From Oracy to Literacy and Back Again:

From Oracy to Literacy and Back Again:

Investing in the Education of Adults, To Improve the Educability of Children!

by Thomas Sticht

Contents

|

If we focus our limited resources on reaching first-time parents, then one “dose” of parenting, could also benefit succeeding children. [Sticht, 2011] |

|

|

|

|

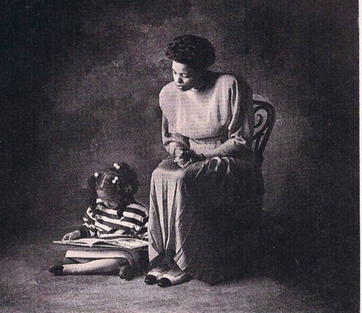

Mothers enrolled in basic-skills programs reported that they spoke with their children about school more, read to them more, and took them to the library more. [Sticht, 2011]

|

12-28-18 update: Stopping Adult Illiteracy at the Source

Oracy, Adult Literacy Research, and The Fourth-Grade Plunge

|

|

Definition of oracy: Speaking with and auding oral language. Tom Sticht speaks while Princess Anne of the United Kingdom auds. |

Introductory note: The term “oracy” referring to listening and speaking was coined by Andrew Wilkinson of the United Kingdom in the 1960s. The word “auding” as a parallel term to reading was coined by a blind student, D. P. Brown, in 1954 while working on his Ph.D at Stanford University. He drew the parallel as: hearing, listening, auding in relation to seeing, looking, reading. Both auding and reading involve the use of language in addition to the specific modality factors. All auding includes listening and hearing while languaging. All reading includes looking and seeing while languaging. Languaging refers to the processes involved in producing language representations of knowledge.

In September 2002, The Partnership for Reading published a report authored by John Kruidenier entitled Research-Based Principles for Adult Basic Education Reading Instruction. The report laments the paucity of research on adult reading and discusses how it draws upon K-12 research to inform adult reading instruction when that is appropriate. Missing in most of the recent guidance on scientific, evidence-based research for teaching children to read is any reference to adult literacy research that can inform K-12 educational practice.

However, the Spring 2003 issue of the American Educator, a journal of the American Federation of Teachers, an AFL-CIO labor organization for educators, published a special issue with the title “The Fourth-Grade Plunge: The Cause, the Cure.” The cover of the special includes a summary that states: “In fourth grade, poor children’s reading comprehension starts a drastic decline, and rarely recovers. The Cause: They hear millions fewer words at home than do their advantaged peers, and since words represent knowledge, they don’t gain the knowledge that underpins reading comprehension. The Cure: Immerse these children, and the many others whose comprehension is low, in words, and the knowledge that the words represent, as early as possible.

Inside the journal, the major article is by E. D. Hirsch, Jr., author of the best-selling and controversial book, Cultural Literacy. In the present article, Hirsch offers one approach to building children’s comprehension ability in a section called, Build Oral Comprehension and Background Knowledge. The section begins with the statement, “Thomas Sticht has shown that oral comprehension typically places an upper limit on reading comprehension; if you don’t recognize and understand the word when you hear it, you also won’t be able to comprehend it when reading. This tells us something very important: oral comprehension generally needs to be developed in our youngest readers if we want them to be good readers.” Hirsch cites Sticht, et al (1974), in support of his statement. In an earlier book, Hirsch (1996) has referred to the limits of oral language comprehension on reading comprehension, once decoding has been acquired, as “Sticht’s Law.”

Later in this special issue of the American Educator, Andrew Biemiller, a professor at the Institute of Child Study at the University of Toronto, extends Hirsch’s point in an article entitled, Oral Comprehension Sets the Ceiling on Reading Comprehension. In support of his argument, Biemiller cites a chapter by Sticht & James (1984) which includes an extended discussion of the concepts of “oracy to literacy transfer,” and the use of listening assessment to determine “reading potential.”

What I have found particularly interesting is that these articles cite research by colleagues, and myself, that was done as part of a program of research to better understand adult reading education, not childhood reading. Almost 30 years ago, to aid in the better understanding of adult literacy issues, colleagues and I wrote Auding and Reading: A Developmental Model to provide a summary and synthesis of how the “typical child,” a theoretical abstraction of course, born into our literate society, grows up to become literate in the judgment of other adults. This was done to provide a frame of reference for better understanding of how it is that some children, unlike the “typical child,” grow up to be less than adequately literate in the judgment of other adults, and who might benefit from participating in an adult literacy program.

The Auding and Reading book offered guidance for adult reading instruction that presaged the present guidance in the American Educator for K-12 education. For instance, on page 122 of Auding and Reading, we stated the need for: “Methods for improving oral language skills as foundation skills for reading. In this regard, it would seem that, at least with beginning or unskilled readers, a sequence of instruction in which vocabulary and concepts are first introduced and learned via oracy skills would reduce the learning burden by not requiring the learning of both vocabulary and decoding skills at the same time. It is difficult to see how a person can learn to recognize printed words by “sounding them out” through some decoding scheme if, in fact, the words are not in the oral language of the learner. Thus an oracy-to-literacy sequence of training would seem desirable in teaching vocabulary and concepts to unskilled readers.”

The Auding and Reading book goes on to discuss concepts of automaticity in decoding, which underlies fluency of decoding in both auding and reading, and why it is important to develop fluency (automaticity) of decoding for the constructive processes involved in comprehension by languaging to proceed, either by auding (listening to and comprehending the spoken language), or by reading the written language.

It is indicative of the rather long time that it takes for ideas to be disseminated and assimilated in a field of knowledge that, this year, the American Educator, which reaches a million or so educators, has brought many of the ideas from adult literacy research into the arena of K-12 education.

There remains a need for further understanding of the life span changes that affect reading. For instance, the National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS) of 1993 indicated that as adults got older, their performance of NALS literacy tasks dropped. In research on the use of the telephone to assess literacy, colleagues and I found that we could draw upon the theoretical foundation of literacy given in the Auding and Reading book, and subsequent research on listening and reading to assess knowledge development across the life span. In this case, we found that older adults knew more than younger adults about a wide range of subjects.

|

Tom Sticht studies adults learning by auding and reading.  |

We used techniques that did not overload working memory, like most of the NALS tasks do. Because older adults generally lose some working memory capacity, we felt that NALS type tasks are inappropriate for assessing the literacy ability of older adults. Whatever the case, the fact that adults change across the life span argues for more research to better understand literacy development in adulthood beyond what we have learned today, and what we can gleam from studying the literacy development of children.

Interestingly, as the American Educator for Spring 2003 illustrates, what new learning we acquire about adult literacy development across the life span may have additional, important implications for K-12 literacy education. This adds weight to the importance of policies that emphasize the need for research on adult literacy education.

The “Reading Potential” Concept: From Vienna’s Rathaus to the Common Core State Standards

Vienna’s magnificent Rathaus, or Town Hall, hosted an evening dinner and ball for the International Reading Association’s 5th World Congress on Reading in August of 1974. My wife, Jan, and I were seated with George and Evelyn Spache. At the time, I was conducting research using the Diagnostic Reading Scales (DRS) that George had developed in the 1960s, and revised in 1972. We discussed the “reading potential” concept that the DRS were designed to measure, by revealing the grade level at which a person could comprehend a story by listening, in comparison to the level at which they could comprehend stories by reading. If listeners could listen to and comprehend up to an 8th grade passage, but could only comprehend up to passages at the 5th grade level by reading, then they were said to have a 5th grade reading level, but an 8th grade “reading potential.”

Vienna’s magnificent Rathaus, or Town Hall, hosted an evening dinner and ball for the International Reading Association’s 5th World Congress on Reading in August of 1974. My wife, Jan, and I were seated with George and Evelyn Spache. At the time, I was conducting research using the Diagnostic Reading Scales (DRS) that George had developed in the 1960s, and revised in 1972. We discussed the “reading potential” concept that the DRS were designed to measure, by revealing the grade level at which a person could comprehend a story by listening, in comparison to the level at which they could comprehend stories by reading. If listeners could listen to and comprehend up to an 8th grade passage, but could only comprehend up to passages at the 5th grade level by reading, then they were said to have a 5th grade reading level, but an 8th grade “reading potential.”

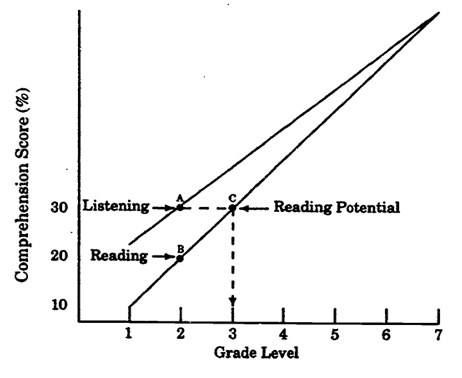

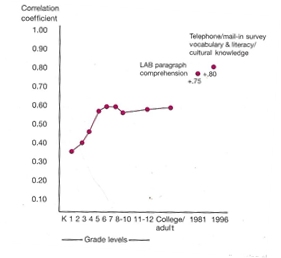

Also in 1974, colleagues and I published an extensive review of listening and reading research in which we found that empirical studies confirmed the idea of “reading potential,” and indicated that, on average, listening comprehension (auding) ability surpassed reading ability with children from kindergarten up to about the 7th or 8th grades, when listening and reading converged, and became equal means of comprehending spoken or written language (Sticht, et al, 1974).

Our review also showed that children with greater listening comprehension ability before beginning school tended to become the better readers after entering school and learning print decoding, and those with less listening comprehension ability tended to become the weaker readers after learning to decode the written language.

A decade later, in 1984, I participated in a national conference in support of President Reagan’s Adult Literacy Initiative, which he had announced on September 7, 1983. At lunch, I sat at a table with E. D. “Don” Hirsch, Jr., who was also a speaker at the conference. His presentation included a summary of research showing that both children’s and adults’ prior knowledge about a topic helped them to read and comprehend that topic. He stated: “Adult literacy is less a system of skills than a system of information. What chiefly counts in higher reading competence is the amount of relevant prior knowledge that readers have” (Hirsch, 1984).

In 1996, Hirsch wrote that conceptual and vocabulary knowledge gained by children, through speaking and listening to oral language, greatly affected their ability to comprehend by reading. He said: “I have not yet mentioned reading and writing. That is because speaking and listening competencies are primary. There is a linguistic law that deserves to be called “Sticht’s Law,” having been disclosed by some excellent research by Thomas Sticht. He found that reading ability in non-deaf children cannot exceed their listening ability. Sticht showed that, for most children, by seventh grade, the ability to read with speed and comprehension, and the ability to listen, had become identical” (Hirsch, 1996, pp. 146-147). In support of these comments, Hirsch cited works by colleagues and myself (Sticht & James, 1984; Sticht, et al., 1974), both of which addressed the “reading potential” concept as discussed above, and the predictive relationships between listening and reading comprehension at different ages and grades of schooling.

The “Reading Potential” Concept in the Common Core State Standards (CCSS)

In Appendix A for the CCSS for English language arts and literacy, the “Reading Potential” and predictive relationships among listening and reading comprehension concepts are implicitly stated in the discussion of the relationships of oral language to written language: “Oral language development precedes, and is the foundation for, written language development; in other words, oral language is primary, and written language builds on it. Children’s oral language competence is strongly predictive of their facility in learning to read and write: listening and speaking vocabulary, and even mastery of syntax, set boundaries as to what children can read and understand, no matter how well they can decode … early language advantage persists and manifests itself in higher levels of literacy. A meta-analysis by Sticht and James (1984) indicates that the importance of oral language extends well beyond the earliest grades. Sticht and James found evidence strongly suggesting that children’s listening comprehension outpaces reading comprehension until the middle school years (grades 6–8).”

The Oracy to Literacy Transfer Effect in Improving Reading Comprehension

In the CCSS, to increase children’s “reading potential,” teachers are advised to raise children’s conceptual knowledge and vocabulary through talking and listening, i.e. the “oracy skills,” as a means of increasing the children’s “literacy skills” following the acquisition of decoding skills. To promote this “oracy to literacy” transfer, Appendix A of the CCSS states: “Because, as indicated above, children’s listening comprehension likely outpaces reading comprehension until the middle school years, it is particularly important that students in the earliest grades build knowledge through being read to, as well as through reading, with the balance gradually shifting to reading independently.”

From the Vienna Rathous in 1974 to the CCSS in 2015, the idea that listening comprehension precedes reading comprehension, and establishes an initial “reading potential” for the latter, is a well-established understanding in children’s early education. Additional research indicates that the “reading potential” concept may also be usefully applied in the assessment and instruction of adult literacy learners (Sticht, 1979).

Oracy: The Bridge to Literacy From Parents to Their Progeny

The use of oracy to promote interest in and the achievement of literacy has a long history. Writing in 1908, Edmund Burke Huey made the point that “meaning inheres in this spoken language and belongs but secondarily to the printed symbols.” He also commented on the importance of parents reading to their children, saying “The secret of it all lies in the parent’s reading aloud to, and with, the child.”

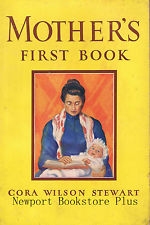

The latter was an idea which Cora Wilson Stewart, the founder in 1911 of the famous Moonlight Schools of Kentucky for illiterate adults, drew upon in writing her 1930 Mother’s First Book: A First Reader for Home Women. She knew the importance of children having literate parents, and especially literate mothers who could read to them. In her book for mothers, she was direct in her guidance regarding the use of oracy, stating to tutors that, “The first reading lesson should be made interesting by conversation, in which the pupil is led by the teacher’s questions and suggestions to speak the sentence before she sees it in print. Then when it is presented, the teacher may say, “Here are the words in print that you have just spoken—see my baby. The sentence then comes to the pupil with new interest.” Later, this technique of teaching literacy by first using oracy, came to be known as the “language experience” approach.

The latter was an idea which Cora Wilson Stewart, the founder in 1911 of the famous Moonlight Schools of Kentucky for illiterate adults, drew upon in writing her 1930 Mother’s First Book: A First Reader for Home Women. She knew the importance of children having literate parents, and especially literate mothers who could read to them. In her book for mothers, she was direct in her guidance regarding the use of oracy, stating to tutors that, “The first reading lesson should be made interesting by conversation, in which the pupil is led by the teacher’s questions and suggestions to speak the sentence before she sees it in print. Then when it is presented, the teacher may say, “Here are the words in print that you have just spoken—see my baby. The sentence then comes to the pupil with new interest.” Later, this technique of teaching literacy by first using oracy, came to be known as the “language experience” approach.

A third major figure in the field of literacy instruction, and one who like Cora Wilson Stewart focused upon the use of oracy in adult literacy instruction, was Paulo Freire, the great Brazilian educationist and philosopher. In describing what became known world-wide as the Pedagogy of the Oppressed, the title of Freire’s most famous book, Paulo Freire described his techniques of using “culture circles” to promote interest in learning literacy.

In his “culture circles”, Freire first had adult learners study pictures depicting various scenes, and discuss what in the scene was made by nature, and what was made by humans. His aim was to get the learners to come to realize through their discussion (oracy) the difference between what nature produced and what humans (culture) produced. The purpose of this was to get the adults to come to realize that the oppressive conditions under which they lived were not the result of nature, but of human culture, and that culture could be changed by their actions. Then literacy, as a cultural tool to be used in changing the conditions of their lives, was taught using emotional words taken from the oracy discussions.

Like Stewart and Freire, Huey recognized that in many cases parents might not be literate enough to help their children learn to read and write at home before they began their formal schooling. For these parents, he recommended, therefore, that the school “will have as one of its important duties the instruction of parents in the means of assisting the child’s natural learning in the home.”

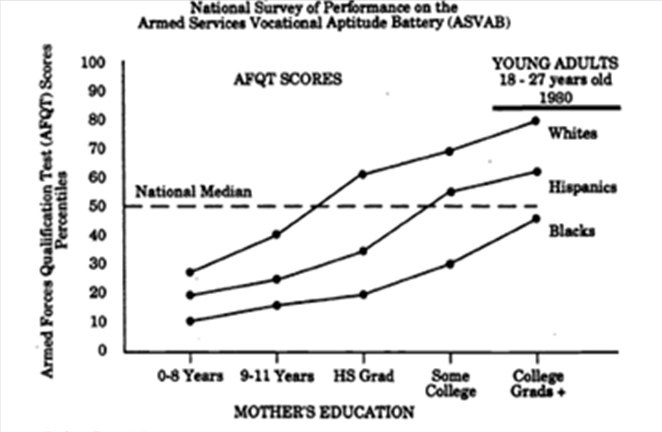

Today, tens of thousands of undereducated adults, who are or are about to become parents, are being assisted to develop their own literacy skills and those of their children in family literacy programs that work with both children and adults. These programs are more and more emphasizing the importance of the oracy skills, both for adults and their children. Data from over thirty years of national assessments of reading in the United States repeatedly show that as their parent’s years of education increases, the literacy skills of their children increase. Better educated adults have better educated children.

| Performance of Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites on the 1980 Armed Forces Qualification Test of Reading (Word Knowledge and Paragraph Comprehension) and Mathematics as a function of Mother’s Education Level. |

|

Additional research has indicated that much of this intergenerational transfer of literacy is due to the parent’s use of oracy. In general, better educated parents, especially mothers, expose their children to greater amounts of oral language in their early lives. Thus, the more likely the child is to acquire a large oral vocabulary and a large amount of conceptual knowledge, expressible and comprehensible by oracy. In turn, this provides the children with the foundation for achieving higher levels of literacy, once they enter school.

The professional wisdom of Huey, Stewart, and Freire, in emphasizing the importance of oracy in the development of literacy, has found support in a large body of scientific research. It would seem prudent, therefore, to focus a greater amount of resources on understanding how to bring about greater levels of oracy among adults. It appears, that to a large extent, oracy is the bridge to literacy from parents to their progeny.

New Report Confirms a Hundred Years of Professional Wisdom About Parent’s Role in Developing Children’s Literacy Skills

A hundred years ago, Edmund Burke Huey published his classic work, The Psychology and Pedagogy of Reading (1908) (reprinted by the MIT Press in 1968). In his book, Huey passed on professional wisdom about reading, and the teaching of reading of his day.

Now, a century later, an extensive study of early childhood literacy development has been published (U. S. Government, 2008) and its findings are remarkably reminiscent of Huey’s ideas of 1908. To illustrate this similarity, following are some extracts of paragraphs from some of Huey’s book chapters along with the results from the Developing Early Literacy (DEL) report.

|

|

Growth in correlations between listening (auding) and reading from various studies for children and adults ( Sticht, 2008). |

Huey: Chapter VI. The Inner Speech of Reading And the Mental and Physical Characteristics of Speech. “The child comes to his first reader with his habits of spoken language fairly well formed, and these habits grow more deeply set with every year. His meanings inhere in this spoken language and belong but secondarily to the printed symbols. To read is, in effect, to translate writing into speech.” (Huey, 1908/1968, pp. 122-123).

Here Huey makes the point that in learning to read the child learns to decode written language into his or her prior oral language. This means, of course, that children with higher levels of oral language will become the better readers when they learn to decode the written language back into their spoken language.

DEL study: Following a study in which the DEL looked at how well various measures of literacy (e.g., alphabet knowledge, etc. and measures of oral language, including oral vocabulary and listening comprehension) predicted reading achievement when children entered school, the authors concluded that along with other variables, “…more complex aspects of oral language, such as grammar, definitional vocabulary, and listening comprehension, had more substantial predictive relations with later conventional literacy skills” (p. 79). In these analyses, listening comprehension of preschool children tended to correlate mildly with their reading comprehension in kindergarten, first grade, or second grade.

Importantly, however, the authors seemed to overlook the relationship to be expected between listening and reading comprehension as children enter school and progress up the grades. In a discussion of factors that can influence the size of correlations, the authors say, “Another factor that can affect the size of the correlation is the length of time from the assessment of the predictor to the measurement of the dependent variable. Correlations would presumably be lower, on average, with longer intervals of time in between assessments” (p. 58).

But this type of pre-school assessment and predictor of later reading ability is not appropriate when it comes to understanding how reading maps back onto listening comprehension as children go through the K-12 system. What is expected is that in the early grades the correlation of reading with listening comprehension will be low in the early grades because there is not much variation in children’s ability to comprehend the written language. As their skill increases with additional practice in the school grades, the correlations of listening and reading should increase as those with high listening skills before school become the better readers, while those with low preschool listening skills once again gain access back to their relatively low listening skills. This has in fact been substantiated by considerable research (Sticht, 2008).

Despite the DEL studies misrepresentation of the relationships among listening and reading comprehension, the study nonetheless confirms Huey’s early statement about the relationship of oral and written language. It also bears on another bit of Huey’s professional wisdom.

Huey: Chapter XVI. Learning to Read at Home. “The secret of it all lies in the parent’s reading aloud to and with the child. The ear and not the eye is the nearest gateway to the child-soul, if not indeed to the man-soul. Oral work is certain to displace much of the present written work in the school of the future, at least in the earlier years; and at home there is scarcely a more commendable and useful practice than that of reading much of good things aloud to the children” (p. 332 & 334).

DEL: After examining research on parents and teachers reading with children, the authors of Developing Early Literacy conclude: “Despite any analytical limitations, these studies indicate that shared-reading interventions provide early childhood educators and parents with a useful method for successfully stimulating the development of young children’s oral language skills” (p. 163).

|

|

Family reading together. (After Thomas, 1941) |

“Overall, the evidence supports the positive impact of shared-reading interventions that are more intensive in frequency and interactive in style on the oral language and print knowledge skills of young children” (pp. 163-164). “It seems reasonable to proceed with the idea that shared reading would help all or most subgroups of children, given the inclusion in these studies of mixed samples of children from different socioeconomic backgrounds, different ethnicities, and different living circumstances” (p.164).

Again, a hundred years later, the wisdom of educators of the 19th and early 20th centuries is confirmed in the 21st century! And there is more confirmation of this wisdom.

Huey: Chapter XV. The Views of Representative Educators Concerning Early Reading. “Where children have good homes, reading will thus be learned independently of school. Where parents have not the time or intelligence to assist in this way the school of the future will have as one of its important duties the instruction of parents in the means of assisting the child’s natural learning in the home” (pp. 311-312).

DEL: The DEL researchers evaluated research in which “the instruction of parents in the means of assisting the child’s natural learning in the home” took place, as suggested by Huey. They reported, “Some educators consider parent education an integral component of early childhood programs; however, reports of their effectiveness have varied widely. Many of the studies reviewed in this chapter were initiated with the assumption that successful PI [parental involvement] programs help parents understand the importance of their role as first teachers and equip them with both the skills and the strategies to foster their children’s language and literacy development” (p. 173). Following their research review, the DEL authors concluded, “Overall, the results…indicate that home and parent intervention programs included in these studies had a statistically significant and positive impact both on young children’s oral language skills and general cognitive abilities” ( p. 174).

Now, over a hundred years since Huey made his observations about oral language and early childhood literacy education in the home, the Developing Early Literacy (DEL) report has provided an extensive review of hundreds of research studies that place a scientific veneer on the solid professional wisdom of literacy educators.

What is needed now is the will to provide the extensive adult education that will permit parents to develop their children’s oral language skills which provide the foundation for skilled reading comprehension.

“Things are going to slide, slide in all directions. Won’t be nothing,

Nothing you can measure anymore”. – From the song “The Future”

by Leonard Cohen, Canadian Poet, Musician, Singer

Americans love measurement. Sometimes, even when common sense reveals the obvious truth of a proposition, it will be ignored until some form of objective measurement is forthcoming to support the truth of the thought expressed. Today, there is underway in the United States a large initiative aimed at closing the gap between the reading achievement of children from poorer homes and those from affluent homes. Called the “30 million word gap”, the initiative builds on the appearance of measurements based on the common sense observation that reading ability is formed on children’s earlier developed oral language ability.

An early expression of the common sense idea that reading ability is based on the earlier acquired ability to listen to and speak the native oral language is found in 1908 in Edmund Burke Huey’s classic book, “The Psychology and Pedagogy of Reading.” In this book Huey wrote about the relationship of oral to written language and said, “The child comes to his first reader with his habits of spoken language fairly well formed, and these habits grow more deeply set with every year. His meanings inhere in this spoken language and belong but secondarily to the printed symbol.”

Jumping ahead a few decades, colleagues and I surveyed large numbers of studies that measured relationships among children’s and adult’s listening and reading skills (Sticht, et al., 1974; Sticht & James, 1984). In this research we found that in the early grades of school children comprehended better by listening to rather than by reading of materials. But as they progressed through school their listening and reading abilities improved and the gap between their listening and their reading ability closed until by around the 6th to 8th grade levels they were able to comprehend equally well what they listened to or read.

A decade later another major research project, which measured the relationships of oral language ability to written language achievement, lead directly to the present “30 million word gap” initiatives. Betty Hart and Todd Risley (1995) reported their research tracking the acquisition of oral vocabulary of 42 children in the homes of welfare, working class, and professional families for two and a half years. They estimated that from birth to 4 years of age welfare children would experience some 15 million words, working class children around 30 million words, and children of professional parents would experience some 45 million words. These differences in words listened to lead to differences in oral vocabulary of the children in these three groups and in turn these differences were carried over into the school years resulting in similar differences in reading achievement among these three groups.

In the Hart & Risley study, the difference between the number of words heard by the children of the welfare and the professional groups (45-15=30 million) formed the basis for the current “30 million word gap” initiatives. In a June 25, 2014 White House Blog, Maya Shankar, Senior Advisor for the Social and Behavioral Sciences at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy said:

“Research shows that during the first years of life, a poor child hears roughly 30 million fewer total words than her more affluent peers. This is what we call the “word gap,” and it can lead to disparities not just in vocabulary size, but also in school readiness, long-term educational and health outcomes, earnings, and family stability even decades later. That’s why today we are releasing a new video message from President

Obama focused on the importance of supporting learning in our youngest children to help bridge the word gap and improve their chances for later success in school and in life.”

Perhaps this new emphasis upon educating parents to develop their children’s oral language skills will help children achieve higher education and overcome the scourge of poverty in later life. As our British cousins might say, “Mind the 30 Million Word Gap”!

Black-White Differences in Oracy and Literacy: A Needed Conversation .

The New York Times online published an article by Trip Gabriel on November 9, 2010 entitled: “Proficiency of Black Students Is Found to Be Far Lower Than Expected.” The article refers to research by the Council of the Great City Schools that indicates that: “Only 12 percent of black fourth-grade boys are proficient in reading, compared with 38 percent of white boys, and only 12 percent of black eighth-grade boys are proficient in math, compared with 44 percent of white boys . Poverty alone does not seem to explain the differences: poor white boys do just as well as African-American boys who do not live in poverty, measured by whether they qualify for subsidized school lunches.”

| According to Dr. Ferguson, these conversations include “conversations about early childhood parenting practices. The activities that parents conduct with their 2-, 3- and 4-year-olds. How much we talk to them, the ways we talk to them, the ways we enforce discipline, the ways we encourage them to think and develop a sense of autonomy.” |  |

Ronald Ferguson, director of the Achievement Gap Initiative at Harvard, commented on these findings and said: “There’s accumulating evidence that there are racial differences in what kids experience before the first day of kindergarten. They have to do with a lot of sociological and historical forces. In order to address those, we have to be able to have conversations that people are unwilling to have.”

Listening to adults speak in early childhood may, as suggested by Ferguson, produce differences in both oracy (listening to and comprehending speech) and literacy (reading). In unpublished research for the U. S. Department of Defense, colleagues and I found that there were significant differences between black and white young adults who were applicants for military service in the oracy skills involved in listening to and recalling information from spoken messages. When listening to and recalling information from a 5th grade passage spoken at 100 words per minute, whites answered correctly 95 percent of questions while blacks answered 85 percent correctly, a ten point gap. .

Surprisingly, however, when the spoken message was presented for listening at 250 words per minute, which is about the average rate for silent reading by college-oriented, high school graduates, whites got 60 percent correct while blacks got only 30 percent correct, a 30 point gap. For some reason, accelerating the rate of speech tripled the gap between recall scores for whites and blacks when the rate of speech of the spoken message was increased from 100 to250 words per minute.

The differences among black and white children in literacy persist into adulthood. The 1992 National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS) asked adults to rate their own reading skills as they perceived them. In a report on the Literacy of Older Adults in America, from the National Center for Education Statistics in Washington, DC, November 1996, the authors reported (p. 43) black/white differences in self-ratings of their reading skills:

Whites: Very Well-77%, Well-21%, or Not Well/Not AtAll-3%.

Blacks: Very Well-67%, Well-27% and Not Well/Not AtAll-6%.

Among both blacks and whites, poor reading appears to be a perceived problem for only 3 to 6 percent of these populations, about 4.5 million adults in the age range 16-59.

Importantly however, when the average proficiencies of whites and blacks on the NALS Prose scale were compared, it was found that for whites who rated themselves as reading Very Well, their average Prose proficiency was 308, well above average, whereas for blacks rating themselves as reading Very Well, their Prose average proficiency was 259, well below average.

The NALS data include both males and females, whereas the Council of the Great City Schools and the military data refers to males. Still, the NALS data indicate an important difference in blacks and whites, and that is that even though both groups overwhelmingly perceive themselves as reading Very Well or Well, there is a large gap, greater than one standard deviation, between Whites and Blacks in their measured reading abilities. .

There are other important differences in the oracy and literacy skills of black and white children and adults that beg for better understanding, including the disturbing fact that the black-white differences in oracy and literacy appear to be transmitted intergenerationally from parents to their children. Unfortunately, as Ferguson stated, it appears that achieving such understanding requires “conversations that people are unwilling to have.”

The Plight of Those With Oracy Difficulties in America

In our focus upon teaching native English speaking children and undereducated adults the literacy skills of reading and writing, we take little notice that our teaching and our student’s learning take place largely through the oracy skills of speaking and listening. Like water for fish and air for people, so embedded is our instruction of literacy within the environment of oracy that the latter is barely, if at all, noticed. .

In a 2009 report entitled Speak Up and Listen, Terry Roberts and Laura Billings of the Paideia Center at the University of North Carolina call attention to the importance of oracy skills. They point to the relative lack of instruction of teachers about oracy skills, and the lack of emphasis upon the instruction of oracy skills with students at any educational level:

“…unfortunately, too many educators fail to see the importance of teaching basic communication skills—speaking and listening—on anything like a consistent basis. The single-minded focus on standardized testing that has infiltrated almost every corner of American public education has pushed out everything that is not tested, including those skills that are at the very heart of learning to learn and learning to think. It is all the more ironic, then, that speaking and listening are 21st Century survival skills—both for their own sake and as a medium for critical thinking. …conversation is directly connected to critical thinking in general and problem solving in particular. This is also how we learn complex subjects, including the conceptual part of any standardized curriculum. In order to think clearly about math or science, history or poetry, we need consistent practice in talking about those subjects and in hearing others talk about them.”

In 2004, speaking in less academic language, Bill Cosby, world famous (now disgraced) comedian and television star, and holder of a GED high school equivalency degree, spoke at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). His speech was about the sorry state of educational achievement among many African-Americans. He was caustic in his comments about the poor Standard English language skills of a number of African-Americans and how this holds them back. He said: :

”We’ve got to take the neighborhood back. We’ve got to go in there. Just forget telling your child to go to the Peace Corps. It’s right around the corner. It’s standing on the corner. It can’t speak English. It doesn’t want to speak English. I can’t even talk the way these people talk: “Why you ain’t where you is go ra?” I don’t know who these people are. And I blamed the kid until I heard the mother talk. Then I heard the father talk.

This is all in the house. You used to talk a certain way on the corner and you got into the house and switched to English. Everybody knows it’s important to speak English except these knuckleheads. You can’t land a plane with, “Why you ain’t…” You can’t be a doctor with that kind of crap coming out of your mouth.”

.”

A report of a 2009 survey of employees (the actual workforce, not employers) entitled American Workers and Employers Agree: New Entry-Level Workers Are Not Prepared for the 21st-Century Workplace, indicates the relative importance of oracy and literacy skills as perceived by employees. When given the choices of professionalism, communication, problem solving, working in teams, reading comprehension and math/science, employees rated the most important skill set necessary to succeed in their workplace as communication (29 percent), problem solving (27 percent),professionalism (20 percent), working in teams (11 percent), reading comprehension in English (9 percent) and math/science (5 percent).

These American workers reported that some 37 percent of new entries into work were unprepared for an entry-level job in their workplace. We can only guess about the numbers of times many employers find that they cannot hire someone because the person doesn’t seem to know how to speak to and listen to customers, employers, or others in a professional manner. Anecdotal evidence, however, like that of Bill Cosby’s, suggests that we need to pay a great deal more attention to the plight of those native English speakers with difficulties in their oracy skills.

Oracy as a Predictor of Workforce Success

Numerous reports by business, industry, vocational, government, and other organizations have indicated that adults’ oracy (auding and speaking) and literacy (reading and writing) skills are related to productivity on the job and hence to a nation’s productivity in the global economy. But there is little empirical evidence that directly examines the relationships of oracy skills to the actual performance of important tasks in various jobs. Here I discuss research on auding (listening comprehension of tape recorded passages) and reading skills in relation to the performance of actual job tasks in four jobs.

Auding, Reading, and Job Performance. In the most extensive research of its kind up to the present, colleagues and I examined the relationships of auding and reading skills of Army personnel in four jobs (Armor Crewman, Cook, Automotive Repairman, Supply Clerk) to measures of job performance and job knowledge.1 The hands-on, job performance measures included actual job tasks determined by job and task analysis. For instance, Cooks cooked scrambled eggs, made jelly roles, set-up field kitchens, and other tasks. Automobile mechanics repaired broken vehicles. Supply Clerks worked in a mock-up office and completed various requisition and accountability forms. Armor Crewman performed driving in response to hand-and-arm signals, preparing a tank for battle and so forth.

The job knowledge measures were multiple choice knowledge questions derived from on-the-job interviews with personnel in which they were asked what job incumbents genuinely had to know to be able to perform their jobs effectively. This information was then used to construct job knowledge, paper-and-pencil tests.

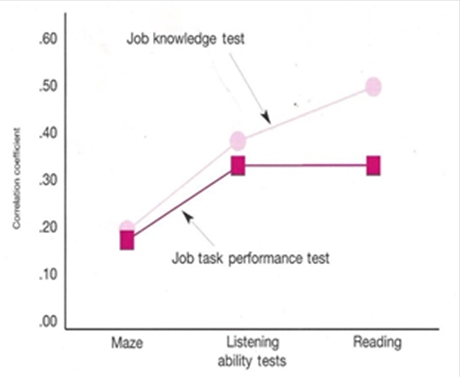

| Correlations of Maze, Listening (Auding) & Reading Tests with Job Performance and Job Knowledge Tests. After: Sticht, 2008 |

|

In each of the jobs some 400 personnel were examined using a test in which examinees traced a line through a paper-and-pencil maze as a measure of non-verbal reasoning, a listening test, and a reading test and these tests were correlated with performance on the job performance and knowledge tests.

For the hands-on, job task performance measures, out of a possible perfect relationship of 1.0, the correlations with the maze, auding, and reading tests were +.18, +.34, and +.33 respectively. Thus, auding was as highly correlated with hands-on job performance as was reading. But for the paper-and-pencil, job knowledge tests, the correlations for the maze, auding, and reading measures were +. 20, +.42, and +.49 respectively. These data suggest that because the knowledge tests directly involved the use of reading, as did the reading test, the correlation of the reading test with the knowledge test was greater than for listening and the knowledge test. Generally this represents the fact that when two tests include more similar features they tend to correlate more highly.

In separate research, colleagues and I analyzed data from some 4500 young men who applied for military service and were administered tests of auding (comprehension of spoken paragraphs by listening) and reading (comprehension of written paragraphs) along with the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT).3 The analyses compared auding and reading tests with the AFQT as predictors of attrition and promotions within military jobs. The data showed that oracy using the auding test of listening comprehension was the best predictor of attrition within the first 30 months of service. Years of education was the best predictor of promotions, reflecting in part the practice of the military services in using education as a factor in determining job advancement. The AFQT was the best test-based predictor of job promotion (pay grade achieved) and the auding test added significantly to the AFQT as a predictor of promotion.

Though the research reported here is over 20 years old, and I have not found more recent research of this kind, it reinforces the typical assertion that both oral communication skills, represented in this case by auding, and literacy (the AFQT is comprised of four paper-and-pencil tests completed by reading) are indicators of workforce readiness and are important for both job productivity and the nation’s global competitiveness. For this reason, educators at all levels of schooling, including adult basic education, need to focus more attention on improving the oracy skills of native English speakers along with those needing English as an additional language. Improved oracy as well as literacy skills can enhance the employability of adults and their advancement in work.

Some Misunderstandings About Reading

The federal government encourages the use of “scientific, evidence-based” methods of teaching the “essential components” of reading. For instance, the now non-existent National Institute for Literacy web page once stated: Scientific research has identified five components of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension.

However, this seems to me to contain certain misunderstandings about reading which I have summarized below, along with some other misunderstandings that I have seen in the literature on reading.

Misunderstanding #1: Fluency is one of “the essential components of reading” that include alphabetics (phonemics, phonics), fluency, vocabulary, comprehension.

Correction: “fluency” is not a “component” of anything. Rather it is the quality of a performance. In reading it refers to reading that is executed without a lot of mistakes, not in a slow, halting, recursive manner but rather in a regular left to right, progressive moving, fairly rapid (around 200-250 words per minute) manner when reading materials of some familiarity.

Misunderstanding #2: Vocabulary is one of “the essential components of reading” that include alphabetics (phonemics, phonics), fluency, vocabulary, comprehension.

Correction: Vocabulary is a component of language, not listening or reading, though it can be acquired using either of these information pick-up processes.

Misunderstanding #3: Comprehension is one of “the essential components of reading” that include alphabetics (phonemics, phonics), fluency, vocabulary, comprehension.

Correction: Comprehension precedes reading and directs the reading process, not the other way around. Listening to speech is one way to comprehend language, reading graphic symbols is another. Children typically learn to comprehend by listening to speech before they learn to comprehend by reading. Comprehension is what the reader tries to achieve, but comprehension is not a component of reading, it is both a precursor to and a result of reading.

Misunderstanding #4: Listening and reading are the same language processes.

Correction: Listening and reading are both information pick-up processes which may be used to construct language, but they are not language and they are not the same. You can do one in the dark, the other in a noisy room, but neither in a dark, noisy room. Languaging can be accomplished using signing and/or tactual information pick-up processes, too.

Misunderstanding #5: “First you learn to read, then you read to learn.”

Correction: Despite the wide-spread use of this old bromide, you always read to learn. Even when learning to read, one looks at the graphic displays and tries to learn (i.e., “read”) them as symbols. First you read to learn to read graphic information as symbols then you read to learn some other new information forming new ideas expressed in graphic symbols.

Misunderstanding #6: We can teach reading skills to children and adults.

Correction: We cannot teach “skills.” We can teach knowledge but skill must be developed through practice. We can coach for skill, and we can model skillful performance, but we cannot teach skill. When we teach phonics we are teaching a body of knowledge about sight-sound correspondences, not decoding skill. The latter can only be developed through practice.

Establishing a “scientific, evidence-based” approach to reading instruction requires that we first have a good understanding of the phenomenon we call “reading.” As far as I can see, this is still a work in progress for the field of reading.

It seems like others may be as confused as I am about just what the components of reading are. Both the U.S. Dept. of Education and National Institute For Literacy at one time or another have told us that there are five components of reading: phonemics, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension. This is one reason I was surprised by the research on the components of reading and their relationships to the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) scores. In that research it said that the reading components assessed included spelling, which was measured by “A list of 15 words dictated in isolation, with an exemplar sentence for each word.”

I was also surprised to find short term memory for numbers included as one of the components of reading. Short term memory is involved in all active information processing. If so, then it is involved in reading – but is it a component of reading?

Many things are related to reading, motivation, etc. This raises to me the distinction between things that are correlated and things that are made up of components. For instance, a picture puzzle is made-up of the many pieces that are components of the picture. They are not generally thought of as correlated with the picture, but rather as part of (i.e., a component of) the picture.

It can be shown that age and reading ability are positively correlated, e.g., babies, toddlers, can’t read, children in school gradually read better and better. But I don’t think it is useful to consider age a component of reading, rather it is a correlate of reading.

It is not surprising to me that with so much confusion about what the components of reading are that people don’t always talk the same way about what we call reading nor do they all try to teach it the same way. This raises the question: What are the components of reading?

Critiquing Constructs of Intelligence and Literacy

Definitions of literacy pose problems for assessment and instruction. For instance, the Centre for Literacy in Montreal, Quebec provided the following definition of literacy: “Literacy is a complex set of abilities needed to understand and use the dominant symbol systems of a culture – alphabets, numbers, visual icons – for personal and community development. The nature of these abilities, and the demand for them, vary from one context to another. …In a technological society, literacy extends beyond the functional skills of reading, writing, speaking and listening to include multiple literacies such as visual, media and information literacy. These new literacies focus on an individual’s capacity to use and make critical judgments about the information they encounter on a daily basis.”

In contrast, the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS), the Adult Literacy and Lifeskills (ALL) survey, the National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS), the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), and the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) all defined literacy as: Using printed and written information to function in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential. These surveys go on to define: Prose literacy as the knowledge and skills needed to perform prose tasks (i.e., to search, comprehend, and use information from continuous texts); and Document literacy as the knowledge and skills needed to perform document tasks (i.e., to search, comprehend, and use information from non-continuous texts in various formats).

The adult literacy surveys focus on the performance of tasks that go from simple to more complex resulting in a scale of difficulty from easier to more difficult. The survey test development methodology is based on a theory about the components of literacy task performance that makes the tasks increase in difficulty. This set of components was validated by including them in multiple regression formulas for predicting performance on the survey tests using a response probability (RP) for getting the task correct of .80 as their criterion. But additional research showed that if the RP was dropped to .50 or below, then the components predicting difficulty changed. For instance, when predicting performance using the .80 RP a readability formula was not a useful component for predicting test performance. But when the .50 RP was used, the readability formula was a significant predictor of performance. This change resulted just by changing the RP standard, with no specified change in the theory of literacy purporting to underpin literacy task performance. This raises the question of just what it is that the tests are assessing.

Somewhat surprisingly, despite the fact that the definitions of both prose and document scales define them as the knowledge and skills needed to perform the literacy tasks, none of the adult literacy surveys actually assess and report on knowledge. This is troubling because psychometric research on intelligence over the last half century has resulted in a trend to draw a distinction between the knowledge aspect and the processing skills aspects of intelligence. Beginning in the 1940s and continuing up to the 1990s, the British psychologist, Raymond B. Cattell and various collaborators, and later many independent investigators, made the distinction between “fluid intelligence” and “crystallized intelligence.” Cattell (1983) states, “Fluid intelligence is involved in tests that have very little cultural content, whereas crystallized intelligence loads abilities that have obviously been acquired, such as verbal and numerical ability, mechanical aptitude, social skills, and so on. The age curve of these two abilities is quite different. They both increase up to the age of about 15 or 16, and slightly thereafter, to the early 20s perhaps. But thereafter fluid intelligence steadily declines whereas crystallized intelligence stays high” (p. 23).

Cognitive psychologists have re-framed the “fluid” and “crystallized” aspects of cognition into a model of a human cognitive system made-up of a long term memory which constitutes a knowledge base (“crystallized intelligence”) for the person, a working memory which engages various processes (“fluid intelligence”) that are going on at a given time using information picked-up from both the long term memory’s knowledge base and a sensory system that picks-up information from the external world that the person is in. Today, over thirty years of research has validated the usefulness of this simple three-part model (long term memory, working memory, sensory system) as a heuristic tool for thinking about human cognition (Healy & McNamara, 1996).

The model is important because it helps to develop a theory of literacy as information processing skills (reading as decoding printed to spoken language) and comprehension (using the knowledge base to create meaning) that can inform the development of new knowledge-based assessment tools and new approaches to adult education.

All the adult literacy surveys listed above used “real world” tasks to assess literacy ability across the life span from 16 to 65 and beyond. Such test items are complex information processing tasks that engage unknown mixtures of knowledge and processes. For this reason it is not clear what they assess or what their instructional implications are

(Venezky, 1992, p.4).

Sticht, Hofstetter, & Hofstetter (1996) used the simple model of the human cognitive system given above to analyze performance on the NALS. It was concluded that the NALS places large demands on working memory processes (“fluid intelligence”). The decline in fluid intelligence is what may account for some of the large declines in performance by older adults on the NALS and similar tests. To test this hypothesis, an assessment of knowledge (“crystallized intelligence”) was developed and used to assess adult’s cultural knowledge of vocabulary, authors, magazines and famous people. The knowledge test was administered by telephone and each item was separate and required only a “yes” or “no” answer, keeping the load on working memory (“fluid intelligence”) very low.

Both the telephone-based knowledge test scores and NALS door-to-door survey test scores were transformed to standard scores with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. The results showed clearly that younger adults did better on the NALS with its heavy emphasis on working memory processes (“fluid literacy”) and older adults did better than younger adults on the knowledge base (“crystallized literacy”) assessment that was given by telephone.

Consistent with the foregoing theorizing and empirical demonstration, Tamassia, Lennon, Yamamoto, & Kirsch (2007) report data from a survey of the literacy skills of adults in the Adult Education and Literacy System (AELS) of the United States. Once again they found that performance on the literacy tasks declined with increased age, that is, the higher the age of the adults, the lower their test scores became. They state that, “.the negative relationship between age and performance is consistent with findings from previous studies of adults (i.e., IALS, ALL, and NAAL; NCES 2005; OECD and Statistics Canada 2000, 2005).” They go on to say, “Explanations of these previous findings have included (a) the effects of aging on the cognitive performance of older adults, (b) younger adults having received more recent and extended schooling, and (c) the finding that fluid intelligence may decrease with age causing older adults to have more difficulties in dealing with complex” (p. 107).

Strucker, Yamamoto, & Kirsch (2005) assessed short term, working memory for a sample of adults who also completed Prose and Document literacy tasks from the IALS. They found a positive relationship between performance on the working memory task and the literacy tasks, showing that adults with better short term memories processes performed better on the IALS. Again, this is consistent with the idea that the literacy tasks involve a complex set of skills and knowledge, including the capacity to manage information well in working memory or “fluid literacy.”

Given the differences between younger and older adults on “fluid literacy” and “crystallized literacy” there is reason to question the validity of using “real world” tasks like those on the Prose, Document and Quantitative scales of the IALS, ALL, NALS, and NAAL to represent the literacy abilities of adults across the life span. In general, when assessing the literacy of adults, it seems wise to keep in mind the differences between short term, working memory or “fluid” aspects of literacy, such as fluency in reading with its emphasis upon efficiency of processing, and the “crystallized” or long term memory, knowledge aspects of reading.

It is also important to keep in mind these differences between fluid and crystallized literacy in teaching and learning. While it is possible to teach knowledge, such as vocabulary, facts, principles, concepts, and rules (e.g., Marzano, 2004), it is not possible to directly teach fluid processing. Fluidity of information processing, such as fluency in reading, cannot be directly taught. Rather, it must be developed through extensive, practice. Though I know of no research on this theoretical framework regarding the differences between fluid and crystallized literacy and instructional practices in adult literacy programs, it can be hypothesized that all learners are likely to make much faster improvements in crystallized literacy than in fluid literacy, and this should be especially true for older learners, say those over 45 to 50 years of age.

The “Skills” Versus “Knowledge” Debate and Adult Literacy Education

The decades old debate about “phonics” [ synthetic, decoding emphasis] versus “whole language” [analytic, meaning emphasis] still rages in education circles. Now this debate appears to be being joined by another debate, “skills” versus “knowledge”.

On the “skills” side of the debate, the BBC News education service reported on April 11, 2006 that the Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL) said: “The national curriculum should be fundamentally reformed with more focus on skills than specific subjects.” The Association “wants ministers to give children “entitlements” to broad skills, such as creativity and physical co-ordination, rather than specific knowledge.” The ATL general secretary Mary Bousted reportedly said at a conference, “skills” were needed, rather than knowledge on its own. Subjects could be used to “illustrate” them.”

On the “knowledge” side of the debate I found it ironically amusing that the day before the BBC news article appeared, I received my copy of The American Educator, a magazine published by the American Federation of Teachers. The Spring 2006 issue presents a lengthy series of articles and sidebars arguing against the position taken by the U.K teachers association and stating that in the U. S. schools there needs to be less of a focus on broad general skills and a much larger focus on subject matter knowledge.

The American Educator Spring issue lead in was an article by E. D. Hirsch Jr, a major commentator on education the U. S. The old adage: “You’ve got to know something to learn something” provides a succinct summary of the gist of E. D. Hirsch Jr’s article. In his article, and a recent book (Hirsch, 2006) he presents an extensive review of research that demonstrates that approaches to the teaching of reading with underachieving students that focus on “skills” or “strategies’ while largely ignoring the importance of content knowledge are likely to produce students with good decoding skills, but with poor comprehension ability. The reason is that for the most part students who lack vocabulary and comprehension of various bodies of knowledge when these are assessed by listening before the students start school, are the ones most likely to have poor comprehension skills after they learn to decode the written language. This is extensively documented in Sticht et al. (1974) which Hirsch cites in his new book to support his argument for the importance of content knowledge in reading comprehension.

Knowledge Development in Adult Literacy Education

While the “skills” versus “knowledge” debate addressed above aims at children’s education, the role of knowledge in reading is even more important for adult literacy education, where the time for developing “broad general skills” is typically very limited. The role of relevant background knowledge for adult literacy education was illustrated in research colleagues and I did to develop a 45 hour reading program for the U. S. Navy. In this work special readability formulas were developed to determine how much general reading ability, as measured by a standardized reading test, was needed to comprehend written materials about the Navy with 70 percent accuracy. We found that as background knowledge about the Navy increased from very little to a lot, the general reading ability needed to comprehend with 70 percent accuracy fell from the 11th grade to the 6th grade. In this case, high knowledge relative to what was being read was as effective as 5 grade levels of general reading ability in influencing reading comprehension.

In additional work for the Navy, we applied the findings of the importance of relevant background knowledge and developed a 45 hour reading program that used navy related content in which to embed reading skills instruction. We then compared a general reading program the Navy had which used a variety of general reading materials to the Navy-related program that used Navy-related materials. We developed and administered a Navy Knowledge test, in which students read and answered questions dealing with Navy-related knowledge but with no passages to read on the test. We also administered a reading test in which students answered questions by reading paragraphs about the Navy with the information they needed to correctly answer the questions. Additionally, a standardized reading test that provided grade level scores in general reading was administered to all students.

When compared to the general reading program that used general, civilian school-related materials, the Navy-related program made greater improvements in both Navy-related knowledge and Navy-related functional reading than did the conventional, non-job-related program. The lowest reading ability personnel (6th grade or below) in the Navy job-related program also made considerable improvements in general reading. The general reading program made more improvement on the general reading test for personnel across the reading skills spectrum, but that skill did not transfer to the performance of the Navy-related material, which is the material that the Navy personnel had to read for job advancement.

For adults in basic skills programs who generally have little time to devote to improving their reading, it is important to develop their reading skills using as the vehicle for instruction the content knowledge in which they are most immediately in need. Developing a fair amount of knowledge in some specific area, such as health knowledge, computer knowledge, consumer knowledge, job knowledge, etc., can often be done in a relatively brief period of time when the instruction is well focused on the content to be taught. With continued practice in reading in a wide range of materials, adults can develop into more generally knowledgeable and skilled literate adults.

Confusing Ignorance With Illiteracy

One of the major purposes of having people learn to read is so that they may be able to increase their knowledge about a subject. For instance, if you want to find out what someone knows about a subject, you might give them a simple multiple choice test in a written format, and then ask questions about the subject matter of interest. But this confounds the assessment of the person’s knowledge about the subject with their ability to read.

Often in what are called reading tests, knowledge and reading skill are confounded. For instance, in a vocabulary test, it may be unclear whether a person does not know the meaning of a word, or the person lacks the word recognition skill to decode the word.

In the National Assessments of Educational Progress (NAEP), reading skills and knowledge assessment are confounded in tests of science, mathematics, or other content areas because the latter assessments are given largely using the printed language and require good reading skills which some students may not have. Generally there is no attempt to separately determine a student’s knowledge in the content area separately from the person’s ability to read in the content area in an unskilled or skilled manner.

In work for the U.S. Navy, colleagues and I developed a 45 hour reading development program to help sailors improve their reading ability while increasing their knowledge needed for upward mobility in their career progression. In this program, reading instruction was integrated with Navy career progression knowledge. In assessing learning outcomes in this course we considered both improvements in Navy career progression knowledge and increases in reading skill. We did this by developing two separate assessments.

The Navy Knowledge assessment presented questions about the career progression information taught in the course and required the personnel to answer the questions drawing upon the knowledge they had in their long term memories. The Navy Functional Reading assessment presented questions for answering, along with paragraphs of written information that contained the answers to the questions. The idea here was to find out how well the personnel could read the written language to increment whatever internal knowledge they had in long term memory stored in their brains, by extracting it from the external “long term memory” formed by the written passages. By comparing the Navy Knowledge and Navy Functional Reading assessment results in pre-and post-program assessments we could determine separately the extent to which personnel had increased their Navy knowledge as well as their reading skill for incrementing their long term knowledge store using an external knowledge store.

In additional work for the U.S. Navy we developed separate readability formula for determining how much general reading ability as measured by a standardized, normed reading test a person needed to be able to comprehend Navy material with 70% accuracy. We developed formulas for four groups with high to low prior knowledge about the Navy. We found that with low background Navy knowledge a person needed a general reading ability of about the eleventh grade to comprehend with 70 percent accuracy. But highly knowledgeable personnel needed only a sixth grade level of general reading to comprehend Navy-related material with 70 percent accuracy. In this case, then, high levels of background knowledge substituted for some five grade levels of general reading ability.

The Armed Services have long understood the difference between general reading ability and specialized bodies of knowledge in developing their Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB). This assessment battery assesses both general reading vocabulary and paragraph comprehension, but also includes assessments of specialized bodies of knowledge such as Auto and Shop, General Science, Electricity and Electronics, and others. When selecting people for service, lower general reading ability scores may be offset by higher scores in specialized bodies of knowledge.

The failure to attend to differences in knowledge and literacy is a problem for the National Assessments of Educational Progress and the National Assessment of Adult Literacy. It contributes to a serious underestimation of the intellectual abilities of America’s children, youth, and adults, and it leads to the egregious error of confusing ignorance with illiteracy.

Theoretically You Can’t Teach Adults to Read and Write: But Just Keep On Doing It

Why is it so hard to get funding for adult literacy education? Innumerable studies, reports, TV shows, and statistical surveys in most of the industrialized nations of the world declare that their nation is being brought to its economic knees because of widespread low basic skills (literacy, numeracy) amongst the adult population. But repeated calls for funding commensurate with the size of the problem go unanswered. Why?

Beneath the popular pronouncements of educators, industry leaders, and government officials about the importance of adult basic skills development there flows an undercurrent of disbelief about the abilities of illiterates or the poorly literate to ever improve much above their present learning.

This was encountered close to a hundred years ago when Cora Wilson Stewart started the Moonlight Schools of Kentucky in 1911. Her claim that adults could learn to read and write met with skepticism. As she reported, “Some educators, however, declared preposterous the claims we made that grown people were learning to read and write. It was contrary to the principles of psychology, they said.”

Today that undercurrent of disbelief still flows, but today it carries with it the flotsam and jetsam of “scientific facts” from genetics science, brain science, and psychological science. Look here at objects snatched from the undercurrent of disbelief stretching back for just a decade and a half.

2006. Ann Coulter is a major voice in the conservative political arena. In her new book, Godless: The Church of Liberalism (Chapter 7 The Left’s War on Science: Burning Books to Advance “Science” pages 172-174) she clearly defends the ideas given in Murray & Herrnstein’s book The Bell Curve regarding the genetic basis of intelligence. By extension, since The Bell Curve uses reading and math tests in the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT), Coulter is discussing the genetic basis of literacy and numeracy.

In her book she says about The Bell Curve book: “Contrary to the party line denying that such a thing as IQ existed, the book methodically demonstrated that IQ exists, it is easily measured, it is heritable, and it is extremely important. …Among many other things, IQ is a better predictor than socioeconomic status of poverty, unemployment, criminality, divorce, single motherhood, workplace injuries, and high school dropout rates. …Although other factors influence IQ, such as a good environment and nutrition, The Bell Curve authors estimated that IQ was about 40 to 80 percent genetic.” (p. 173)

Coulter goes on to discuss the misuse of science in the same chapter in relation to AIDS and homosexuality, feminism, trial-lawyers law suits, DDT and environmentalists, abortion and stem cell research, and other topics that are controversial among large segments of the population but of mainstream concern in the far right conservative base in the United States.

Because of her position as a best-selling author and spokesperson for conservative groups, Ann Coulter’s ideas about the genetic basis of intelligence and high school dropouts can have a profound impact upon political thinking about basic skills education among adults who have not achieved well.

2005. The Nobel Prize winning economist James J. Heckman in an interview at the Federal Reserve Bank region in Chicago discussed his ideas about cognitive skills and their malleability in later life with members of a presidential commission consisting of former U.S. senators, heads of federal agencies, tax attorneys and academic economists. Later in his interview he discusses what Adam Smith, in his The Wealth of Nations said and why he, Heckman, disagrees with Smith.

According to Heckman, Adam Smith said, “… people are basically born the same and at age 8 one can’t really see much difference among them. But then starting at age 8, 9, 10, they pursue different fields, they specialize and they diverge. In his mind, the butcher and the lawyer and the journalist and the professor and the mechanic, all are basically the same person at age 8.”

Heckman disagrees with this and says: “This is wrong. IQ is basically formed by age 8, and there are huge differences in IQ among people. Smith was right that people specialize after 8, but they started specializing before 8. On the early formation of human skill, I think Smith was wrong, although he was right about many other things. … I think these observations on human skill formation are exactly why the job training programs aren’t working in the United States and why many remediation programs directed toward disadvantaged young adults are so ineffective. And that’s why the distinction between cognitive and noncognitive skill is so important, because a lot of the problem with children from disadvantaged homes is their values, attitudes and motivations.…Cognitive skills such as IQ can’t really be changed much after ages 8 to 10. But with noncognitive skills there’s much more malleability. That’s the point I was making earlier when talking about the prefrontal cortex. It remains fluid and adaptable until the early 20s. That’s why adolescent mentoring programs are as effective as they are. Take a 13-year-old. You’re not going to raise the IQ of a 13-year-old, but you can talk the 13-year-old out of dropping out of school. Up to a point you can provide surrogate parenting.”

Here Heckman seems to think of the IQ as something relatively fixed at an early age and not likely to be changed later in life. But if IQ is measured in The Bell Curve, a book in which Heckman found some merit, using the AFQT, which in turn is a literacy and numeracy test, then this would imply that Heckman thinks the latter may not be very malleable in later life. This seems consistent with his belief that remediation programs for adults are ineffective and do not make very wise investments.

2000. It is easy to slip from talking about adults with low literacy ability to talking about adults with low intelligence. On October 2, 2000, Dan Seligman, columnist at Forbes magazine, wrote about the findings of the National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS) of 1993 and said, “But note that what’s being measured here is not what you’ve been thinking all your life as “literacy. ” The cluster of abilities being examined is obviously a proxy for plain old “intelligence.” He then goes on to argue that government programs won’t do much about this problem of low intelligence, and, by extension, of low literacy.

These types of popular press articles can stymie funding for adult literacy education. That is one reason why it is critical that when national assessments of cognitive skills, including literacy, are administered, we need to be certain about just what it is we are measuring. Unfortunately, that is not the case with the 1993 NALS or the more recent 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). These assessments leave open the possibility of being called “intelligence” tests leading some, like Seligman, to the general conclusion that the less literate are simply the less intelligent and society might as well cast them off – their “intelligence genes” will not permit them to ever reach Level 3 or any other levels at the high end of cognitive tests.