THOUGHTS FROM A DISABILITY RIGHTS ACTIVIST ON THE CIVIL RIGHTS MODEL VERSUS SEARCHING FOR CURES:

THOUGHTS FROM A DISABILITY RIGHTS ACTIVIST ON THE CIVIL RIGHTS MODEL VERSUS SEARCHING FOR CURES:

A PROPOSED NEW DIALECTICAL MINDSET

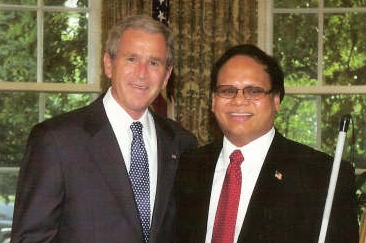

by Ollie Cantos (from https://www.facebook.com/ollie.cantos/)

by Ollie Cantos (from https://www.facebook.com/ollie.cantos/)

Editor’s Note: Ollie Cantos, is currently a Special Assistant to the Assistant Secretary of the Office for Civil Rights within the United States Department of Education. He previously served as an Attorney Advisor for the Disability Rights Section of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. Mr. Cantos is the the highest-ranking blind person in the federal government.

Editor’s Note: Ollie Cantos, is currently a Special Assistant to the Assistant Secretary of the Office for Civil Rights within the United States Department of Education. He previously served as an Attorney Advisor for the Disability Rights Section of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. Mr. Cantos is the the highest-ranking blind person in the federal government.

Since persons with disabilities first started speaking up in the spirit of self-determination to assert that we each can and must speak for ourselves regarding the ultimate course of our lives, there has emerged a philosophical divide between the medical establishment and their allies on one side and a growing number of individuals with all types of disabilities who have been coalescing into an organized community of support on the other. The traditional approach was to view disability within what is known as “the medical model” in which our conditions are pathologized in order to ascertain the causes and effects of disease. However, most notably over the past several decades with the rise of social movements, those from among an increasingly vocal and organized segment of people with disabilities have brought their voices together rightfully to assert that we are fine, just the way we are.

Since persons with disabilities first started speaking up in the spirit of self-determination to assert that we each can and must speak for ourselves regarding the ultimate course of our lives, there has emerged a philosophical divide between the medical establishment and their allies on one side and a growing number of individuals with all types of disabilities who have been coalescing into an organized community of support on the other. The traditional approach was to view disability within what is known as “the medical model” in which our conditions are pathologized in order to ascertain the causes and effects of disease. However, most notably over the past several decades with the rise of social movements, those from among an increasingly vocal and organized segment of people with disabilities have brought their voices together rightfully to assert that we are fine, just the way we are.  In fact, from time to time, during various informal conversations over the years, through a number of iterations around essentially the same question, people would ask me, “If you had the choice between a million dollars and being able to see 20/20, which choice would you pick?” I would pause for a moment, just for effect, and my answer would always be the same. “I’ll take the cash please, especially if it’s tax free,” I’ would quip and exclaim with a smile and a laugh. Particularly as I look back on the life I have lived so far, as tough as times have been for reasons having absolutely nothing to do with my inherent ability and worth but more having to do with my own original attitudes along with those of others, I love the life I have gotten to live, and I remain truly grateful for it all, including thanking God for unanswered prayers.

In fact, from time to time, during various informal conversations over the years, through a number of iterations around essentially the same question, people would ask me, “If you had the choice between a million dollars and being able to see 20/20, which choice would you pick?” I would pause for a moment, just for effect, and my answer would always be the same. “I’ll take the cash please, especially if it’s tax free,” I’ would quip and exclaim with a smile and a laugh. Particularly as I look back on the life I have lived so far, as tough as times have been for reasons having absolutely nothing to do with my inherent ability and worth but more having to do with my own original attitudes along with those of others, I love the life I have gotten to live, and I remain truly grateful for it all, including thanking God for unanswered prayers.

My response to the million-dollar question is sometimes met with surprise, and individuals would often say something like, “Wow, Ollie. I just can’t imagine what it would be like to be blind. I would have to admit that I’d make a different choice. No offense.”

My response to the million-dollar question is sometimes met with surprise, and individuals would often say something like, “Wow, Ollie. I just can’t imagine what it would be like to be blind. I would have to admit that I’d make a different choice. No offense.”

No offense taken, particularly when people are willing to expand their horizons by pondering on new paradigms. Each of us, no matter who we are, incorporates into our lives a number of beliefs and assumptions. These are formed by a myriad of life experiences, influence from others, and our own way of thinking. Each of these elements has an impact on the others. We are each afraid of the unfamiliar, the unknown. And, most particularly when being unfamiliar of the direct experiences of those having medical conditions that we are ourselves do not have, it is almost beyond our comprehension to imagine what life would be like to have that specific medical condition.

No offense taken, particularly when people are willing to expand their horizons by pondering on new paradigms. Each of us, no matter who we are, incorporates into our lives a number of beliefs and assumptions. These are formed by a myriad of life experiences, influence from others, and our own way of thinking. Each of these elements has an impact on the others. We are each afraid of the unfamiliar, the unknown. And, most particularly when being unfamiliar of the direct experiences of those having medical conditions that we are ourselves do not have, it is almost beyond our comprehension to imagine what life would be like to have that specific medical condition.

In a comprehensive training called “WINDMILLS,” which I took a number of years ago, there was an old exercise that was once facilitated among persons with and without different types of disabilities. In that exercise, we were told that we would be acquiring a particular disability but that we could choose. We had the choice between blindness, deafness, being a wheelchair user, having a psychiatric disability, possessing a learning disability, and having an intellectual or developmental disability. The catch was that, if any particular person really did have a specific disability within any of these categories, they were not authorized to pick their own. We were then asked personally to decide which disability we would most be comfortable with having and which one we would be least comfortable with having.

In a comprehensive training called “WINDMILLS,” which I took a number of years ago, there was an old exercise that was once facilitated among persons with and without different types of disabilities. In that exercise, we were told that we would be acquiring a particular disability but that we could choose. We had the choice between blindness, deafness, being a wheelchair user, having a psychiatric disability, possessing a learning disability, and having an intellectual or developmental disability. The catch was that, if any particular person really did have a specific disability within any of these categories, they were not authorized to pick their own. We were then asked personally to decide which disability we would most be comfortable with having and which one we would be least comfortable with having.

Subsequently, open and honest discussions would occur regarding why we selected as we did. Ahead of time, everyone agreed not to have judgments. What then resulted was an incredible and enlightening discussion in which we identified our own deeply-held perceptions, which were then thoughtfully addressed by people who had those disabilities. Plus, as part of the discussion, the facilitator shared examples of both contemporary and historic role models, possessing disabilities within each named category. We each came away with a deeper understanding about the disabilities possessed by others, recognizing that we must each continually evaluate and even challenge the limits of what we believe to be possible. We also learned very fundamentally about how we must assess on a regular basis the quality of life that we associate people with specific types of disabilities actually having. All the while, we may increase awareness of the true experiences of others while being open to describing our own.

Subsequently, open and honest discussions would occur regarding why we selected as we did. Ahead of time, everyone agreed not to have judgments. What then resulted was an incredible and enlightening discussion in which we identified our own deeply-held perceptions, which were then thoughtfully addressed by people who had those disabilities. Plus, as part of the discussion, the facilitator shared examples of both contemporary and historic role models, possessing disabilities within each named category. We each came away with a deeper understanding about the disabilities possessed by others, recognizing that we must each continually evaluate and even challenge the limits of what we believe to be possible. We also learned very fundamentally about how we must assess on a regular basis the quality of life that we associate people with specific types of disabilities actually having. All the while, we may increase awareness of the true experiences of others while being open to describing our own.

But, back to the issue of the medical model versus the civil rights model. The prevailing premise would almost be that the former somehow reduces the lives of people with disabilities needing to be “fixed” due to reasons of medical defect, while the latter school of thought places emphasis on advocating for removal of physical, programatic, and attitudinal barriers to full participation in every aspect of societal life.

But, back to the issue of the medical model versus the civil rights model. The prevailing premise would almost be that the former somehow reduces the lives of people with disabilities needing to be “fixed” due to reasons of medical defect, while the latter school of thought places emphasis on advocating for removal of physical, programatic, and attitudinal barriers to full participation in every aspect of societal life.

I respectfully propose a modification to how we tackle the question of cure versus civil rights. Instead of viewing these as polar opposites that are in conflict (i.e., an “us versus them” mentality), what if we employed a new dialectic approach that combines the strengths of pursuit of health with the strengths of embracing civil rights? In other words, as an alternative to health quality VERSUS civil rights, why not focus on health quality *AND* civil rights?”

I respectfully propose a modification to how we tackle the question of cure versus civil rights. Instead of viewing these as polar opposites that are in conflict (i.e., an “us versus them” mentality), what if we employed a new dialectic approach that combines the strengths of pursuit of health with the strengths of embracing civil rights? In other words, as an alternative to health quality VERSUS civil rights, why not focus on health quality *AND* civil rights?”

Let me explain, using my own disability as an illustration. (And, get ready, folks, for a little thought-provoking discussion.) Within the blindness world, entire government entities are dedicated toward addressing causes and identifying treatments and cures for blindness and visual impairment. In addition to university studies across the country, the National Eye Institute under the National Institutes of Health within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services strive to develop cutting-edge medical interventions. In the medical space, the Foundation Fighting Blindness raises millions of dollars to bolster leading research. Those wishing to avail themselves of such efforts should feel free to do so in order to preserve sight if they so choose. Concurrently, those individuals may join forces with organizations whose leaders are elected by our own community members, embracing the civil rights model which asserts that we have a right to live in the world, rich with the brightness of promise and possibility. (Some may choose to be a part of the National Federation of the Blind as I have done, and other friends are with the American Council of the Blind. Still additional friends are involved with neither but are nevertheless active within the blindness world such as those with the American Foundation for the Blind, National Industries for the Blind, Blinded Veterans Association, etc.) In so doing, we optimize the best of both worlds in accordance with the dictates of our own respective belief systems.

Let me explain, using my own disability as an illustration. (And, get ready, folks, for a little thought-provoking discussion.) Within the blindness world, entire government entities are dedicated toward addressing causes and identifying treatments and cures for blindness and visual impairment. In addition to university studies across the country, the National Eye Institute under the National Institutes of Health within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services strive to develop cutting-edge medical interventions. In the medical space, the Foundation Fighting Blindness raises millions of dollars to bolster leading research. Those wishing to avail themselves of such efforts should feel free to do so in order to preserve sight if they so choose. Concurrently, those individuals may join forces with organizations whose leaders are elected by our own community members, embracing the civil rights model which asserts that we have a right to live in the world, rich with the brightness of promise and possibility. (Some may choose to be a part of the National Federation of the Blind as I have done, and other friends are with the American Council of the Blind. Still additional friends are involved with neither but are nevertheless active within the blindness world such as those with the American Foundation for the Blind, National Industries for the Blind, Blinded Veterans Association, etc.) In so doing, we optimize the best of both worlds in accordance with the dictates of our own respective belief systems.

Medical model traditionalists need not justify their efforts by ascribing tragedy to blindness or visual impairment. Lest they do, we who are blind will surely have much to say in rigorous opposition. By the same token, those of us who focus our primary attention on civil rights need not denigrate the work of medical professionals and alternative interventions simply when they endeavor through their strengths to minimize impacts that a segment of the disability community wishes to see minimized while .contemporaneously recognizing in a sizable number of situations that disability may feasibly be reduced to a mere nuisance and characteristic when provided with quality training and an opportunity to succeed.

Medical model traditionalists need not justify their efforts by ascribing tragedy to blindness or visual impairment. Lest they do, we who are blind will surely have much to say in rigorous opposition. By the same token, those of us who focus our primary attention on civil rights need not denigrate the work of medical professionals and alternative interventions simply when they endeavor through their strengths to minimize impacts that a segment of the disability community wishes to see minimized while .contemporaneously recognizing in a sizable number of situations that disability may feasibly be reduced to a mere nuisance and characteristic when provided with quality training and an opportunity to succeed.

In a cross-disability context, I, for one, will continue actively to promote pursuit of and support for optimal health while vigorously championing disability rights advancement in every facet of community living as we each strive to reach our greatest potential. To me, especially considering the things to which I have born witness directly via the multiple initiatives to which I have given my time, both go together, hand in hand.

In a cross-disability context, I, for one, will continue actively to promote pursuit of and support for optimal health while vigorously championing disability rights advancement in every facet of community living as we each strive to reach our greatest potential. To me, especially considering the things to which I have born witness directly via the multiple initiatives to which I have given my time, both go together, hand in hand.

Provided that those dedicated to medical and natural approaches to particular conditions acknowledge that disability itself need not hold us back and provided that those in the civil rights arena acknowledge that the pursuit of cures does not necessarily mean that the condition represents some sort of defect, perhaps we may at long last put behind us the question of cures versus rights in favor of a “both and” methodology that unites the benefits of each. This way, we may set into motion the assembly of the greatest minds, all dedicated in their own ways to improving the human condition in their respective spheres.

Provided that those dedicated to medical and natural approaches to particular conditions acknowledge that disability itself need not hold us back and provided that those in the civil rights arena acknowledge that the pursuit of cures does not necessarily mean that the condition represents some sort of defect, perhaps we may at long last put behind us the question of cures versus rights in favor of a “both and” methodology that unites the benefits of each. This way, we may set into motion the assembly of the greatest minds, all dedicated in their own ways to improving the human condition in their respective spheres.

them.

them.  (where applicable) for word references and translations.

(where applicable) for word references and translations. (where applicable) to hear passages read.

(where applicable) to hear passages read. (where applicable) to see learning cues while hearing passages read.

(where applicable) to see learning cues while hearing passages read.