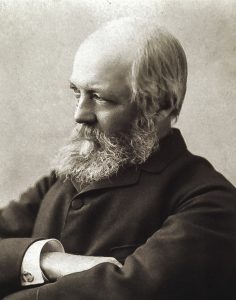

Frederick Law Olmsted

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, cities in America underwent tremendous changes. More people were moving to the cities than ever before. It became evident that cities needed to be transformed into more hospitable places, and not just centers of commerce.

No longer could the leaders of society, or the City Fathers, sit back and watch the Cities operate without more oversight. Toward the end of the 1850s, city beautification became an issue that more and more leaders followed and explored. The theory behind this movement was that the more aesthetically pleasing you make a city, the more people will want to live in that city, and the happier they will be.

No longer could the leaders of society, or the City Fathers, sit back and watch the Cities operate without more oversight. Toward the end of the 1850s, city beautification became an issue that more and more leaders followed and explored. The theory behind this movement was that the more aesthetically pleasing you make a city, the more people will want to live in that city, and the happier they will be.

One of the greatest champions of the “City Beautiful” movement was Frederick Law Olmsted. Olmsted was the leading landscape architect of the post-Civil War generation, and he has long been acknowledged as the founder of American landscape architecture.

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) was born in Hartford, Connecticut. He was raised as a gentleman, and while he never fully attended college, he did become a very learned man. When he was 18, Olmsted moved to New York to begin a career as a scientific farmer. Soon after that career failed to take off, he toured Europe with his brother, served as a merchant seaman, and traveled throughout the southern United States as a newspaper correspondent, publishing several books as an outgrowth of that career.

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) was born in Hartford, Connecticut. He was raised as a gentleman, and while he never fully attended college, he did become a very learned man. When he was 18, Olmsted moved to New York to begin a career as a scientific farmer. Soon after that career failed to take off, he toured Europe with his brother, served as a merchant seaman, and traveled throughout the southern United States as a newspaper correspondent, publishing several books as an outgrowth of that career.

Through several connections gained as a columnist with the New Yorker, in 1857, Olmsted was able to gain an appointment as the Superintendent of Central Park, New York City. This was early in the development of that park’s project planning. He soon met Calvert Vaux, who had been working on a design for the park with Andrew Jackson Downing. When Downing died, Vaux approached Olmsted about collaborating on the project. Their plan, titled “Greensward,” was ultimately selected as the winning design.

In 1859, Olmsted married the widow of his brother, John, and he adopted her children. In 1861, Olmsted obtained a leave of absence from his duties at Central Park, so that he could serve as the Executive Secretary (the head of administration) of the United States Sanitary Commission, an early version of the Red Cross, which was responsible for aiding the well-being of the soldiers of the Union Army during the Civil War.

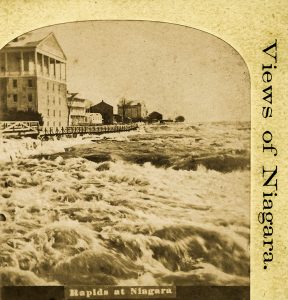

In 1863, he was offered the position as manager at the Mariposa Estate in California, a gold mining venture north of San Francisco. He left the Sanitary Commission and headed west. He later returned to New York, when the California project failed, joining Vaux in designing Prospect Park (1865-1873), Chicago’s Riverside subdivision, Buffalo’s park system (1868-1876), and the Niagara Reservation at Niagara Falls (1887).

In 1863, he was offered the position as manager at the Mariposa Estate in California, a gold mining venture north of San Francisco. He left the Sanitary Commission and headed west. He later returned to New York, when the California project failed, joining Vaux in designing Prospect Park (1865-1873), Chicago’s Riverside subdivision, Buffalo’s park system (1868-1876), and the Niagara Reservation at Niagara Falls (1887).

In 1883, he departed from New York City, and he relocated his practice to Brookline, Massachusetts. Olmsted had begun work on a park system for the City of Boston, and eventually, he focused much of his time on the Emerald Necklace. This, along with his work on the design of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, was among the last of Olmsted’s projects. In 1895, due to failing health, Olmsted turned the firm over to his partners, and soon senility forced him to be confined in the McLean Hospital at Waverly, Massachusetts. Ironically, Olmsted had designed the grounds of that very institution.

In 1883, he departed from New York City, and he relocated his practice to Brookline, Massachusetts. Olmsted had begun work on a park system for the City of Boston, and eventually, he focused much of his time on the Emerald Necklace. This, along with his work on the design of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, was among the last of Olmsted’s projects. In 1895, due to failing health, Olmsted turned the firm over to his partners, and soon senility forced him to be confined in the McLean Hospital at Waverly, Massachusetts. Ironically, Olmsted had designed the grounds of that very institution.

Frederick Law Olmsted died on August 28, 1903. The landscape architecture firm that he had founded was continued by his sons and their successors, until 1980. Subsequently, his home and office were purchased by the National Park Service, and they were opened to the public as a museum. His papers are now housed in the Library of Congress, while the Olmsted National Historic site preserves the drawings and plans for much of Olmsted and his firm’s body of work.

Olmsted designed the breathtaking gardens at the Vanderbilts’ Biltmore Estate, in Asheville, N.C.: