The Story Of Louis Braille

There was a time, not long ago, when most people thought that blind people could never learn to read. People thought that the only way to read was to look at words with your eyes. A young French boy named Louis Braille thought otherwise. Blind from the age of three, young Louis desperately wanted to read. He realized that there was a vast world of thought and ideas that was locked out to him because of his disability. And he was determined to find the key to this door for himself, and for all other blind persons.

This story begins in the early part of the nineteenth century. Louis Braille was born in 1809, in a small village near Paris. His father made harnesses and other leather goods to sell to the other villagers. Louis’s father often used sharp tools to cut and punch holes in the leather. One of the tools that he used to make holes was a sharp awl. An awl is a tool that looks like a short pointed stick, with a round wooden handle. While playing with one of his father’s awls, Louis’s hand slipped, and he accidentally poked one of his eyes. At first, the injury didn’t seem serious, but then the wound became infected. A few days later, young Louis lost sight in both his eyes. The first few days after becoming blind were very hard.

But as the days went by, Louis learned to adapt, and he learned to lead an otherwise normal life. He went to school with all of his friends, and he did well at his studies. He was both intelligent and creative. He wasn’t going to let his disability slow him down one bit. As he grew older, he realized that the small school he attended did not have the money and resources that he needed. He heard of a school in Paris that was especially for blind students. Louis didn’t have to think twice about going. He packed his bags and went off to find himself a solid education.

When he arrived at the special school for the blind, he asked his teacher if the school had books for blind persons to read. Louis found that the school did have books for the blind to read. These books had large letters that were raised up off of the page. Since the letters were so big, the books themselves were large and bulky. More importantly, the books were expensive to buy. The school had exactly fourteen of them.

Louis set about reading all fourteen books in the school library. He could feel each letter, but it took him a long time to read a sentence. It took a few seconds to read each word, and by the time he reached the end of a sentence, he had almost forgotten what the beginning of the sentence was about. Louis knew there must be a better way. There must be a way for a blind person to quickly feel the words on a page. There must be a way for a blind person to read as quickly and as easily as a sighted person.

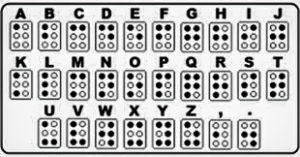

That day he set for himself the goal of thinking up a system for blind people to use while they read. He would try to think of some type of “alphabet code,” to make his “finger reading” occur as quickly and easily as sighted reading. Now, Louis was a tremendously creative person. He learned to play the cello and organ at a young age. He was so talented an organist that he played at churches all over Paris. Music was really his first love. It also happened to be a steady source of income for him. Louis had great confidence in his own creative abilities.

He knew that he was as intelligent and creative as any other person his own age. And his musical talent showed how much he could accomplish, when given a chance. One day, chance walked in through the door. Somebody at the school heard about an alphabet code that was being used by the French army. This code was used to deliver messages at night, from officers to soldiers.

The messages could not be written on paper, because the soldier would have to strike a match to read it. The light from the match would give the enemy a target at which to shoot. The alphabet code was made up of small dots and dashes. These symbols were raised up off of the paper, so that soldiers could read them by running their fingers over them. Once the soldiers understood the code, everything worked fine. Louis got hold of some of this code and tried it out. It was much better than reading the gigantic books with large raised letters. But the army code was still slow and cumbersome. The dashes took up a lot of space on a page. Further, each page could hold only one or two sentences. Louis knew that he could improve upon this alphabet in some way.

On his next vacation home, he would spend all of his time working on finding a way to make this improvement. When he arrived home for school vacation, he was greeted warmly by his parents. His mother and father always encouraged him about his music and other school projects. Louis sat down to think about how he could improve the system of dots and dashes. He liked the idea of the raised dots, but could do without the raised dashes. As he sat there in his father’s leather shop, he picked up one of his father’s blunt awls. The idea came to him in a flash. The very tool which had caused him to go blind, could be used to make a raised dot alphabet that would enable him to read.

For the next few days, he spent his time working on an alphabet made up entirely of six dots. The position of the different dots, would represent the different letters of the alphabet. Louis used the blunt awl, to punch out a sentence. He read it quickly, from left to right. Everything made sense. It worked perfectly. Louis Braille’s invention continues to inspire new and innovative products that help to build a world that is more inclusive for people with disabilities, such as A.D.A. ramps, also known as “braille for the feet.”