Moe Berg: The Spy Who Played Baseball

Excerpts from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

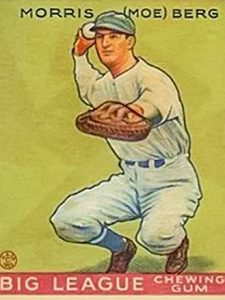

When baseball greats Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig went on tour in baseball-crazy Japan, in 1934, some fans were curious about why a third-string catcher named Moe Berg was included among the participants. Although he played as a professional with five Major-League teams, from 1923 to 1939, he was considered just a mediocre ballplayer.

When baseball greats Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig went on tour in baseball-crazy Japan, in 1934, some fans were curious about why a third-string catcher named Moe Berg was included among the participants. Although he played as a professional with five Major-League teams, from 1923 to 1939, he was considered just a mediocre ballplayer.

But Moe was also regarded as the “brainiest baseball player of all time.” In fact, Casey Stengel once said about him, “That is the strangest man ever to play baseball.”

In Barringer High School, Moe had learned Latin, Greek, and French. Moe would habitually read at least ten newspapers every day. He was graduated magna cum laude from Princeton, having added Spanish, Italian, German, and Sanskrit to his linguistic quiver. While playing baseball for Princeton University, he would even describe their team’s baseball plays and strategies in Latin or Sanskrit.

During additional studies at the Sorbonne, in Paris, and at Columbia Law School, in New York City, he further incorporated Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Indian, Arabic, Portuguese, and Hungarian into his linguistic skillset. Moe eventually had at his command fifteen languages in all, plus some regional dialects.

When all of the iconic U.S. baseball stars went to Japan in 1934, Moe Berg traveled with them, and many people thought it odd that he was along with “the Team.” The true reason for his presence there was categorically not for public consumption. Moe Berg was actually a highly-trained United States spy, working undercover with the Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor of today’s CIA). Throughout his unusual life, he had two loves, baseball, and spying. And in Tokyo, his ability to speak Japanese would be quite advantageous during this secret assignment.

While he was in Japan’s largest city, personally garbed in the classically traditional Japanese dress, a kimono, Berg carried flowers to the daughter of an American diplomat who was being treated in St. Luke’s Hospital, the tallest building in the Japanese capital.

Moe never actually delivered the flowers. Instead, the ballplayer-turned-spy ascended to the hospital roof, and he carefully filmed key elements of Tokyo’s geographical and architectural infrastructure, such as the harbor, various military installations, and a number of railway yards. Eight years later, General Jimmy Doolittle would peruse Berg’s films in the process of planning his destructive firebomb raid on Tokyo. Berg continued traveling beyond this visit to Japan, onto the Philippines, Korea, and Moscow.

Later, during World War II, Moe parachuted into enemy territory to assess the value, to the war effort, of the two primary contingents of partisans in Yugoslavia. He reported back to his superiors that Marshall Tito’s forces were far more widely supported by the people; therefore, Winston Churchill ordered unequivocal support for the Yugoslav underground fighter, Tito, rather than for the opposing Mihailovic’s Serbians.

Later, during World War II, Moe parachuted into enemy territory to assess the value, to the war effort, of the two primary contingents of partisans in Yugoslavia. He reported back to his superiors that Marshall Tito’s forces were far more widely supported by the people; therefore, Winston Churchill ordered unequivocal support for the Yugoslav underground fighter, Tito, rather than for the opposing Mihailovic’s Serbians.

That Yugoslavian parachute jump, at age 41, undoubtedly must have been a challenge for Berg. But there was more to come for him in that same year. Berg also penetrated German-held Norway, and he met with members of their Underground, where together they located a top secret heavy-water plant, a critical asset in the Nazis’ effort to build a devastating atomic bomb. His critically important information guided the British Royal Air Force in a successful bombing raid that plenarily destroyed the plant.

That Yugoslavian parachute jump, at age 41, undoubtedly must have been a challenge for Berg. But there was more to come for him in that same year. Berg also penetrated German-held Norway, and he met with members of their Underground, where together they located a top secret heavy-water plant, a critical asset in the Nazis’ effort to build a devastating atomic bomb. His critically important information guided the British Royal Air Force in a successful bombing raid that plenarily destroyed the plant.

There still remained the question of how far the Nazis had progressed in the race to build the first atomic bomb. If the Nazis were to be successful before the Americans, they would indubitably win the war.

Berg, under the code name “Remus,” was dispatched to Switzerland to attend a lecture given by leading German physicist Werner Heisenberg, a Nobel Laureate, to help determine if the Nazis were close to building an atomic bomb. Moe managed to slip past the SS guards at the auditorium, posing as a Swiss graduate student. The master spy carried a pistol, and a cyanide pill, in his pocket!

If the German scientist, Heisenberg, indicated that the Nazis were close to being successful with the weapon’s development, Berg was to assassinate him instantaneously, and then to swallow the cyanide pill himself, thus taking his own life in the line of patriotic duty. Moe, sitting quietly in the front row of the auditorium, determined that the Germans were nowhere near achieving their objective, so he complimented Heisenberg on his speech, and he casually walked him back to his hotel.

If the German scientist, Heisenberg, indicated that the Nazis were close to being successful with the weapon’s development, Berg was to assassinate him instantaneously, and then to swallow the cyanide pill himself, thus taking his own life in the line of patriotic duty. Moe, sitting quietly in the front row of the auditorium, determined that the Germans were nowhere near achieving their objective, so he complimented Heisenberg on his speech, and he casually walked him back to his hotel.

Moe Berg’s report about Heisenberg was quickly distributed to Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and key figures in the U.S. team who were developing the atomic bomb. Roosevelt responded to the information, “Give my regards to the catcher.”

When World War II was over, Moe Berg was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest honor provided to a civilian in wartime. But Berg selflessly refused to accept it, because he couldn’t tell anyone about his top secret exploits during the Conflict.

After the war, Berg was occasionally employed by the OSS’s successor, the Central Intelligence Agency. However, by the mid-1950s, Moe was mostly unemployed. For the next twenty years, Berg had no real job, living off of friends and relatives who would put up with him, primarily because of his own personal charisma. When they would ask him what he did for a living, he would simply reply by putting his finger to his lips, providing them the impression that he was still a spy.

Morris “Moe” Berg died on May 29, 1972, at the age of 70, from injuries sustained in a fall at home. A nurse at the Belleville, New Jersey hospital where he died, recalled his final words as, “How did the Mets do today?” His remains were cremated and spread over Mount Scopus, in Israel.

Berg was inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame, in 1996, and into the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals, in 2000. And finally, after his death, his wartime Presidential award was posthumously acknowledged. His sister was able to accept his Medal of Freedom, in his memory. It now hangs in the Baseball Hall of Fame, in Cooperstown, New York.

Berg was inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame, in 1996, and into the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals, in 2000. And finally, after his death, his wartime Presidential award was posthumously acknowledged. His sister was able to accept his Medal of Freedom, in his memory. It now hangs in the Baseball Hall of Fame, in Cooperstown, New York.

Moe Berg’s selfless service to his country is also honored in one other way. His official baseball card is the only such card, on public display, at the CIA Headquarters, in Washington, DC.

To learn more about the fascinating life of Moe Berg, look for the movie “The Catcher Was A Spy,” starring Connie Nielsen, Paul Rudd, and Mark Strong. It was released on January 18, 2018.

1. In 1934, Moe Berg was considered…

a) as good as Babe Ruth

b) the best catcher ever

c) just a mediocre ballplayer

2. Moe had a reputation for being:

a) extremely strong

b) extremely intelligent

c) extremely courageous

3. Because of this he was able to:

a) always hit home runs when he was at bat

b) fight any referee whose call he disagreed with

c) speak 15 languages

4. Moe traveled with the U.S. baseball team to Japan in 1934 because:

a) he was a great catcher

b) he was a highly trained United States spy

c) he could recruit more good players because he spoke Japanese.

5. The reason Moe went to hear a lecture by the German physicist Heisenberg is:

a) they were friends in America

b) he needed to find out if the Nazis were building the first atomic bomb

c) he wanted to become a physicist

6. When World War II was over, Moe received:

a) the Presidential Medal of Freedom

b) a Purple Heart

c) a plaque from the president

7. The CIA headquarters in Washington DC. has:

a) the first baseball that Moe caught

b) the baseball bat he used with his name on it

c) his official baseball card