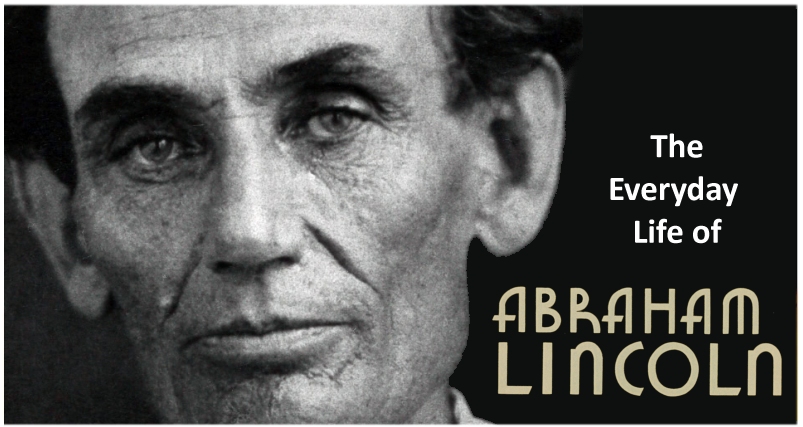

THE EVERY-DAY LIFE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN

A NARRATIVE AND DESCRIPTIVE

BIOGRAPHY WITH PERSONAL RECOLLECTIONS

BY THOSE WHO KNEW HIM

BY FRANCIS FISHER BROWNE

Index About this Book Footnotes

CONTENTS

Ancestry—The Lincolns in Kentucky—Death of Lincoln’s Grandfather—Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks—Mordecai Lincoln—Birth of Abraham Lincoln—Removal to Indiana—Early Years—Dennis Hanks—Lincoln’s Boyhood—Death of Nancy Hanks—Early School Days—Lincoln’s First Dollar—Presentiments of Future Greatness—Down the Mississippi—Removal to Illinois—Lincoln’s Father—Lincoln the Storekeeper—First Official Act—Lincoln’s Short Sketch of His Own Life

A Turn in Affairs—The Black Hawk War—A Remarkable Military Manoeuvre—Lincoln Protects an Indian—Lincoln and Stuart—Lincoln’s Military Record—Nominated for the Legislature—Lincoln a Merchant—Postmaster at New Salem—Lincoln Studies Law—Elected to the Legislature—Personal Characteristics—Lincoln’s Love for Anne Rutledge—Close of Lincoln’s Youth

Lincoln’s Beginning as a Lawyer—His Early Taste for Politics—Lincoln and the Lightning-Rod Man—Not an Aristocrat—Reply to Dr. Early—A Manly Letter—Again in the Illinois Legislature—The “Long Nine”—Lincoln on His Way to the Capital—His Ambition in 1836—First Meeting with Douglas—Removal of the Illinois Capital—One of Lincoln’s Early Speeches—Pro-Slavery Sentiment in Illinois—Lincoln’s Opposition to Slavery—Contest with General Ewing—Lincoln Lays out a Town—The Title “Honest Abe”

Lincoln’s Removal to Springfield—A Lawyer without Clients or Money—Early Discouragements—Proposes to become a Carpenter—”Stuart & Lincoln, Attorneys at Law”—”Riding the Circuit”—Incidents of a Trip Round the Circuit—Pen Pictures of Lincoln—Humane Traits—Kindness to Animals—Defending Fugitive Slaves—Incidents in Lincoln’s Life as a Lawyer—His Fondness for Jokes and Stories

xvi

Lincoln in the Legislature—Eight Consecutive Years of Service—His Influence in the House—Leader of the Whig Party in Illinois—Takes a Hand in National Politics—Presidential Election in 1840—A “Log Cabin” Reminiscence—Some Memorable Political Encounters—A Tilt with Douglas—Lincoln Facing a Mob—His Physical Courage—Lincoln as Duellist—The Affair with General Shields—An Eye-Witness’ Account of the Duel—Courtship and Marriage

Lincoln in National Politics—His Congressional Aspirations—Law-Partnership of Lincoln and Herndon—The Presidential Campaign of 1844—Visit to Henry Clay—Lincoln Elected to Congress—Congressional Reputation—Acquaintance with Distinguished Men—First Speech in Congress—”Getting the Hang” of the House—Lincoln’s Course on the Mexican War—Notable Speech in Congress—Ridicule of General Cass—Bill for the Abolition of Slavery—Delegate to the Whig National Convention of 1848—Stumping the Country for Taylor—Advice to Young Politicians—”Old Abe”—A Political Disappointment—Lincoln’s Appearance as an Officer Seeker in Washington—”A Divinity that Shapes Our Ends”

Lincoln again in Springfield—Back to the Circuit—His Personal Manners and Appearance—Glimpses of Home-Life—His Family—His Absent-Mindedness—A Painful Subject—Lincoln a Man of Sorrows—Familiar Appearance on the Streets of Springfield—Scenes in the Law-Office—Forebodings of a “Great of Miserable End”—An Evening Whit Lincoln in Chicago—Lincoln’s Tenderness to His Relatives—Death of His Father—A Sensible Adviser—Care of His Step-Mother—Tribute From Her

Lincoln as a Lawyer—His Appearance in Court—Reminiscences of a Law-Student in Lincoln’s Office—An “Office Copy” of Byron—Novel Way of Keeping Partnership Accounts—Charges for Legal Services—Trial of Bill Armstrong—Lincoln before a Jury—Kindness toward Unfortunate Clients—Refusing to Defend Guilty Men—Courtroom Anecdotes—Anecdotes of Lincoln at the Bar—Some Striking Opinions of Lincoln as a Lawyer

xvii

Lincoln and Slavery—The Issue Becoming More Sharply Defined—Resistance to the Spread of Slavery—Views Expressed by Lincoln in 1850—His Mind Made Up—Lincoln as a Party Leader—The Kansas Struggle—Crossing Swords with Douglas—A Notable Speech by Lincoln—Advice to Kansas Belligerents—Honor in Politics—Anecdote of Lincoln and Yates—Contest for the U.S. Senate in 1855—Lincoln’s Defeat—Sketched by Members of the Legislature

Birth of the Republican Party—Lincoln One of Its Fathers—Takes His Stand with the Abolitionists—The Bloomington Convention—Lincoln’s Great Anti-Slavery Speech—A Ratification Meeting of Three—The First National Republican Convention—Lincoln’s Name Presented for the Vice-Presidency—Nomination of Fremont and Dayton—Lincoln in the Campaign of 1856—His Appearance and Influence on the Stump—Regarded as a Dangerous Man—His Views on the Politics of the Future—First Visit to Cincinnati—Meeting with Edwin M. Stanton—Stanton’s First Impressions of Lincoln—Regards Him as a “Giraffe”—A Visit to Cincinnati

The Great Lincoln-Douglas Debate—Rivals for the U.S. Senate—Lincoln’s “House-Divided-against-Itself” Speech—An Inspired Oration—Alarming His Friends—Challenges Douglas to a Joint Discussion—The Champions Contrasted—Their Opinions of Each Other—Lincoln and Douglas on the Stump—Slavery the Leading Issue—Scenes and Anecdotes of the Great Debate—Pen-Picture of Lincoln on the Stump—Humors of the Campaign—Some Sharp Rejoinders—Words of Soberness—Close of the Conflict

A Year of Waiting and Trial—Again Defeated for the Senate—Depression and Neglect—Lincoln Enlarging His Boundaries—On the Stump in Ohio—A Speech to Kentuckians—Second Visit to Cincinnati—A Short Trip to Kansas—Lincoln in New York City—The Famous Cooper Institute Speech—A Strong and Favorable Impression—Visits New England—Secret of Lincoln’s Success as an Orator—Back to Springfield—Disposing of a Campaign Slander—Lincoln’s Account of His Visit to a Five Points Sunday School

xviii

Looking towards the Presidency—The Illinois Republican Convention of 1860—A “Send-Off” for Lincoln—The National Republican Convention at Chicago—Contract of the Leading Candidates—Lincoln Nominated—Scenes at the Convention—Sketches by Eye-Witnesses—Lincoln Hearing the News—The Scene at Springfield—A Visit to Lincoln at His Home—Recollections of a Distinguished Sculptor—Receiving the Committee of the Convention—Nomination of Douglas—Campaign of 1860—Various Campaign Reminiscences—Lincoln and the Tall Southerner—The Vote of the Springfield Clergy—A Graceful Letter to the Poet Bryant—”Looking up Hard Spots”

Lincoln Chosen President—The Election of 1860—The Waiting-Time at Springfield—A Deluge of Visitors—Various Impressions of the President-Elect—Some Queer Callers—Looking over the Situation with Friends—Talks about the Cabinet—Thurlow Weed’s Visit to Springfield—The Serious Aspect of National Affairs—The South in Rebellion—Treason at the National Capital—Lincoln’s Farewell Visit to His Mother—The Old Sign, “Lincoln & Herndon”—The Last Day at Springfield—Farewell Speech to Friends and Neighbors—Off for the Capital—The Journey to Washington—Receptions and Speeches along the Route—At Cincinnati: A Hitherto Unpublished Speech by Lincoln—At Cleveland: Personal Descriptions of Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln—At New York City: Impressions of the New President—Perils of the Journey—The Baltimore Plot—Change of Route—Arrival at the Capital

Lincoln at the Helm—First Days in Washington—Meeting Public—Men and Discussing Public Affairs—The Inauguration—The Inaugural Address—A New Era Begun—Lincoln in the White House—The First Cabinet—The President and the Office-Seekers—Southern Prejudice against Lincoln—Ominous Portents, but Lincoln not Dismayed—The President’s Reception Room—Varied Impressions of the New President—Guarding the White House

Civil War—Uprising of the Nation—The President’s First Call for Troops—Response of the Loyal North—The Riots in Baltimore—Loyalty of Stephen A. Douglas—Douglas’s Death—Blockade of Southern Ports—Additional War Measures—Lincoln Defines the Policy of the Government—His Conciliatory Course—His Desire to Save Kentucky—The President’s First Message to Congress—Gathering of Troops in Washington—Reviews and Parades—Disaster at Bull Run—The President Visits the Army—Good Advice to an Angry Officer—A Peculiar Cabinet Meeting—Dark Days for Lincoln—A “Black Mood” in the White House—Lincoln’s Unfaltering Courage—Relief in Story-Telling—A Pretty Good Land Title—”Measuring up” with Charles Sumner—General Scott “Unable as a Politician”—A Good Drawing-Plaster—The New York Millionaires who Wanted a Gunboat—A Good Bridge-Builder—A Sick Lot of Office-Seekers

Lincoln’s Wise Statesmanship—The Mason and Slidell Affair—Complications with England—Lincoln’s “Little Story” on the Trent Affair—Building of the “Monitor”—Lincoln’s Part in the Enterprise—The President’s First Annual Message—Discussion of the Labor Question—A President’s Reception in War Time—A Great Affliction—Death in the White House—Chapters from the Secret Service—A Morning Call on the President—Goldwin Smith’s Impressions of Lincoln—Other Notable Tributes

Lincoln and His Cabinet—An Odd Assortment of Officials—Misconceptions of Rights and Duties—Frictions and Misunderstandings—The Early Cabinet Meetings—Informal Conversational Affairs—Queer Attitude toward the War—Regarded as a Political Affair—Proximity to Washington a Hindrance to Military Success—Disturbances in the Cabinet—A Senate Committee Demands Seward’s Removal from the Cabinet—Lincoln’s Mastery of the Situation—Harmony Restored—Stanton becomes War Secretary—Sketch of a Remarkable Man—Next to Lincoln, the Master-Mind of the Cabinet—Lincoln the Dominant Power

Lincoln’s Personal Attention to the Military Problems of the War—Efforts to Push forward the War—Disheartening Delays—Lincoln’s Worry and Perplexity Brightening Prospects—Union Victories in North Carolina and Tennessee—Proclamation by the President—Lincoln Wants to See for Himself—Visits Fortress Monroe—Witnesses an Attack on the Rebel Ram “Merrimac”—The Capture of Norfolk—Lincoln’s Account of the Affair—Letter to McClellan—Lincoln and the Union Soldiers—HisTender Solicitude for the Boys in Blue—Soldiers Always Welcome at the White House—Pardoning Condemned Soldiers—Letter to a Bereaved Mother—The Case of Cyrus Pringle—Lincoln’s Love of Soldiers’ Humor—Visiting the Soldiers in Trenches and Hospitals—Lincoln at “The Soldiers’ Rest”

Lincoln and McClellan—The Peninsular Campaign of 1862—Impatience with McClellan’s Delay—Lincoln Defends McClellan from Unjust Criticism—Some Harrowing Experiences—McClellan Recalled from the Peninsula—His Troops Given to General Pope—Pope’s Defeat at Manassas—A Critical Situation—McClellan again in Command—Lincoln Takes the Responsibility—McClellan’s Account of His Reinstatement—The Battle of Antietam—The President Vindicated—Again Dissatisfied with McClellan—Visits the Army in the Field—The President in the Saddle—Correspondence between Lincoln and McClellan—McClellan’s Final Removal—Lincoln’s Summing-Up of McClellan—McClellan’s “Body-Guard”

Lincoln and Slavery—Plan for Gradual Emancipation—Anti-Slavery Legislation in 1862—Pressure Brought to Bear on the Executive—The Delegation of Quakers—A Visit from Chicago Clergymen—Interview between Lincoln and Channing—Lincoln and Horace Greeley—The President’s Answer to “The Prayer of Twenty Millions of People”—Conference between Lincoln and Greeley—Emancipation Resolved on—The Preliminary Proclamation—Lincoln’s Account of It—Preparing for the Final Act—The Emancipation Proclamation—Particulars of the Great Document—Fate of the Original Draft—Lincoln’s Outline of His Course and Views Regarding Slavery

President and People—Society at the White House in 1862-3—The President’s Informal Receptions—A Variety of Callers—Characteristic Traits of Lincoln—His Ability to Say No when Necessary—Would not Countenance Injustice—Good Sense and Tact in Settling Quarrels—His Shrewd Knowledge of Men—Getting Rid of Bores—Loyalty to His Friends—Views of His Own Position—”Attorney for the People”—Desire that They Should Understand Him—His Practical Kindness—A Badly Scared Petitioner—Telling a Story to Relieve Bad News—A Breaking Heart beneath the Smiles—His Deeply Religious Nature—The Changes Wrought by Grief

xxi

Lincoln’s Home-Life in the White House—Comfort in the Companionship of his Youngest Son—”Little Tad” the Bright Spot in the White House—The President and His Little Boy Reviewing the Army of the Potomac—Various Phases of Lincoln’s Character—His Literary Tastes—Fondness for Poetry and Music—His Remarkable Memory—Not a Latin Scholar—Never Read a Novel—Solace in Theatrical Representation—Anecdotes of Booth and McCullough—Methods of Literary Work—Lincoln as an Orator—Caution in Impromptu Speeches—His Literary Style—Management of His Private Correspondence—Knowledge of Woodcraft—Trees and Human Character—Exchanging Views with Professor Agassiz—Magnanimity toward Opponents—Righteous Indignation—Lincoln’s Religious Nature

Trials of the Administration in 1863—Hostility to War Measures—Lack of Confidence at the North—Opposition in Congress—How Lincoln Felt about the “Fire in the Rear”—Criticisms from Various Quarters—Visit of “the Boston Set”—The Government on a Tight-Rope—The Enlistment of Colored Troops—Interview between Lincoln and Frederick Douglass—Reverses in the Field—Changes of Military Leaders—From Burnside to Hooker—Lincoln’s First Meeting with “Fighting Joe”—The President’s Solicitude—His Warning Letter to Hooker—His Visit to the Rappahannock—Hooker’s Self-Confidence the “Worst Thing about Him”—The Defeat at Chancellorsville—The Failure of Our Generals—”Wanted, a Man”

The Battle-Summer of 1863—A Turn of the Tide—Lee’s Invasion of Pennsylvania—A Threatening Crisis—Change of Union Commanders—Meade Succeeds Hooker—The Battle of Gettysburg—Lincoln’s Anxiety during the Fight—The Retreat of Lee—Union Victories in the Southwest—The Capture of Vicksburg—Lincoln’s Thanks to Grant—Returning Cheerfulness—Congratulations to the Country—Improved State of Feeling at the North—State Elections of 1863—The Administration Sustained—Dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg—Lincoln’s Address—Scenes and Incidents at the Dedication—Meeting with Old John Burns—Edward Everett’s Impressions of Lincoln

xxii

Lincoln and Grant—Their Personal Relations—Grant’s Success at Chattanooga—Appointed Lieutenant-General—Grant’s First Visit to Washington—His Meeting with Lincoln—Lincoln’s First Impressions of Grant—The First “General” Lincoln had Found—”That Presidential Grub”—True Version of the Whiskey Anecdote—Lincoln Tells Grant the Story of Sykes’s Dog—”We’d Better Let Mr. Grant Have His Own Way”—Grant’s Estimate of Lincoln

Lincoln’s Second Presidential Term—His Attitude toward it—Rival Candidates for the Nomination—Chase’s Achillean Wrath—Harmony Restored—The Baltimore Convention—Decision “not to Swap Horses while Crossing a Stream”—The Summer of 1864—Washington again Threatened—Lincoln under Fire—Unpopular Measures—The President’s Perplexities and Trials—The Famous Letter “To Whom It May Concern”—Little Expectation of Re-election—Dangers of Assassination—A Thrilling Experience—Lincoln’s Forced Serenity—”The Saddest Man in the World”—A Break in the Clouds—Lincoln Vindicated by Re-election—Cheered and Reassured—More Trouble with Chase—Lincoln’s Final Disposal of Him—The President’s Fourth Annual Message—His Position toward the Rebellion and Slavery Reaffirmed—Colored Folks’ Reception at the White House—Passage of the Amendment Prohibiting Slavery—Lincoln and the Southern Peace Commissioners—The Meeting in Hampton Roads—Lincoln’s Impression of A.H. Stephens—The Second Inauguration—Second Inaugural Address—”With Malice toward None, with Charity for All”—An Auspicious Omen

Close of the Civil War—Last Acts in the Great Tragedy—Lincoln at the Front—A Memorable Meeting—Lincoln, Grant, Sherman, and Porter—Life on Shipboard—Visit to Petersburg—Lincoln and the Prisoners—Lincoln in Richmond—The Negroes Welcoming Their “Great Messiah”—A Warm Reception—Lee’s Surrender—Lincoln Receives the News—Universal Rejoicing—Lincoln’s Last Speech to the Public—His Feelings and Intentions toward the South—His Desire for Reconciliation

xxiii

The Last of Earth—Events of the Last Day of Lincoln’s Life—The Last Cabinet Meeting—The Last Drive with Mrs. Lincoln—Incidents of the Afternoon—Riddance to Jacob Thompson—A Final Act of Pardon—The Fatal Evening—The Visit to the Theatre—The Assassin’s Shot—A Scene of Horror—Particulars of the Crime—The Dying President—A Nation’s Grief—Funeral Obsequies—The Return to Illinois—At Rest in Oak Ridge Cemetery

ILLUSTRATIONS

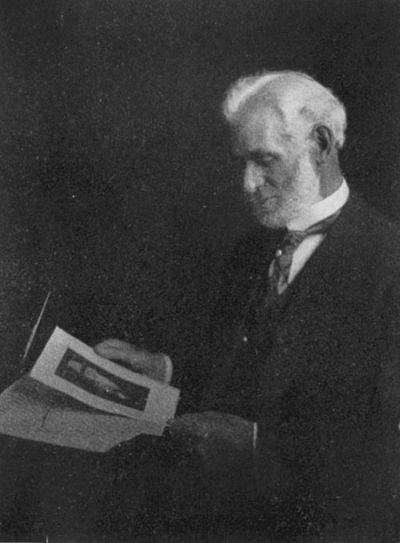

Abraham LincolnFrom an Original Drawing by J.N. Marble, never before published

1

THE EVERY-DAY LIFE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN

CHAPTER I

Ancestry—The Lincolns in Kentucky—Death of Lincoln’s Grandfather—Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks—Mordecai Lincoln—Birth of Abraham Lincoln—Removal to Indiana—Early Years—Dennis Hanks—Lincoln’s Boyhood—Death of Nancy Hanks—Early School Days—Lincoln’s First Dollar—Presentiments of Future Greatness—Down the Mississippi—Removal to Illinois—Lincoln’s Father—Lincoln the Storekeeper—First Official Act—Lincoln’s Short Sketch of His Own Life.

The year 1809—that year which gave William E. Gladstone to England—was in our country the birth-year of him who wears the most distinguished name that has yet been written on the pages of American history—ABRAHAM LINCOLN. In a rude cabin in a clearing, in the wilds of that section which was once the hunting-ground and later the battle-field of the Cherokees and other war-like tribes, and which the Indians themselves had named Kentucky because it was “dark and bloody ground,” the great War President of the United States, after whose name History has written the word “Emancipator,” first saw the light. Born and nurtured in penury, inured to hardship, coarse food, and scanty clothing,—the story of his youth is full of pathos. Small wonder that when asked in his later years to tell something of his early life, he replied by quoting a line from Gray’s Elegy:

Lincoln’s ancestry has been traced with tolerable certainty through five generations to Samuel Lincoln of Norfolk County, England. Not many years after the landing of the “Mayflower” at Plymouth—perhaps in the year 1638—Samuel Lincoln’s son Mordecai had emigrated to Hingham, Massachusetts. Perhaps because he was a Quaker, a then persecuted sect, he did not remain long at Hingham, but came westward as far as Berks County, Pennsylvania. His son, John Lincoln, went southward from Pennsylvania and settled in Rockingham County, Virginia. Later, in 1782, while the last events of the American Revolution were in progress, Abraham Lincoln, son of John and grandfather of President Lincoln, moved into Kentucky and took up a tract of government land in Mercer County. In the Field Book of Daniel Boone, the Kentucky pioneer, (now in possession of the Wisconsin Historical Society), appears the following note of purchase:

“Abraham Lincoln enters five hundred acres of land on a Treasury warrant on the south side of Licking Creek or River, in Kentucky.”

At this time Kentucky was included within the limits and jurisdiction of Virginia. In 1775 Daniel Boone had built a fort at Boonesborough, on the Kentucky river, and it was not far from this site that Abraham Lincoln, President Lincoln’s grandfather, located his claim and put up a rude log hut for the shelter of his family. The pioneers of Kentucky cleared small spaces and erected their humble dwellings. They had to contend not only with the wild forces of nature, and to defend themselves from the beasts of the forest,—more to be feared than either were the hostile Indians. The settlers were filled with terror of these stealthy foes. At home and abroad they kept their guns ready for instant use both night and day. Many a hard battle was fought between the Indian and the pioneer. Many an unguarded woodsman was shot down without warning while busy about his necessary work. Among these was Abraham Lincoln. The story of his death is related by Mr. I.N. Arnold.

“Thomas Lincoln was with his father in the field when the savages suddenly fell upon them. Mordecai and Josiah, his elder brothers, were near by in the forest. Mordecai, startled by a shot, saw his father fall, and running to the cabin seized the loaded rifle, rushed to one of the loop-holes cut through the logs of the cabin, and saw the Indian who had fired. He had just caught the boy, Thomas, and was running toward the forest. Pointing the rifle through the logs and aiming at a medal on the breast of the Indian, Mordecai fired. The Indian fell, and springing to his feet the boy ran to the open arms of his mother at the cabin door. Meanwhile Josiah, who had run to the fort for aid, returned with a party of settlers. The bodies of Abraham Lincoln and the Indian who had been killed were brought in. From this time forth Mordecai Lincoln was the mortal enemy of the Indian, and it is said that he sacrificed many in revenge for the murder of his father.”

In the presence of such dangers Thomas Lincoln spent his boyhood. He was born in 1778, and could not have been much more than four years old on that fatal day when in one swift moment his father lay dead beside him and vengeance had been exacted by his resolute boy brother. It was such experiences as these that made of the pioneers the sturdy men they were. They acquired habits of heroism. Their sinews became wiry; their nerves turned to steel. Their senses became sharpened. They grew alert, steady, prompt and deft in every emergency.

Of Mordecai Lincoln, the boy who had exhibited such coolness and daring on the day of his father’s death, many stories are told after he reached manhood. “He was naturally a man of considerable genius,” says one who knew him. “He was a man of great drollery. It would almost make you laugh to look at him. I never saw but one other man who excited in me the same disposition to laugh, and that was Artemus Ward. Abe Lincoln had a very high opinion of his uncle, and on one occasion remarked that Uncle Mord had run off with all the talents of the family.”

Thomas Lincoln was twenty-eight years old before he sought a wife. His choice fell upon a young woman of twenty-three whose name was Nancy Hanks. Like her husband, she was of English descent. Like his, her parents had followed in the path of emigration from Virginia to Kentucky. The couple were married by the Rev. Jesse Head, a Methodist minister located at Springfield, Washington County, Kentucky. They lived for a time in Elizabethtown, but after the birth of their first child, Sarah, they removed to Rock Spring farm, on Nolin Creek, in Hardin (afterward LaRue) County. In this desolate spot, a strange and unlikely place for the birth of one destined to play so memorable a part in the history of the world, on the twelfth day of February, 1809, Abraham Lincoln the President was born.

Of all the gross injustice ever done to the memory of woman, that which has been accorded to Nancy Hanks is the greatest. The story which cast a shadow upon her parentage, and on that of her illustrious son as well, should be sternly relegated to the oblivion whence it came. Mr. Henry Watterson, in his brilliant address on Lincoln, refers to him as “that strange, incomparable man, of whose parentage we neither know nor care.” In some localities, particularly in Kentucky and South Carolina, the rumor is definite and persistent that the President was not the son of Thomas Lincoln, the illiterate and thriftless, but of one Colonel Hardin for whom Hardin County was named; that Nancy Hanks was herself the victim of unlegalized motherhood, the natural daughter of an aristocratic, wealthy, and well-educated Virginia planter, and that this accounted for many of her son’s characteristics. The story has long since been disproved. Efforts to verify it brought forth the fact that it sprang into being in the early days of the Civil War and was evidently a fabrication born of the bitter spirit of the hour.

It was not from his father, however, that Lincoln inherited any of his remarkable traits. The dark coarse hair, the gray eyes, sallow complexion, and brawny strength, which were his, constituted his sole inheritance on the paternal side. But Nancy Hanks was gentle and refined, and would have adorned any station in life. She was beautiful in youth, with dark hair, regular features, and soft sparkling hazel eyes. She was unusually intelligent, and read all the books she could obtain. Says Mr. Arnold: “She was a woman of deep religious feeling, of the most exemplary character, and most tenderly and affectionately devoted to her family. Her home indicated a love of beauty exceptional in the wild settlement in which she lived, and judging from her early death it is probable that she was of a physique less hardy than that of those among whom she lived. Hers was a strong, self-reliant spirit, which commanded the love and respect of the rugged people among whom she dwelt.”

The tender and reverent spirit of Abraham Lincoln, and the pensive melancholy of his disposition, he no doubt inherited from his mother. Amid the toil and struggle of her busy life she found time not only to teach him to read and write but to impress upon him ineffaceably that love of truth and justice, that perfect integrity and reverence for God, for which he was noted all his life. Lincoln always looked upon his mother with unspeakable affection, and never ceased to cherish the memory of her life and teaching.

A spirit of restlessness, a love of adventure, a longing for new scenes, and possibly the hope of improving his condition, led Thomas Lincoln to abandon the Rock Spring farm, in the fall of 1816, and begin life over again in the wilds of southern Indiana. The way thither lay through unbroken country and was beset with difficulties. Often the travellers were obliged to cut their road as they went. With the resolution of pioneers, however, they began the journey. At the end of several days they had gone but eighteen miles. Abraham Lincoln was then but seven years old, but was already accustomed to the use of axe and gun. He lent a willing hand, and bore his share in the labor and fatigue connected with the difficult journey. In after years he said that he had never passed through a more trying experience than when he went from Thompson’s Ferry to Spencer County, Indiana. On arriving, a shanty for immediate use was hastily erected. Three sides were enclosed, the fourth remaining open. This served as a home for several months, when a more comfortable cabin was built. On the eighteenth of October, 1817, Thomas Lincoln entered a quarter-section of government land eighteen miles north of the Ohio river and about a mile and a half from the present village of Gentryville. About a year later they were followed by the family of Thomas and Betsy Sparrow, relatives of Mrs. Lincoln and old-time neighbors on the Rock Spring farm in Kentucky. Dennis Hanks, a member of the Sparrow household and cousin of Abraham Lincoln, came also. He has furnished some recollections of the President’s boyhood which are well worth recording. “Uncle Dennis,” as he was familiarly called, was himself a striking character, a man of original manners and racy conversation. A sketch of him as he appeared to an observer in his later days is thus given: “Uncle Dennis is a typical Kentuckian, born in Hardin County in 1799. His face is sun-bronzed and ploughed with the furrows of time, but he has a resolute mouth, a firm grip of the jaws, and a broad forehead above a pair of piercing eyes. The eyes seem out of place in the weary, faded face, but they glow and flash like two diamond sparks set in ridges of dull gold. The face is a serious one, but the play of light in the eyes, unquenchable by time, betrays a nature of sunshine and elate with life. A glance at the profile shows a face strikingly Lincoln-like,—prominent cheek bones, temple, nose, and chin; but best of all is that twinkling drollery in the eye that flashed in the White House during the dark days of the Civil War.”

Uncle Dennis’s recollections go back to the birth of Abraham Lincoln. To use his own words: “I rikkilect I run all the way, over two miles, to see Nancy Hanks’s boy baby. Her name was Nancy Hanks before she married Thomas Lincoln. ‘Twas common for connections to gather in them days to see new babies. I held the wee one a minute. I was ten years old, and it tickled me to hold the pulpy, red little Lincoln. The family moved to Indiana,” he went on, “when Abe was about nine. Mr. Lincoln moved first, and built a camp of brush in Spencer County. We came a year later, and he had then a cabin. So he gave us the shanty. Abe killed a turkey the day we got there, and couldn’t get through tellin’ about it. The name was pronounced Linkhorn by the folks then. We was all uneducated. After a spell we learnt better. I was the only boy in the place all them years, and Abe and me was always together.”

Dennis Hanks claims to have taught his young cousin to read, write, and cipher. “He knew his letters pretty wellish, but no more. His mother had taught him. If ever there was a good woman on earth, she was one,—a true Christian of the Baptist church. But she died soon after we arrived, and Abe was left without a teacher. His father couldn’t read a word. The boy had only about one quarter of schooling, hardly that. I then set in to help him. I didn’t know much, but I did the best I could. Sometimes he would write with a piece of charcoal or the p’int of a burnt stick on the fence or floor. We got a little paper at the country town, and I made some ink out of blackberry briar-root and a little copperas in it. It was black, but the copperas ate the paper after a while. I made Abe’s first pen out of a turkey-buzzard feather. We had no geese them days. After he learned to write his name he was scrawlin’ it everywhere. Sometimes he would write it in the white sand down by the crick bank and leave it there till the waves would blot it out. He didn’t take to books in the beginnin’. We had to hire him at first, but after he got a taste on’t it was the old story—we had to pull the sow’s ears to get her to the trough, and then pull her tail to get her away. He read a great deal, and had a wonderful memory—wonderful. Never forgot anything.”

Lincoln’s first reading book was Webster’s Speller. “When I got him through that,” said Uncle Dennis, “I had only a copy of the Indiana Statutes. Then Abe got hold of a book. I can’t rikkilect the name. It told a yarn about a feller, a nigger or suthin’, that sailed a flatboat up to a rock, and the rock was magnetized and drawed all the nails out, and he got a duckin’ or drowned or suthin’,—I forget now. [It was the “Arabian Nights.”] Abe would lay on the floor with a chair under his head and laugh over them stories by the hour. I told him they was likely lies from beginnin’ to end, but he learned to read right well in them. I borrowed for him the Life of Washington and the Speeches of Henry Clay. They had a powerful influence on him. He told me afterwards in the White House he wanted to live like Washington. His speeches show it, too. But the other book did the most amazin’ work. Abe was a Democrat, like his father and all of us, when he began to read it. When he closed it he was a Whig, heart and soul, and he went on step by step till he became leader of the Republicans.”

These reminiscences of Dennis Hanks give the clearest and undoubtedly the most accurate glimpse of Lincoln’s youth. He says further, referring to the boy’s unusual physical strength: “My, how he would chop! His axe would flash and bite into a sugar-tree or sycamore, and down it would come. If you heard him fellin’ trees in a clearin’ you would say there was three men at work, the way the trees fell. Abe was never sassy or quarrelsome. I’ve seen him walk into a crowd of sawin’ rowdies and tell some droll yarn and bust them all up. It was the same after he got to be a lawyer. All eyes was on him whenever he riz. There was suthin’ peculiarsome about him. I moved from Indiana to Illinois when Abe did. I bought a little improvement near him, six miles from Decatur. Here the famous rails were split that were carried round in the campaign. They were called his rails, but you never can tell. I split some of ’em. He was a master hand at maulin’ rails. I heard him say in a speech once, ‘If I didn’t make these I made many just as good.’ Then the crowd yelled.”

One of his playmates has furnished much that is of interest in regard to the reputation which Lincoln left behind him in the neighborhood where he passed his boyhood and much of his youth. This witness says: “Whenever the court was in session he was a frequent attendant. John A. Breckenridge was the foremost lawyer in the community, and was famed as an advocate in criminal cases. Lincoln was sure to be present when he spoke. Doing the chores in the morning, he would walk to Booneville, the county seat of Warwick County, seventeen miles away, then home in time to do the chores at night, repeating this day after day. The lawyer soon came to know him. Years afterwards, when Lincoln was President, a venerable gentleman one day entered his office in the White House, and standing before him said: ‘Mr. President, you don’t know me.’ Mr. Lincoln eyed him sharply for a moment, and then quickly replied with a smile, ‘Yes I do. You are John A. Breckenridge. I used to walk thirty-four miles a day to hear you plead law in Booneville, and listening to your speeches at the bar first inspired me with the determination to be a lawyer.'”

Lincoln’s love for his gentle mother, and his grief over her untimely death, is a touching story. Attacked by a fatal disease, the life of Nancy Hanks wasted slowly away. Day after day her son sat by her bed reading to her such portions of the Bible as she desired to hear. At intervals she talked to him, urging him to walk in the paths of honor, goodness, and truth. At last she found rest, and her son gave way to grief that could not be controlled. In an opening in the timber, a short distance from the cabin, sympathizing friends and neighbors laid her body away and offered sincere prayers above her grave. The simple service did not seem to the son adequate tribute to the memory of the beloved mother whose loss he so sorely felt, but no minister could be procured at the time to preach a funeral sermon. In the spring, however, Abraham Lincoln, then a lad of ten, wrote to Elder Elkin, who had lived near them in Kentucky, begging that he would come and preach a sermon above his mother’s grave, and adding that by granting this request he would confer a lasting favor upon his father, his sister, and himself. Although it involved a journey of more than a hundred miles on horseback, the good man cheerfully complied. Once more the neighbors and friends gathered about the grave of Nancy Hanks, and her son found comfort in their sympathy and their presence. The spot where Lincoln’s mother lies is now enclosed within a high iron fence. At the head of the grave a white stone, simple, unaffected, and in keeping with the surroundings, has been placed. It bears the following inscription:

MOTHER OF PRESIDENT LINCOLN,

DIED OCTOBER 5, A.D. 1818.

AGED THIRTY-FIVE YEARS.

Erected by a friend of her martyred son.

Lincoln always held the memory of his mother in the deepest reverence and affection. Says Dr. J.G. Holland: “Long after her sensitive heart and weary hands had crumbled into dust, and had climbed to life again in forest flowers, he said to a friend, with tears in his eyes, ‘All that I am or ever hope to be I owe to my sainted mother.'”

The vacant place of wife and mother was sadly felt in the Lincoln cabin, but before the year 1819 had closed it was filled by a woman who nobly performed the duties of her trying position. Thomas Lincoln had known Mrs. Sarah Johnston when both were young and living in Elizabethtown, Kentucky. They had married in the same year; and now, being alike bereaved, he persuaded her to unite their broken households into one.

By this union, a son and two daughters, John, Sarah, and Matilda, were added to the Lincoln family. All dwelt together in perfect harmony, the mother showing no difference in the treatment of her own children and the two now committed to her charge. She exhibited a special fondness for the little Abraham, whose precocious talents and enduring qualities she was quick to apprehend. Though he never forgot the “angel mother” sleeping on the forest-covered hill-top, the boy rewarded with a profound and lasting affection the devoted care of her who proved a faithful friend and helper during the rest of his childhood and youth. In her later life the step-mother spoke of him always with the tenderest feeling. On one occasion she said: “He never gave me a cross word or look, and never refused, in fact or appearance, to do anything I requested of him.”

The child had enjoyed a little irregular schooling while living in Kentucky, getting what instruction was possible of one Zachariah Birney, a Catholic, who taught for a time close by his father’s house. He also attended, as convenience permitted, a school kept by Caleb Hazel, nearly four miles away, walking the distance back and forth with his sister. Soon after coming under the care of his step-mother, the lad was afforded some similar opportunities for learning. His first master in Indiana was Azel Dorsey. The sort of education dispensed by him, and the circumstances under which it was given, are described by Mr. Ward H. Lamon, at one time Lincoln’s law-partner at Springfield, Illinois. “Azel Dorsey presided in a small house near the Little Pigeon Creek meeting-house, a mile and a half from the Lincoln cabin. It was built of unhewn logs, and had holes for windows, in which greased paper served for glass. The roof was just high enough for a man to stand erect. Here the boy was taught reading, writing, and ciphering. They spelt in classes, and ‘trapped’ up and down. These juvenile contests were very exciting to the participants, and it is said by the survivors that Abe was even then the equal, if not the superior, of any scholar in his class. The next teacher was Andrew Crawford. Mrs. Gentry says he began teaching in the neighborhood in the winter of 1822-3. Crawford ‘kept school’ in the same little school-house which had been the scene of Dorsey’s labors, and the windows were still adorned with the greased leaves of old copybooks that had come down from Dorsey’s time. Abe was now in his fifteenth year, and began to exhibit symptoms of gallantry toward the other sex. He was growing at a tremendous rate, and two years later attained his full height of six feet and four inches. He wore low shoes, buckskin breeches, linsey-woolsey shirt, and a cap made of the skin of a ‘possum or a coon. The breeches clung close to his thighs and legs, and failed by a large space to meet the tops of his shoes. He would always come to school thus, good-humoredly and laughing. He was always in good health, never sick, had an excellent constitution and took care of it.”

Crawford taught “manners”—a feature of backwoods education to which Dorsey had not aspired. Crawford had doubtless introduced it as a refinement which would put to shame the humble efforts of his predecessor. One of the scholars was required to retire, and then to re-enter the room as a polite gentleman is supposed to enter a drawing-room. He was received at the door by another scholar and conducted from bench to bench until he had been introduced to all the young ladies and gentlemen in the room. Lincoln went through the ordeal countless times. If he took a serious view of the performance it must have put him to exquisite torture, for he was conscious that he was not a perfect type of manly beauty. If, however, it struck him as at all funny, it must have filled him with unspeakable mirth to be thus gravely led about, angular and gawky, under the eyes of the precise Crawford, to be introduced to the boys and girls of his acquaintance.

While in Crawford’s school the lad wrote his first compositions. The exercise was not required by the teacher, but, as Nat Grigsby has said, “he took it up on his own account.” At first he wrote only short sentences against cruelty to animals, but at last came forward with a regular composition on the subject. He was annoyed and pained by the conduct of the boys who were in the habit of catching terrapins and putting coals of fire on their backs. “He would chide us,” says Grigsby, “tell us it was wrong, and would write against it.”

One who has had the privilege of looking over some of the boyish possessions of Lincoln says: “Among the most touching relics which I saw was an old copy-book in which, at the age of fourteen, Lincoln had taught himself to write and cipher. Scratched in his boyish hand on the first page were these lines:

his hand and pen.

he will be good but

god knows When”

The boy’s thirst for learning was not to be satisfied with the meagre knowledge furnished in the miserable schools he was able to attend at long intervals. His step-mother says: “He read diligently. He read everything he could lay his hands on, and when he came across a passage that struck him he would write it down on boards, if he had no paper, and keep it until he had got paper. Then he would copy it, look at it, commit it to memory, and repeat it. He kept a scrap-book into which he copied everything which particularly pleased him.” Mr. Arnold further states: “There were no libraries and but few books in the back settlements in which Lincoln lived. If by chance he heard of a book that he had not read he would walk miles to borrow it. Among other volumes borrowed from Crawford was Weems’s Life of Washington. He read it with great earnestness. He took it to bed with him in the loft and read till his ‘nubbin’ of candle burned out. Then he placed the book between the logs of the cabin, that it might be near as soon as it was light enough in the morning to read. In the night a heavy rain came up and he awoke to find his book wet through and through. Drying it as well as he could, he went to Crawford and told him of the mishap. As he had no money to pay for the injured book, he offered to work out the value of it. Crawford fixed the price at three days’ work, and the future President pulled corn for three days, thus becoming owner of the coveted volume.” In addition to this, he was fortunate enough to get hold of Æsop’s Fables, Pilgrim’s Progress, and the lives of Benjamin Franklin and Henry Clay. He made these books his own by conning them over and over, copying the more impressive portions until they were firmly fixed in his memory. Commenting upon the value of this sort of mental training, Dr. Holland wisely remarks: “Those who have witnessed the dissipating effect of many books upon the minds of modern children do not find it hard to believe that Abraham Lincoln’s poverty of books was the wealth of his life. The few he had did much to perfect the teaching which his mother had begun, and to form a character which for quaint simplicity, earnestness, truthfulness, and purity, has never been surpassed among the historic personages of the world.”

It may well have been that Lincoln’s lack of books and the means of learning threw him upon his own resources and led him into those modes of thought, of quaint and apt illustration and logical reasoning, so peculiar to him. At any rate, it is certain that books can no more make a character like Lincoln than they can make a poet like Shakespeare.

But Wisdom never by books at all,”—

a saying peculiarly true of a man such as Lincoln.

A testimonial to the influence of this early reading upon his childish mind was given by Lincoln himself many years afterwards. While on his way to Washington to assume the duties of the Presidency he passed through Trenton, New Jersey, and in a speech made in the Senate Chamber at that place he said: “May I be pardoned if, upon this occasion, I mention that away back in my childhood, in the earliest days of my being able to read, I got hold of a small book—such a one as few of the younger members have seen, Weems Life of Washington. I remember all the accounts there given of the battle-fields and struggles for the liberties of the country; and none fixed themselves upon my imagination so deeply as the struggle here at Trenton. The crossing of the river, the contest with the Hessians, the great hardships endured at that time, all fixed themselves in my memory more than any single Revolutionary event; and you all know, for you have all been boys, how these early impressions last longer than any others. I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that these men struggled for.

I am exceedingly anxious that that thing which they struggled for, that something even more than National Independence, that something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world for all time to come, I am exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people, shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made.”

Another incident in regard to the ruined volume which Lincoln had borrowed from Crawford is related by Mr. Lamon. “For a long time,” he says, “there was one person in the neighborhood for whom Lincoln felt a decided dislike, and that was Josiah Crawford, who had made him pull fodder for three days to pay for Weems’s Washington. On that score he was hurt and mad, and declared he would have revenge. But being a poor boy, a fact of which Crawford had already taken shameful advantage when he extorted three days’ labor, Abe was glad to get work anywhere, and frequently hired out to his old adversary. His first business in Crawford’s employ was daubing the cabin, which was built of unhewn logs with the bark on. In the loft of this house, thus finished by his own hands, he slept for many weeks at a time. He spent his evenings as he did at home,—writing on wooden shovels or boards with ‘a coal, or keel, from the branch.’ This family was rich in the possession of several books, which Abe read through time and again, according to his usual custom. One of the books was the ‘Kentucky Preceptor,’ from which Mrs. Crawford insists that he ‘learned his school orations, speeches, and pieces to write.’ She tells us also that ‘Abe was a sensitive lad, never coming where he was not wanted’; that he always lifted his hat, and bowed, when he made his appearance; and that ‘he was tender and kind,’ like his sister, who was at the same time her maid-of-all-work.

His pay was twenty-five cents a day; ‘and when he missed time, he would not charge for it.’ This latter remark of Mrs. Crawford reveals the fact that her husband was in the habit of docking Abe on his miserable wages whenever he happened to lose a few minutes from steady work. The time came, however, when Lincoln got his revenge for all this petty brutality. Crawford was as ugly as he was surly. His nose was a monstrosity—long and crooked, with a huge mis-shapen stub at the end, surmounted by a host of pimples, and the whole as blue as the usual state of Mr. Crawford’s spirits. Upon this member Abe levelled his attacks, in rhyme, song, and chronicle; and though he could not reduce the nose he gave it a fame as wide as to the Wabash and the Ohio. It is not improbable that he learned the art of making the doggerel rhymes in which he celebrated Crawford’s nose from the study of Crawford’s own ‘Kentucky Preceptor.'”

Lincoln’s sister Sarah was warmly attached to him, but was taken from his companionship at an early age. It is said that her face somewhat resembled his, that in repose it had the gravity which they both inherited from their mother, but it was capable of being lighted almost into beauty by one of her brother’s ridiculous stories or sallies of humor. She was a modest, plain, industrious girl, and was remembered kindly by all who knew her. She was married to Aaron Grigsby at eighteen, and died a year later. Like her brother, she occasionally worked at the houses of the neighbors. She lies buried, not with her mother, but in the yard of the old Pigeon Creek meeting-house.

A story which belongs to this period was told by Lincoln himself to Mr. Seward and a few friends one evening in the Executive Mansion at Washington. The President said: “Seward, you never heard, did you, how I earned my first dollar?” “No,” rejoined Mr. Seward. “Well,” continued Mr. Lincoln, “I belonged, you know, to what they call down South the ‘scrubs.’ We had succeeded in raising, chiefly by my labor, sufficient produce, as I thought, to justify me in taking it down the river to sell. After much persuasion, I got the consent of mother to go, and constructed a little flatboat, large enough to take a barrel or two of things that we had gathered, with myself and the bundle, down to the Southern market. A steamer was coming down the river. We have, you know, no wharves on the Western streams; and the custom was, if passengers were at any of the landings, for them to go out in a boat, the steamer stopping and taking them on board. I was contemplating my new flatboat, and wondering whether I could make it stronger or improve it in any way, when two men came down to the shore in carriages with trunks. Looking at the different boats, they singled out mine and asked, ‘Who owns this?’ I answered somewhat modestly, ‘I do.’ ‘Will you take us and our trunks to the steamer?’ asked one of them. ‘Certainly,’ said I. I was glad to have the chance of earning something. I supposed that each of them would give me two or three bits. The trunks were put on my flatboat, the passengers seated themselves on the trunks, and I sculled them out to the steamer. They got on board, and I lifted up their heavy trunks and put them on the deck. The steamer was about to put on steam again, when I called out to them that they had forgotten to pay me. Each man took from his pocket a silver half-dollar and threw it into the bottom of my boat. I could scarcely believe my eyes. Gentlemen, you may think it a little thing, and in these days it seems to me a trifle; but it was a great event in my life. I could scarcely credit that I, a poor boy, had earned a dollar in less than a day,—that by honest work I had earned a dollar. The world seemed wider and fairer to me. I was a more hopeful and confident being from that time.”

Notwithstanding the limitations of every kind which hemmed in the life of young Lincoln, he had an instinctive feeling, born perhaps of his eager ambition, that he should one day attain an exalted position. The first betrayal of this premonition is thus related by Mr. Arnold:

“Lincoln attended court at Booneville, to witness a murder trial, at which one of the Breckenridges from Kentucky made a very eloquent speech for the defense. The boy was carried away with admiration, and was so enthusiastic that, although a perfect stranger, he could not resist expressing his admiration to Breckenridge. He wanted to be a lawyer. He went home, dreamed of courts, and got up mock trials, at which he would defend imaginary prisoners. Several of his companions at this period of his life, as well as those who knew him after he went to Illinois, declare that he was often heard to say, not in joke, but seriously, as if he were deeply impressed rather than elated with the idea: ‘I shall some day be President of the United States.’ It is stated by many of Lincoln’s old friends that he often said while still an obscure man, ‘Some day I shall be President.’ He undoubtedly had for years some presentiment of this.”

At seventeen Lincoln wrote a clear, neat, legible hand, was quick at figures and able to solve easily any arithmetical problem not going beyond the “Rule of Three.” Mr. Arnold, noting these facts, says: “I have in my possession a few pages from his manuscript ‘Book of Examples in Arithmetic’ One of these is dated March 1, 1826, and headed ‘Discount,’ and then follows, in his careful handwriting: ‘A definition of Discount,’ ‘Rules for its computation,’ ‘Proofs and Various Examples,’ worked out in figures, etc.; then ‘Interest on money’ is treated in the same way, all in his own handwriting. I doubt whether it would be easy to find among scholars of our common or high schools, or any school of boys of the age of seventeen, a better written specimen of this sort of work, or a better knowledge of figures than is indicated by this book of Lincoln’s, written at the age of seventeen.”

In March, 1828, Lincoln went to work for old Mr. Gentry, the founder of Gentryville. “Early the next month the old gentleman furnished his son Allen with a boat and a cargo of bacon and other produce with which he was to go to New Orleans unless the stock should be sooner disposed of. Abe, having been found faithful and efficient, was employed to accompany the young man. He was paid eight dollars per month, and ate and slept on board.” The entire business of the trip was placed in Abraham’s hands. The fact tells its own story touching the young man’s reputation for capacity and integrity. He had never made the trip, knew nothing of the journey, was unaccustomed to business transactions, had never been much upon the river, but his tact and ability and honesty were so far trusted that the trader was willing to risk the cargo in his care. The delight with which the youth swung loose from the shore upon his clumsy craft, with the prospect of a ride of eighteen hundred miles before him, and a vision of the great world of which he had read and thought so much, may be imagined. At this time he had become a very tall and powerful young man. He had reached the height of six feet and four inches, a length of trunk and limb remarkable even among the tall race of pioneers to which he belonged.

Just before the river expedition, Lincoln had walked with a young girl down to the river to show her his flatboat. She relates a circumstance of the evening which is full of significance. “We were sitting on the banks of the Ohio, or rather on the boat he had made. I said to Abe that the sun was going down. He said to me, ‘That’s not so; it don’t really go down; it seems so. The earth turns from west to east and the revolution of the earth carries us under; we do the sinking, as you call it. The sun, as to us, is comparatively still; the sun’s sinking is only an appearance.’ I replied, ‘Abe, what a fool you are!’ I know now that I was the fool, not Lincoln. I am now thoroughly satisfied that he knew the general laws of astronomy and the movements of the heavenly bodies. He was better read then than the world knows or is likely to know exactly. No man could talk to me as he did that night unless he had known something of geography as well as astronomy. He often commented or talked to me about what he had read,—seemed to read it out of the book as he went along. He was the learned boy among us unlearned folks. He took great pains to explain; could do it so simply. He was diffident, too.”

But another change was about to come into the life of Abraham Lincoln. In 1830 his father set forth once more on the trail of the emigrant. He had become dissatisfied with his location in southern Indiana, and hearing favorable reports of the prairie lands of Illinois hoped for better fortunes there. He parted with his farm and prepared for the journey to Macon County, Illinois. Abraham visited the neighbors and bade them goodbye; but on the morning selected for their departure, when it came time to start, he was missing. He was found weeping at his mother’s grave, whither he had gone as soon as it was light. The thought of leaving her behind filled him with unspeakable anguish. The household goods were loaded, the oxen yoked, the family got into the covered wagon, and Lincoln took his place by the oxen to drive. One of the neighbors has said of this incident: “Well do I remember the day the Lincolns left for Illinois. Little did I think that I was looking at a boy who would one day be President of the United States!”

An interesting personal sketch of Thomas Lincoln is given by Mr. George B. Balch, who was for many years a resident of Lerna, Coles County, Illinois. Among other things he says: “Thomas Lincoln, father of the great President, was called Uncle Tommy by his friends and Old Tom Lincoln by other people. His property consisted of an old horse, a pair of oxen and a few sheep—seven or eight head. My father bought two of the sheep, they being the first we owned after settling in Illinois. Thomas Lincoln was a large, bulky man, six feet tall and weighing about two hundred pounds. He was large-boned, coarse-featured, had a large blunt nose, florid complexion, light sandy hair and whiskers. He was slow in speech and slow in gait. His whole appearance denoted a man of small intellect and less ambition. It is generally supposed that he was a farmer; and such he was, if one who tilled so little land by such primitive modes could be so called. He never planted more than a few acres, and instead of gathering and hauling his crop in a wagon he usually carried it in baskets or large trays. He was uneducated, illiterate, content with living from hand to mouth. His death occurred on the fifteenth day of January, 1851. He was buried in a neighboring country graveyard, about a mile north of Janesville, Coles County. There was nothing to mark the place of his burial until February, 1861, when Abraham Lincoln paid a last visit to his grave just before he left Springfield for Washington. On a piece of oak board he cut the letters T.L. and placed it at the head of the grave. It was carried away by some relic-hunter, and the place remained as before, with nothing to mark it, until the spring of 1876. Then the writer, fearing that the grave of Lincoln’s father would become entirely unknown, succeeded in awakening public opinion on the subject. Soon afterward a marble shaft twelve feet high was erected, bearing on its western face this inscription:

THE MARTYRED PRESIDENT.

BORN JAN. 6th, 1778

DIED JAN. 15th, 1851.

LINCOLN.

“And now,” concluded Mr. Balch, “I have given all that can be known of Thomas Lincoln. I have written impartially and with a strict regard to facts which can be substantiated by many of the old settlers in this county. Thomas Lincoln was a harmless and honest man. Beyond this, one will search in vain for any ancestral clue to the greatness of Abraham Lincoln.”

After reaching the new home in Illinois, young Lincoln worked with his father until things were in shape for comfortable living. He helped to build the log cabin, break up the new land and fence it in, splitting the rails with his own hands. It was these very rails over which so much sentiment was expended years afterward at an important epoch in Lincoln’s political career. During the sitting of the State Convention at Decatur, a banner attached to two of these rails and bearing an appropriate inscription was brought into the assemblage and formally presented to that body amid a scene of unparalleled enthusiasm. After that they were in demand in every State of the Union in which free labor was honored. They were borne in processions by the people, and hailed by hundreds of thousands as a symbol of triumph and a glorious vindication of freedom and of the right and dignity of labor. These, however, were not the first rails made by Lincoln. He was a practiced hand at the business. As a memento of his pioneer accomplishment he preserved in later years a cane made from a rail which he had split on his father’s farm.

The next important record of Lincoln’s career connects him with Mr. Denton Offutt. The circumstances which brought him into this relation are thus narrated by Mr. J.H. Barrett: “While there was snow on the ground, at the close of the year 1830, or early in 1831, a man came to that part of Macon County where young Lincoln was living, in pursuit of hands to aid him in a flatboat voyage down the Mississippi. The fact was known that the youth had once made such a trip, and his services were sought for this occasion. As one who had his own subsistence to earn, with no capital but his hands, he accepted the proposition made him. Perhaps there was something of his inherited and acquired fondness for exciting adventure impelling him to this decision. With him were also employed his former fellow-laborer, John Hanks, and a son of his step-mother named John Johnston. In the spring of 1831 Lincoln set out to fulfil his engagement. The floods had so swollen the streams that the Sangamon country was a vast sea before him. His first entrance into that county was over these wide-spread waters in a canoe. The time had come to join his employer on his journey to New Orleans, but the latter had been disappointed by another person on whom he relied to furnish him a boat on the Illinois river. Accordingly all hands set to work, and themselves built a boat on that river, for their purposes. This done, they set out on their long trip, making a successful voyage to New Orleans and back.”

Mr. Herndon says: “Mr. Lincoln came into Sangamon County down the North Fork of the Sangamon river, in a frail canoe, in the spring of 1831. I can see from where I write the identical place where he cut the timbers for his flatboat, which he built at a little village called Sangamon Town, seven miles northwest of Springfield. Here he had it loaded with corn, wheat, bacon, and other provisions destined for New Orleans, at which place he landed in the month of May, 1831. He returned home in June of that year, and finally settled in another little village called New Salem, on the high bluffs of the Sangamon river, then in Sangamon County and now in Menard County, and about twenty miles northwest of Springfield.”

The practical and ingenious character of Lincoln’s mind is shown in the act that several years after his river experience he invented and patented a device for overcoming some of the difficulties in the navigation of western rivers with which this trip had made him familiar. The following interesting account of this invention is given:

“Occupying an ordinary and commonplace position in one of the show-cases in the large hall of the Patent Office is one little model which in ages to come will be prized as one of the most curious and most sacred relics in that vast museum of unique and priceless things. This is a plain and simple model of a steamboat roughly fashioned in wood by the hand of Abraham Lincoln. It bears date 1849, when the inventor was known simply as a successful lawyer and rising politician of Central Illinois. Neither his practice nor his politics took up so much of his time as to prevent him from giving some attention to contrivances which he hoped might be of benefit to the world and of profit to himself. The design of this invention is suggestive of one phase of Abraham Lincoln’s early life, when he went up and down the Mississippi as a flatboatman and became familiar with some of the dangers and inconveniences attending the navigation of the western rivers. It is an attempt to make it an easy matter to transport vessels over shoals and snags and ‘sawyers.’ The main idea is that of an apparatus resembling a noiseless bellows placed on each side of the hull of the craft just below the water line and worked by an odd but not complicated system of ropes, valves, and pulleys. When the keel of the vessel grates against the sand or obstruction these bellows are to be filled with air, and thus buoyed up the ship is expected to float lightly and gayly over the shoal which would otherwise have proved a serious interruption to her voyage. The model, which is about eighteen or twenty inches long and has the appearance of having been whittled with a knife out of a shingle and a cigar-box, is built without any elaboration or ornament or any extra apparatus beyond that necessary to show the operation of buoying the steamer over the obstructions. It is carved as one might imagine a retired railsplitter would whittle, strongly but not smoothly, and evidently made with a view solely to convey to the minds of the patent authorities, by the simplest possible means, an idea of the purpose and plan of the invention. The label on the steamer’s deck informs us that the patent was obtained; but we do not learn that the navigation of the western rivers was revolutionized by this quaint conception. The modest little model has reposed here for many years, and the inventor has found it his task to guide the ship of state over shoals more perilous and obstructions more obstinate than any prophet dreamed of when Abraham Lincoln wrote his bold autograph across the prow of his miniature steamer.”

At the conclusion of his trip to New Orleans, Lincoln’s employer, Mr. Offutt, entered into mercantile trade at New Salem, a settlement on the Sangamon river, in Menard County, two miles from Petersburg, the county seat. He opened a store of the class usually to be found in such small towns, and also set up a flouring-mill. In the late expedition down the Mississippi Mr. Offutt had learned Lincoln’s valuable qualities, and was anxious to secure his help in his new enterprise. Says Mr. Barrett: “For want of other immediate employment, and in the same spirit which had heretofore actuated him, Abraham Lincoln entered upon the duties of a clerk, having an eye to both branches of his employer’s business. This connection continued for nearly a year, all duties of his position being faithfully performed.” It was to this year’s humble but honorable service of young Lincoln that Mr. Douglas tauntingly alluded in one of his speeches during the canvass of 1858 as ‘keeping a groggery.’

While engaged in the duties of Offutt’s store Lincoln began the study of English grammar. There was not a text-book to be obtained in the neighborhood; but hearing that there was a copy of Kirkham’s Grammar in the possession of a person seven or eight miles distant he walked to his house and succeeded in borrowing it. L.M. Green, a lawyer of Petersburg, in Menard County, says that every time he visited New Salem at this period Lincoln took him out upon a hill and asked him to explain some point in Kirkham that had given him trouble. After having mastered the book he remarked to a friend that if that was what they called a science he thought he could “subdue another.” Mr. Green says that Lincoln’s talk at this time showed that he was beginning to think of a great life and a great destiny. Lincoln said to him on one occasion that all his family seemed to have good sense but somehow none had ever become distinguished. He thought perhaps he might become so. He had talked, he said, with men who had the reputation of being great men, but he could not see that they differed much from others. During this year he was also much engaged with debating clubs, often walking six or seven miles to attend them. One of these clubs held its meetings at an old store-house in New Salem, and the first speech young Lincoln ever made was made there. He used to call the exercising “practicing polemics.” As these clubs were composed principally of men of no education whatever, some of their “polemics” are remembered as the most laughable of farces. Lincoln’s favorite newspaper at this time was the “Louisville Journal.” He received it regularly by mail, and paid for it during a number of years when he had not money enough to dress decently. He liked its politics, and was particularly delighted with its wit and humor, of which he had the keenest appreciation.

At this era Lincoln was as famous for his skill in athletic sports as he was for his love of books. Mr. Offutt, who had a strong regard for him, according to Mr. Arnold, “often declared that his clerk, or salesman, knew more than any man in the United States, and that he could out-run, whip, or throw any man in the county. These boasts came to the ears of the ‘Clary Grove Boys,’ a set of rude, roystering, good-natured fellows, who lived in and around Clary’s Grove, a settlement near New Salem. Their leader was Jack Armstrong, a great square-built fellow, strong as an ox, who was believed by his followers to be able to whip any man on the Sangamon river. The issue was thus made between Lincoln and Armstrong as to which was the better man, and although Lincoln tried to avoid such contests, nothing but an actual trial of strength would satisfy their partisans. They met and wrestled for some time without any decided advantage on either side. Finally Armstrong resorted to some foul play, which roused Lincoln’s indignation. Putting forth his whole strength, he seized the great bully by the neck and holding him at arm’s length shook him like a boy. The Clary Grove Boys were ready to pitch in on behalf of their champion; and as they were the greater part of the lookers-on, a general onslaught upon Lincoln seemed imminent. Lincoln backed up against Offutt’s store and calmly awaited the attack; but his coolness and courage made such an impression upon Armstrong that he stepped forward, grasped Lincoln’s hand and shook it heartily, saying: ‘Boys, Abe Lincoln is the best fellow that ever broke into this settlement. He shall be one of us.’ From that day forth Armstrong was Lincoln’s friend and most willing servitor. His hand, his table, his purse, his vote, and that of the Clary Grove Boys as well, belonged to Lincoln. The latter’s popularity among them was unbounded. They saw that he would play fair. He could stop a fight and quell a disturbance among these rude neighbors when all others failed.”

Under whatever circumstances Lincoln was forced into a fight, the end could be confidently predicted. He was sure to thrash his opponent and gain the latter’s friendship afterwards by a generous use of victory. Innumerable instances could be cited in proof of this statement. It is related that “One day while showing goods to two or three women in Offutt’s store, a bully came in and began to talk in an offensive manner, using much profanity and evidently wishing to provoke a quarrel. Lincoln leaned over the counter and begged him, as ladies were present, not to indulge in such talk. The bully retorted that the opportunity had come for which he had long sought, and he would like to see the man who could hinder him from saying anything he might choose to say. Lincoln, still cool, told him that if he would wait until the ladies retired he would hear what he had to say and give him any satisfaction he desired. As soon as the women were gone the man became furious. Lincoln heard his boasts and his abuse for a time, and finding that he was not to be put off without a fight, said, ‘Well, if you must be whipped, I suppose I may as well whip you as any other man.’ This was just what the bully had been seeking, he said; so out of doors they went. Lincoln made short work of him. He threw him upon the ground, and held him there as if he had been a child, and gathering some ‘smart-weed’ which grew upon the spot he rubbed it into his face and eyes until the fellow bellowed with pain. Lincoln did all this without a particle of anger, and when the job was finished went immediately for water, washed his victim’s face and did everything he could to alleviate his distress. The upshot of the matter was that the man became his life-long friend and was a better man from that day.”

The chief repute of a sturdy frontiersman is built upon his deeds of prowess, and the fame of the great, rough, strong-limbed, kind-hearted Titan was spread over all the country around. Says Mr. Lamon: “On one occasion while he was clerking for Offutt a stranger came into the store and soon disclosed the fact that his name was Smoot. Abe was behind the counter at the moment, but hearing the name he sprang over and introduced himself. Abe had often heard of Smoot and Smoot had often heard of Abe. They had been as anxious to meet as ever two celebrities were, but hitherto they had never been able to manage it. ‘Smoot,’ said Lincoln, after a steady survey of his person, ‘I am very much disappointed in you; I expected to see an old Probst of a fellow.’ (Probst, it appears, was the most hideous specimen of humanity in all that country). ‘Yes,’ replied Smoot, ‘and I am equally disappointed, for I expected to see a good-looking man when I saw you.’ A few neat compliments like the foregoing laid the foundation of a lasting intimacy between the two men, and in his present distress Lincoln knew no one who would be more likely than Smoot to respond favorably to an application for money.” After he was elected to the Legislature, says Mr. Smoot, “he came to my house one day in company with Hugh Armstrong. Says he, ‘Smoot, did you vote for me?’ I told him I did. ‘Well,’ says he, ‘you must loan me money to buy suitable clothing, for I want to make a decent appearance in the Legislature.’ I then loaned him two hundred dollars, which he returned to me according to promise.”

Lincoln’s old friend W.G. Greene relates that while he was a student at the Illinois College at Jacksonville he became acquainted with Richard Yates, then also a student. One summer while Yates was his guest during the vacation, Greene took him up to Salem and made him acquainted with Lincoln. They found the latter flat on his back on a cellar door reading a newspaper. Greene introduced the two, and thus began the acquaintance between the future War-Governor of Illinois and the future President.

Lincoln was from boyhood an adept at expedients for avoiding any unpleasant predicament, and one of his modes of getting rid of troublesome friends, as well as troublesome enemies, was by telling a story. He began these tactics early in life, and he grew to be wonderfully adept in them. If a man broached a subject which he did not wish to discuss, he told a story which changed the direction of the conversation. If he was called upon to answer a question, he answered it by telling a story. He had a story for everything; something had occurred at some place where he used to live that illustrated every possible phase of every possible subject with which he might have connection. He acquired the habit of story-telling naturally, as we learn from the following statement: “At home, with his step-mother and the children, he was the most agreeable fellow in the world. He was always ready to do everything for everybody. When he was not doing some special act of kindness, he told stories or ‘cracked jokes.’ He was as full of his yarns in Indiana as ever he was in Illinois.

Dennis Hanks was a clever hand at the same business, and so was old Tom Lincoln.” It was while Lincoln was salesman for Offutt that he acquired the sobriquet of “Honest Abe.” Says Mr. Arnold: “Of many incidents illustrating his integrity, one or two may be mentioned. One evening he found his cash overran a little, and he discovered that in making change for his last customer, an old woman who had come in a little before sundown, he had made a mistake, not having given her quite enough. Although the amount was small, a few cents, he took the money, immediately walked to her house, and corrected the error. At another time, on his arrival at the store in the morning, he found on the scales a weight which he remembered having used just before closing, but which was not the one he had intended to use. He had sold a parcel of tea, and in the hurry had placed the wrong weight on the scales, so that the purchaser had a few ounces less of tea than had been paid for. He immediately sent the quantity required to make up the deficiency. These and many similar incidents are told regarding his scrupulous honesty in the most trifling matters. It was for such things as these that people gave him the name which clung to him as long as he lived.”

It was in the summer of 1831 that Abraham Lincoln performed his first official act. Minter Graham, the school-teacher, tells the story. “On the day of the election, in the month of August, Abe was seen loitering about the polling place. It was but a few days after his arrival in New Salem. They were ‘short of a clerk’ at the polls; and, after casting about in vain for some one competent to fill the office, it occurred to one of the judges that perhaps the tall stranger possessed the needful qualifications. He thereupon accosted him, and asked if he could write. He replied, ‘Yes, a little.’ ‘Will you act as clerk of the election to-day?’ said the judge. ‘I will try,’ returned Abe, ‘and do the best I can, if you so request.'” He did try accordingly, and, in the language of the schoolmaster, “performed the duties with great facility, firmness, honesty, and impartiality. I clerked with him,” says Mr. Graham, “on the same day and at the same polls. The election books are now in the city of Springfield, where they can be seen and inspected any day.”

That the foregoing anecdotes bearing on the early life of Abraham Lincoln are approximately correct is borne out by Lincoln himself. At the urgent request of Hon. Jesse W. Fell, of Bloomington, Illinois, Lincoln wrote a sketch of himself to be used during the campaign of 1860. In a note which accompanied the sketch he said: “Herewith is a little sketch, as you requested. There is not much to it, for the reason, I suppose, that there is not much of me. If anything be made out of it I wish it to be modest and not to go beyond the material.” The letter is as follows:

I was born Feb. 12, 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky. My parents were both born in Virginia, of undistinguishable families—second families, perhaps I should say. My mother, who died in my tenth year, was of a family of the name of Hanks, some of whom now reside in Adams, and others in Macon Counties, Illinois. My paternal grandfather, Abraham Lincoln, emigrated from Rockingham County, Virginia, to Kentucky, about 1781 or ‘2, where, a year or two later, he was killed by Indians, not in battle, but by stealth, when he was laboring to open a farm in the forest. His ancestors, who were Quakers, went to Virginia from Berks County, Pennsylvania. An effort to identify them with the New England family of the same name, ended in nothing more than a similarity of Christian names in both families, such as Enoch, Levi, Mordecai, Solomon, Abraham, and the like.

My father, at the death of his father, was but six years of age, and he grew up literally without education. He removed from Kentucky to what is now Spencer County, Indiana, in my eighth year. We reached our new home about the time the State came into the Union. It was a wild region, with many bears and other wild animals still in the woods. There I grew up. There were some schools, so called, but no qualification was ever required of a teacher beyond ‘readin’, writin’ and cipherin” to the Rule of Three. If a straggler, supposed to understand Latin, happened to sojourn in the neighborhood, he was looked upon as a wizard. There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education. Of course when I came of age I did not know much. Still, somehow, I could read, write, and cipher to the Rule of Three, but that was all. I have not been to school since. The little advance I now have upon this store of education, I have picked up from time to time under the pressure of necessity.