tied up in such a way that he couldn’t get hold of it right away, so he offered to give Dad his almost new racing car in exchange. And,” here Betty came to the most wonderful part of her story, “since mother doesn’t care for that type of car—he gave it to me!”

“Betty, how mar-ve-lous!” breathed Mollie, while Amy and Grace just stared.

“Can we see it? Have you got it at home?” asked Amy, after a few minutes during which the girls had been getting used to the wonderful idea of Betty with a machine, and a racing machine at that.

“Oh, Betty, lead us to it,” added Mollie yearningly.

“I don’t know whether it’s come yet or not,” explained the Little Captain, as the girls threw aside dust rags and gingham aprons preparatory to a concerted rush upon the new acquisition. “That’s why I didn’t tell you about it sooner. I was going to surprise you by taking you to it,” she added, as they set off at a walk that was almost a run for the pretty Nelson house; “but when Mollie spoke about another car I just couldn’t hold back any longer. Oh dear, I hope it has come!”[41]

“Won’t it be fun?” cried Mollie joyfully, executing a little irrepressible skip in her delight. “You can run it, Betty, of course, and take Grace or Amy with you while our car comes behind—”

“With the luggage,” finished Betty wickedly.

“Well you needn’t be so conceited,” retorted Mollie, her nose in the air, while Betty looked innocent.

“Wasn’t that what you were going to say?” she inquired.

However, there was no time for more conversation, for at that moment they turned a corner, bringing Betty’s house to sight, and what should be going up the drive at that particular and ecstatic moment but the graceful, low-bodied racer itself!

With a shout the girls rushed forward. They overtook the driver as he slowed to a stop, and fairly danced with impatience while the man pushed up his goggles, took off his hat, wiped his perspiring forehead, and slowly turned to smile at them.

“This is where Mr. Nelson lives, isn’t it?” he asked. “Mr. Todd asked me to bring the car around—”

“Yes, yes, we know all about it,” interrupted Betty, then added with a smile, as the man looked surprised: “I suppose you think I’m terribly im[42]patient, but, you see, the car is mine, and I can’t wait to try it out.”

The man whistled and descended with alacrity. The girls noticed rather absentmindedly that he was a rather good looking young fellow, probably one of the young men from Mr. Todd’s office who had volunteered to run this errand for him.

“Well, I don’t blame you a bit for being in a hurry,” he said heartily, eyeing the beautiful lines of the car with approval. “She sure is a great little machine! You are Miss Nelson, I suppose?” he added, turning to Betty. “You see,” with evident embarrassment, “I promised to deliver the car in person to Mr. Nelson—”

“Here he is, so there ought to be no difficulty about that,” said a jovial voice, and they turned to find Mr. Nelson himself coming toward them. “Good afternoon, Mr. Jameson. How do you like my new acquisition? A beauty is it not?”

“I say so!” agreed the young fellow, and after a few moments of general conversation, Mr. Nelson led him off toward the house, leaving the girls to themselves. And that, as Mollie afterward remarked, “was just the most beautiful thing he could have done!”

Before they had turned the corner of the house, Betty had clambered in behind the steering wheel and was bidding the girls follow.[43]

In their excitement they all tried to climb in, forgetting that a car designed to seat two people cannot by any stretch of imagination accommodate four. Then suddenly realizing what an absurd picture they must be making, they began to laugh.

“Well, now what are we going to do?” wailed Mollie. “We can’t all go at once.”

“Of course you can,” cried Betty busily examining her treasure, touching a lever here, a button there, with loving fingers. “What, may I ask, is the matter with the running boards?”

“Betty, you don’t mean—”

“Yes, I do,” firmly.

“But we can’t—”

“Well, then I’ll have to take one at a time,” decided Betty, tooting the horn experimentally. “Come on—who goes first?”

“Oh, come on, we’ll all go,” cried Mollie dancing with impatience. “You get in beside Betty, Grace, since you’re afraid of the running board, and Amy and I’ll hang on somewhere. Come on, Amy. Be a sport, old girl.”

Amy wavered for a moment, but the challenge was too much for her, and she nodded her head in assent.

“Thank goodness I can only die once,” was her cheerful comment.[44]

So Grace climbed in beside the Little Captain, while Amy and Mollie scrambled up on the running boards and clung to the sides of the car. Then Betty tooted the horn triumphantly and began slowly to back down the drive.

“I don’t know about this,” she remarked, as the car made rather zigzagging work of it. “I’ve driven mostly on a straight road, you know, and I’m not very expert, even if I do know all about a motor boat.”

“So we see,” commented Mollie wickedly, as Betty nearly backed into a flower bed at one side of the drive.

“Don’t you think we’d better get off?” asked Amy. “Till you turn into the road, anyway, Betty?” she added.

“Don’t you dare,” cried Betty, giving the wheel a nervous little twist that caused Amy to groan and clutch the side of the car tighter. “If you make me stop now, I’ll never get started again. There!” as the car slid into the roadway, hesitated a moment, then without a jar or a jerk, glided swiftly along the smooth road, gathering headway as it went. “Now we’re all right.”

“That was pretty work, Betty,” complimented Mollie, who, as an old and experienced driver, felt capable of pronouncing judgment. “Now let’s see what this little car will do.”[45]

“Not too fast,” begged Amy, as Betty slid into high gear. “Remember we’re not used to this kind of traveling, and we’re apt to find ourselves sitting in the road if you’re not careful.”

“Have you chosen your spot?” asked Betty, her eyes twinkling.

“Just the same, it might have been a good idea to have brought some cushions along,” said Mollie ruefully. “We might have strapped them on and used them the way you do life savers—in case of emergency.”

“My, you must be having a wonderful time,” drawled Grace. “Have some candy Mollie—it may help your courage.”

“My courage doesn’t need any help, thank you,” snapped Mollie, adding wickedly: “Just for that we ought to make you ride out here.”

“Goodness, don’t!” cried Betty, as she swung the car around a corner and started once more toward home. “The punishment wouldn’t fit the crime, Mollie. Besides, we’ll be back in a few minutes. Girls, she runs like a dream!”

“She’s a wonder,” agreed Mollie. “I guess there’s just about no limit to the speed she’s capable of.”

“Do you want me to let her out?” queried Betty wickedly, but both Amy and Mollie protested vehemently.[46]

“Some other time,” said Mollie, “when we’re not hanging on by our eyelids!”

A few minutes more, and they were again turning into the Nelson drive, which, by the way, Betty took much more expertly this time. As the car slowed, Amy and Mollie dropped off and Amy opened the door for Lady Grace, who descended slowly.

“Well, how do you like it?” cried Betty, jumping out in her turn and regarding her new possession with shining eyes. “Do you think she’ll do?”

“Do!” they cried, and Mollie added, patting the smooth side of the car with admiring fingers:

“She’s a wonder, Betty—as Roy would say, ‘a perfect pippin.’ Good-bye,” she added suddenly, starting down the drive.

“Where are you going?” cried Betty, as they looked after her surprised.

“Home,” she answered, adding with a chuckle: “I’ve got to finish cleaning my old car. It’s poor old nose must be terribly out of joint.”[47]

CHAPTER VI

LIFE AND DEATH

The next morning Betty awoke to the sound of the telephone ringing imperatively in the hall. She got up, dragged the instrument from its stand and spoke drowsily into the receiver.

“Hello—who—why, Grace, how did you happen to wake up?—Why, Grace, what is the matter, dear?—You have heard what?—Will is wounded?—Oh, Honey, how awful! Is it serious?—Never mind, don’t try to tell me about it now. I’ll get dressed just as fast as I can and come right over—Yes, yes, in about five minutes.”

Mechanically Betty replaced the receiver on the hook and hurried back into her room. Then swiftly she began to dress.

Will! Dear old Will was wounded! That had been about all she had been able to gather from Grace’s sobbing message—but that was enough. He was the first of the boys to fall out there in the trenches, and who knew but what Allen might be the next!

And here only yesterday they had been so[48] happy, as happy as they could be with that shadow always hanging over them. This was the day, too—the incongruous thought struck Betty as she hastily pulled on her clothing—the day they had set for their trip to Bluff Point. Well, of course, it was all off now. Who wanted to go anyway?

These thoughts and many more raced through Betty’s head as she put the finishing touches to her toilet and crushed a garden hat on her pretty soft hair. She was a very attractive picture as she ran down the stairs, but she neither knew it nor cared.

“Why, Betty dear, what is the meaning of the hat?” her mother inquired, smiling as her young daughter burst into the dining room. “You don’t need it to eat breakfast in, you know. Who called on the ‘phone?”

“I’m not going to eat breakfast, at least not right away. But there, of course, you don’t know,” answering her mother’s look of surprise. “Grace called up and, oh, Mother, poor Will has been wounded! I don’t want to c-cry,” her chin quivered and she turned away for a moment to get control of the lump in her throat.

“I know, dear,” said her mother, putting an understanding arm about her, “and so I’m not going to offer very much sympathy—just now. Were you going over to see Grace, poor child?”[49]

Betty squeezed her mother’s hand gratefully and nodded.

“I’ll be back in a little while,” she said finally, getting the better of that annoying lump. “I just want to find out all about it and give Grace my sympathy.”

And the Little Captain found poor Grace in need of all the sympathy she could possibly give her. She was sitting in the darkest corner of the library, all crumpled up in a big chair, her eyes red with weeping and a damp ball of handkerchief clutched tightly in one hand.

At sight of Betty running toward her, she began to sob again, the tears running down her face unnoticed.

“Betty, Betty, I knew you’d come,” she cried, as Betty knelt beside her and put two loving arms about her. “I’m so m-miserable I just don’t want to live at all.”

“But, Honey, it isn’t nearly as bad as it might be,” said Betty, trying to sooth while wanting desperately to know herself just how bad it was. “You said he was only wounded, didn’t you?”

“That’s what the telegram said,” Grace answered, wiping her eyes drearily. “But how do we know but what he may be dead by this time?”

“We don’t know, of course,” returned Betty, recovering a little of her optimism while she unos[50]tentatiously handed Grace a fresh handkerchief, “but the chances are against it.”

“But perhaps they said he was just wounded to l-let us down easy,” cried Grace, evidently convinced that there was no bright side to look upon.

“The Government doesn’t do that; it hasn’t time,” argued Betty. “It always lets you know the worst at once.”

A gleam of hope came into Grace’s eyes.

“Then you think there’s a chance?” she queried, sitting up straight and beginning to look a little more interested in life. “Do you think he may get well?”

“Why, of course,” said Betty, adding reasonably: “If you would tell me just what the telegram said, I’d have more to go on.”

“That’s all it said—what I told you,” replied Grace, relaxing wearily. “Just said that he was wounded—nothing more. Dad is writing to Washington to try to get more news. Of course, he has a great deal of influence, being a lawyer with a good many friends in Washington, and he may be able to find out something. I don’t know.”

“Here come Mollie and Amy,” said Betty, glancing through the window. “I guess,” she added thoughtfully, “Amy probably feels pretty bad too.”

“But she’s not his sister,” cried Grace, with a[51] sudden flare-up of jealousy that made Betty smile in spite of her heartache. She could not help wondering how Grace would have taken it if it had been Roy instead of Will who had been wounded.

But Grace’s little fit of jealousy did not last long at sight of Amy’s drawn, white face and the traces of tears in her eyes. Instead, she opened her arms to this other girl who was not Will’s sister, yet loved him too, and for a moment they cried on each others shoulders.

Meanwhile Betty and Mollie wandered over to the window and stood looking thoughtfully out upon the lawn and not seeing any of it.

“Goodness!” said Mollie after a moment, shrugging her shoulders a little impatiently, “of course, it’s terrible to have Will wounded, and I can imagine Grace being all cut up about it, but she—and Amy too—act as if he were dead.”

“I know,” said Betty softly, then added, looking a little quizzically at Mollie; “But you know I don’t blame them so much when I try putting myself in their place. Of course we love Will, but suppose it had been Allen, for instance, or Frank.”

Mollie started and uttered a little cry of protest.

“Oh, but that would be different,” she said weakly, then catching Betty’s eye, added soberly: “I see what you mean, of course. I suppose I[52] would act just the same, under different circumstances.”

However, having had their cry out and feeling better and much more cheerful in consequence, Grace and Amy called to them and they crossed the room quickly.

“We’ve decided,” said Amy then, “that, since we can’t find out any more until Mr. Ford hears from Washington, we might as well make the best of it.”

“And we want to talk about our trip,” Grace added.

“Our trip?” echoed Mollie. “Why I thought of course we would give that up.”

“I did too,” explained Grace. “But when I spoke of it to Dad, he said we were to do nothing of the kind. He said we couldn’t do poor Will”—in spite of all her resolution her voice broke on the name—”any good by staying at home and moping, and that he would let us know as soon as he had any authentic word from Washington. And he insists on mother’s going too.”

And so it happened that a few hours later a very sober group of Outdoor Girls started on what should have been a joyful trip, with heavy hearts and gloomy foreboding. Even the new racer did not serve to liven the party.

The only time they laughed was when they[53] found Dodo and Paul, the incorrigible twins, hidden away under some raincoats in Mollie’s car.

“Oh, but we want to go ‘long,” Dodo protested vehemently when discovered.

“We just got to go ‘long,” Paul had added.

“No, you mustn’t ‘got to,'” Mollie contradicted them, while the others looked on amused. “Come, Dodo, honey, be a good girl for sister and come down. You too, Paul. We’re in an awful hurry.”

“But we not goin’ to come down,” Dodo insisted.

“‘Less,” Paul added diplomatically, “we get tandies.”

“Lots of tandies,” Dodo supplemented.

“Here, take these,” Grace offered, holding out a box of sweets which, despite all her trouble, she had not forgotten.

“Don’t give them the box—just take out a few,” Mollie suggested, but Grace insisted, while her face clouded again.

“I don’t want them, anyway. I don’t know why I took them. Habit, I suppose.”

However, hope and optimism did not consent to be kept long in the background on such a day as this when the sun shone its brightest and the birds sang their hardest and the very wind seemed to be whispering of happier times to come.

“Well,” sighed Amy at last, for she and Mrs.[54] Ford were riding in Mollie’s car, while Grace was with Betty in the racer, “it’s plain to be seen that nature at least doesn’t know that anything horrible or cruel is happening ‘over there.’ I don’t think I ever saw a more wonderful day.”

“Maybe it is a good omen,” said Mollie, quick to seize her opportunity. “I feel it in my bones that it won’t be long before we will hear good news of Will—and you know my prophetic bones never lie.”

“I don’t know anything of the sort,” protested Amy, although the remark brought a reluctant smile to her lips. “I’ve known those same prophetic bones to slip up before this.”

“Which reminds me,” Mollie cried, apropos of nothing in particular, “that if we don’t put on more speed we’ll not reach our destination before dark. I wonder why Betty doesn’t hurry,” for Betty and Grace in the speedy little racer were taking the lead.

She signaled the latter with three long and three short toots of the horn. A moment later the racer slowed down and Betty turned around to see what was wanted.

“You’re too slow,” cried Mollie. “If you don’t go a little faster, we’ll have to run over you.”

“Oh-ho, look who’s talking!” gibed the Little Captain, adding wickedly: “We were afraid to[55] speed up for fear of leaving you too far behind.”

“Now I know we’ll have to run over you,” cried Mollie fiercely. “Toot, toot—out of my way!”

But Betty evidently had no intention of getting out of anybody’s way, for with a challenging blast of her horn she put the little car at high and it sprang forward gleefully.

Behind her, Mollie’s car, like a big cat after a mouse, gave exultant chase, fairly eating up the road. And yet Betty maintained the distance between them—even drew away a little.

“Goodness,” cried Mollie suddenly, her eyes sparkling, “I may be mistaken, but I think she wants a race!”[56]

CHAPTER VII

THE RACE

Then began some fun that was novel and exciting even to the Outdoor Girls, who thought they had tried just about every sport there was.

Mollie bent her straight little back over the steering wheel, gave her more power and the big car fairly flew ahead, lessening perceptibly the distance between it and the racer.

However, Betty, looking behind, seemed not in the least concerned. On the contrary, she waved her hand joyously as she recognized Mollie had taken her challenge. Then she too bent over the wheel with her eyes glued to the flying ribbon of road ahead.

“Betty, Betty, stop it!” cried Grace, holding frantically to her hat and the side of the car. “Suppose we should m-meet somebody—a wagon or a m-machine.”

“So much the worse for it,” retorted Betty gayly. “You keep your eye on Mollie, Gracie dear, and tell me whether she’s gaining—that’s a good girl.”[57]

“If you think I’m going to help you break our necks—” Grace sputtered, but Betty cut her short.

“Well, if you don’t I will have to look for myself,” she said, adding maliciously: “And then we will have a smash-up!”

Grace groaned and looked behind her.

“They’re gaining,” she cried, and then all at once the spirit of the thing caught her—the contest of speed was getting into her blood. “Oh, Betty, don’t let ’em,” she almost screamed, above the noise of the motor and the rushing wind. “They’re not more than fifty feet behind now!”

Betty gave her a swift look, smiled to herself, and once more fixed her dancing eyes on the road ahead.

“All right,” she crowed. “Just watch me run away from them. I wouldn’t have had the heart,” she added with a chuckle, “if Mollie hadn’t brought it all on herself.”

“But they’re still gaining,” insisted Grace nervously, trying to look behind, ahead, keep her seat, hat, and dignity all at the same time. “Look, Betty, they’re only about thirty feet behind!”

“That’s near enough,” Betty decided, and leaning over suddenly, did something to the car that Grace never quite understood. Anyway, it had the desired effect. The little racer fairly leapt forward and, like a horse that has been given his[58] head for the first time, took the bit between its teeth and bolted.

Behind them Mollie looked her amazement. She was getting every bit of speed out of her machine of which it was capable, and then, just as victory was within sight, Betty was doing an inconceivable, unbelievable thing—she was winning the race!

Mrs. Ford and Amy had been enjoying the race tremendously, but now they leaned forward in surprise.

“Goodness, she’s beating us,” cried Amy.

“No!” snapped Mollie sarcastically. “Who would have supposed it?”

“Perhaps it is because Betty’s car is so much lighter,” suggested Mrs. Ford consolingly. “We have all the luggage and wraps, too.”

“Oh, that wouldn’t make so much difference,” denied Mollie, who was too good a sportsman to make excuses for herself. “Betty’s racer has the speed, that’s all.”

“Well, they’re just about out of sight now,” said Amy, leaning back resignedly. “I only hope Betty doesn’t run into anything and have a smash-up. She hasn’t driven a car as much as you, Mollie.”

“Oh, Betty’ll take care of herself,” said Mollie, though she was slightly mollified by this tribute to[59] her superior experience, if not superior speed. “I guess,” she added, after a moment’s reflection, “I’d better sell this old car and get a racer too.”

Mrs. Ford laughed softly, the first time she had laughed or thought of laughing since receiving the news of Will’s being wounded.

“Don’t go back on an old friend for its first offence, Mollie,” she chided, adding diplomatically: “A racing car is just fine for speed, but I think your automobile is much more sociable and comfy.”

“Well, I’m glad there’s something nice about it,” said Mollie, for she had not yet recovered from her surprise and chagrin. “I hope,” she added, as a sudden thought struck her, “that Betty doesn’t get too far ahead. I don’t know this part of the country very well and Betty has the map.”

“That will be the next thing,” said Amy, with a sigh, and Mollie looked at her sharply.

“What?” she demanded.

“Why, that we’ll get lost,” Amy explained. “Wasn’t that what you meant?”

“Oh, I hope not,” said Mrs. Ford, a little anxiously. “Perhaps we’ll be able to see them when we round this curve, Mollie.”

But they rounded several curves, and still no sign of Betty’s car. Then happened what Mollie had secretly been fearing would happen. They[60] came to a crossroads and a sudden stop at one and the same moment.

“Now, what?” queried Amy, in the tone of resignation that never failed to rub Mollie the wrong way. “Something the matter with the engine?”

“No, the engine’s all right,” snapped Mollie, adding, irritably: “But everything else is all wrong.”

“What, for instance?” queried Mrs. Ford soothingly. She knew that the first defeat Mollie had ever experienced would be bound to rankle and was prepared to make allowances. “If the engine is all right, why don’t we go on?”

“Which way?” queried Mollie, spreading out her arms with a hopeless gesture. “There are two roads, one looks as good as the other, and we haven’t the slightest idea in the world which to take.”

“Oh!” gasped Amy.

Mrs. Ford gave a low whistle as she saw the fix they were in.

“Then if Betty doesn’t realize our predicament and come back pretty soon, we’ll either have to stay here indefinitely, or go back the way we came, is that it?”

“Yes,” nodded Mollie, adding truthfully and more than a little anxiously: “Only I’m not quite[61] sure I know just how we came. As I said, this is unfamiliar country to me.”

Amy groaned.

“Then we shall be lost for fair,” she said. “Oh, why did Betty do such a foolish thing?”

Mollie was about to retort when a cloud of dust in the distance and a faint chug-chug made her swallow her words.

“What’s that?” she cried. “It sounds like a motor. I wonder—”

“Yes, it is!” cried Amy, straining her eyes to see through the cloud of dust. “It’s only a little car, and it’s coming at about ninety miles an hour.”

At this reference to Betty’s speed, Mollie winced a little but gave a relieved sigh nevertheless. For by this time the car was near enough to be identified beyond doubt. It was a racer, and there was a girl at the wheel.

A few moments later Betty herself, with a grin, hailed them.

“Hello,” she cried, adding as the car slowed to a standstill: “This time the joke’s on us. We were so busy running away from you that we took the wrong road. This one ends about two miles up in somebody’s farm.”